209. The Modern Emergency Docket Turns Ten

The Supreme Court's February 2016 rulings blocking President Obama's Clean Power Plan were unprecedented at the time; in retrospect, they were harbingers of a deep paradigm shift in the Court's role.

Welcome back to “One First,” a newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to lawyers and non-lawyers alike. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current issues, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

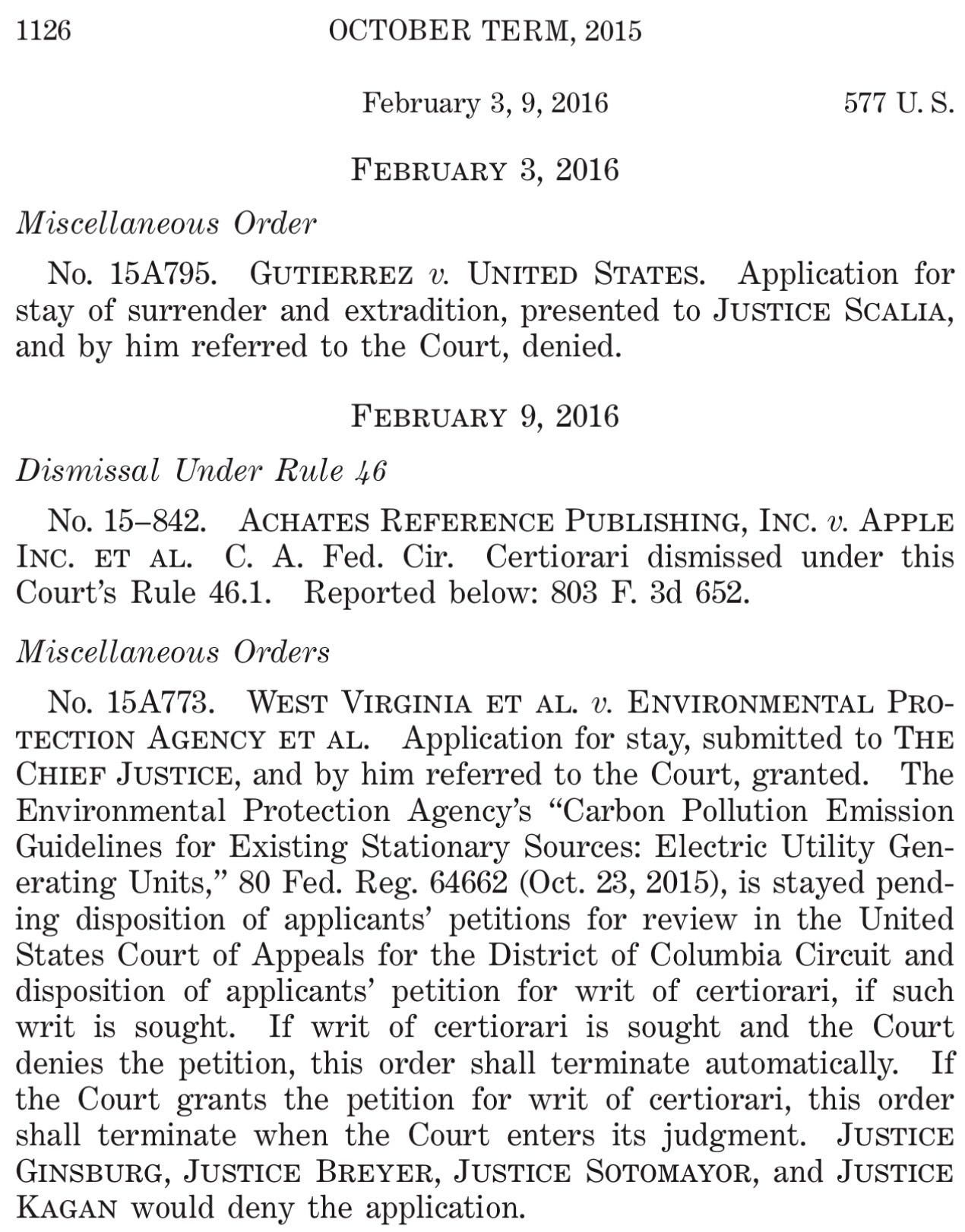

I wanted to use today’s “Long Read” to take a step back from all of the news of the moment (some of which I covered on Saturday), and reflect on a fairly significant anniversary that hits today—the tenth anniversary of the Court’s five rulings on February 9, 2016, in which a 5-4 majority granted emergency relief to block President Obama’s “Clean Power Plan.” The orders, one of which is pictured below, were unsigned and entirely unexplained. And they were also, at least at that point, completely unheard of. As Justice Kagan would note in 2022, “Never before had the Court stayed a regulation then under review in the lower courts.”

In retrospect, the Court’s interventions on February 9, 2016 were the birth of what we might call the modern emergency docket (or whatever you want to call it). Although the justices had regularly entertained (and sometimes granted) applications for emergency relief in death penalty and election cases in the years leading up to 2016, there are virtually no examples of full Court emergency relief respecting national (or even non-election-related state) policies prior to the Clean Power Plan orders. Indeed, the Court’s norm for decades had been to have emergency applications resolved only by individual justices—not by the full Court—at least in part to moderate the effects of any rulings. And yet, within 18 months of the Clean Power Plan rulings, the Court was regularly receiving applications from (and granting emergency relief to) the first Trump administration—rulings that, following the precedents the Court set in the Clean Power Plan cases, were unsigned and entirely unexplained.

Other than Justice Kagan’s cryptic reference in her 2022 dissent in West Virginia v. EPA, there’s been virtually no public accounting of why the Court intervened when it did, or what led the five justices in the majority to agree to a procedural move the Court had never undertaken before. But what can’t be gainsaid is that the ruling was the progenitor of a much broader—and more problematic—pattern of behavior by the Court, one that, as the last year has underscored, has become an ever-more-significant feature of the Court’s work, and an ever-more-controversial one, to boot.

More on all of that below. But first, the news.

On the Docket

The only ruling of any kind out of the Court last week was Wednesday’s denial of California Republicans’ emergency application that had asked the justices to block California’s (Texas-motivated) congressional redistricting. As I suggested last week, there was no universe in which the Court could remotely justify intervening to block California’s map given the terms on which it had intervened in December to un-block Texas’s map. The fact that there were no public dissents may suggest that the justices all agreed.

It also seems worth pointing out that the summary denial is a pretty big slap in the face to the Trump administration, and Solicitor General Sauer, specifically—who had filed a brief urging the Court to block California’s map, never mind that he had also filed a brief in the Texas case urging the Court to stay a district court decision that had found the exact same equal protection violation in Texas that Sauer claimed occurred in California. I suspect that the federal government’s hard-to-defend hypocrisy was not lost on the justices; whether it leads to any broader erosion of the SG’s credibility before the Court remains to be seen.

Turning to this week, there is, again, nothing scheduled from the Court. We don’t expect any rulings in argued cases or even any regular orders. It’s possible there will be movement on some non-Trump-related emergency applications (and also possible that we get a new application for emergency relief from DOJ in seeking to block last week’s district court ruling that kept in place “temporary protected status” for more than 350,000 Haitians—at least, if the Trump administration wants to move faster than the deliberate timeline the D.C. Circuit has set for resolving its stay request there).1 But it’s also possible the week comes and goes with no news out of the Court whatsoever.

Finally, in the (completely) miscellaneous category, the Court last week posted its official calendar for the October 2026 Term. Near as I can tell, there are no obvious structural changes from this term, but for those who set their watches by the Court’s calendar, you can now plan all the way to June 2027.

The One First “Long Read”:

The Court Enters Its Emergency Docket Era

The Clean Power Plan

The Clean Power Plan (CPP) was an Obama administration policy aimed at attempting to slow the rate of climate change, which was first proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in June 2014, and became a final rule in October 2015. Under the CPP, each state was assigned a target for reducing carbon emissions within its borders, which could be accomplished through a range of possible alternatives that were up to the states to choose—but with the specter of EPA intervention if a state refused to submit a conforming plan. One of the core concepts of the CPP was that states would shift electricity generation away from fossil fuel-fired power plants to other sources of energy. Indeed, the CPP aspired to reduce carbon emissions from electricity generation by the year 2030 by 32 percent relative to those levels in 2005—and aspired to reduce other harmful air pollution as well.

Once it was finalized, the CPP was immediately challenged in court by a slew of power-generating companies and (mostly Republican) state attorneys general—who brought 39 petitions for review in total. By statute, those challenges had to be brought in the first instance in the D.C. Circuit federal appeals court, where they were consolidated. And shortly after filing their challenge, the petitioners in the cases asked the court of appeals for emergency relief—to “stay” the CPP under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) for the duration of the litigation. In an unsigned order on January 21, 2016, a three-judge D.C. Circuit panel (Henderson, Rogers, & Srinivasan, JJ.) denied the applications for a stay—but agreed to expedite its review of the CPP’s statutory validity under section 111 of the Clean Air Act, setting oral argument for June 2, 2016 (and leaving the parties to work out a remarkably compressed briefing schedule in the interim).

On January 26, 2016, five applications for a “stay” of the CPP were filed in the Supreme Court. At the heart of the applications were two arguments beyond the “merits” (i.e., that the CPP exceeded the EPA’s authority under section 111 of the Clean Air Act): First, that immediate relief was necessary to prevent the EPA from effectively forcing the states to comply with the CPP even if it was later struck down (a charge the applicants leveled at the EPA’s behavior after the Court’s 2014 ruling in Michigan v. EPA); and second, that even though the CPP’s targets were 14 years in the offing (and no state plans were due until September 2018), the mere existence of the plan was “forcing States to expend money and resources, displacing the States’ ability to achieve their own sovereign priorities, and requiring some States to change their laws to enable or accommodate a ‘shift’ from fossil fuel-fired generation to other sources of energy.”

Even though the Solicitor General pointed out, in his response, that expedited review in the D.C. Circuit would still allow for a decision before those harms became substantial, and that the Supreme Court had never before issued a “stay” of an entire federal regulation, the Court acquiesced—granting stays in all five cases, with no explanations, on February 9, 2016. The rulings were all 5-4, with Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan noting their dissents. Indeed, the five rulings on February 9 would be the last five rulings in which Justice Scalia publicly voted before he died, four days later (more on this in the trivia, below).

The Precedent the Court Set

The Court’s ruling was a bombshell. By the end of the day on February 9, the New York Times was pointing out what Justice Kagan would reiterate later—that “the Supreme Court had never before granted a request to halt a regulation before review by a federal appeals court.” Indeed, a “stay” of “administrative action” doesn’t make much analytical sense; in the typical case, a stay is directed toward a prior ruling by that court or a lower court, and has the effect of suspending its effects. The relief the applicants were seeking in the Clean Power Plan cases was to block the EPA (an executive branch agency) from continuing to enforce the CPP—relief against the executive branch that certainly has the feel more of an injunction than a stay. (More on this, too, in a moment.) But the nomenclature aside, the larger point was that the Court just … hadn’t been in the business of blocking federal policies on a nationwide basis at the outset of litigation; one was hard-pressed to find examples of rulings even blocking state policies in that context. As I’ve explained in detail, into the mid-2010s, the bulk of the Court’s emergency docket was composed of death penalty and election-related applications, not “can the government continue to enforce this policy or not”?

Of course, the justices may have had good reasons for intervening. But just as significant as the fact that the Court intervened was the way in which it did so—without writing a word about why. Just two weeks after the first applications had been filed, just four days after the briefing was complete (two of which were a weekend), and with no briefs from other interested (or disinterested) parties or oral argument, the Court blocked—at least temporarily—the Obama administration’s signature environmental policy, and didn’t seem inclined to provide even an iota of explanation as to what justified such an unprecedented intervention.

At least as the Obama administration had formulated it, the Clean Power Plan never made it back to the Supreme Court. The first Trump administration effectively repealed it. And in 2022, the Supreme Court, in a case raising all kinds of justiciability issues, held that the EPA lacked the statutory authority on which the CPP had been based—by concluding that the EPA’s authority to identify the “best system of emission reduction” under section 111 of the Clean Air Act did not allow it to create emissions caps (that decision reflected the birth, at least in crystallized form, of the so-called “major questions doctrine”). Had the CPP still been on the books, that ruling (which, like the lead Clean Power Plan case, was captioned West Virginia v. EPA) would have killed it.

***

Besides the specific precedent it helped to set with respect to the CPP and section 111 of the Clean Air Act, the February 2016 rulings in the Clean Power Plan cases created broader precedents in at least three respects—all of which have helped to profoundly reshape the timing, structure, and nature of the Supreme Court’s work.

First, the CPP rulings created a brand-new precedent for the Court to issue “stays” of administrative action by the executive branch through emergency applications—effectively allowing the justices to go “first” in some remarkably high-profile cases. Two other high-profile examples—where the Court granted emergency relief in the form of a “stay” of a nationwide regulation when the only lower-court ruling was a circuit-level decision denying the same—came in the COVID eviction moratorium and OSHA vaccination-or-testing mandate cases. It’s not at all obvious either (1) from where the Court derives the authority to issue such a “stay” (rather than an injunction); or (2) why the standard of review in such cases is the traditional balancing test for stays pending appeal, rather than the more rigorous standard for an injunction pending appeal. In other words, calling the relief the parties had sought in the Clean Power Plan cases a “stay” necessarily allowed the Court to grant their request without meeting the even-higher bar usually required to freeze executive action in that posture. (There’s an excellent 2024 Harvard Law Review student note that examines this puzzle in far more detail.) The doctrinal mush aside, what no one can dispute is that the Clean Power Plan rulings were the foundation for the ones that came later.

Second, and the specific type of emergency relief aside, the Clean Power Plan rulings were also the beginning of a much broader trend—in which the justices quickly became comfortable intervening with nationwide (or statewide) consequences at the beginning of litigation in far more cases. I wrote about all of the examples of this behavior, which only accelerated after the February 2016 rulings, in my 2024 law review article, “A Court of First View.” Suffice it to say, there are a host of reasons beyond the formalities discussed above why the justices usually insist that they don’t like deciding important questions of federal law before they’ve had a chance to fully develop (and “percolate”) in the lower courts. And although there are scattershot pre-2016 examples of the full Court staying lower-court injunctions or granting their own injunctions pending appeal, they were remarkably few and far between (and usually quite narrow); the Clean Power Plan rulings may well have helped to open the floodgates. After all, just like in the OSHA vaccination-or-testing mandate case, the only ruling by any court prior to the Supreme Court’s intervention in the Clean Power Plan cases had been the D.C. Circuit’s cryptic denial of the petitioners’ application for a stay. For a Court that, under both the Constitution and its own settled precedents, is supposed to exercise only “appellate” jurisdiction in such cases, it’s quite a shift to have it deciding such weighty legal and public policy questions issues on no record and with no meaningful prior involvement by the lower courts.

Third, to whatever extent the justices in the majority in the Clean Power Plan cases had case-specific justifications for why they chose to intervene—(explanations that might have stemmed that tide of the broader interventions to come), they also set a fairly significant precedent by not sharing those justifications with us. Even though time was hardly of the essence, and it should have been easy enough to write … something, the Court rushed out summary orders four days after the applications were fully briefed without a word of explanation—from either the majority or the dissenters. It’s possible that everyone thought the intervention was temporary, and that there’d be a full opportunity to flesh out the details when (not if) those cases came back. But Justice Scalia died four days later (which, among lots of other things, threw the Court’s docket into a bit of chaos); and the results of the 2016 election ensured that the litigation the Court might have contemplated in February took an entirely different form by November. Either way, because the Court didn’t write then, and hasn’t explained itself since, we’ll never know (at least, until our grandkids can read the justices’ internal papers from that time period). In the interim, any case-specific justifications for intervening in the Clean Power Plan cases have been swallowed by the Court’s willingness to intervene at the emergency application stage in countless other contexts in the ten years since—interventions that continue to come without much (if anything) in the way of reasoned explanations.

Beyond setting those precedents, the fact that we’ve reached the tenth anniversary of this behavior from the Court ought to matter in one last respect: I’ve often been on panels or in conversations in which those more inclined to reflexively defend the Court have suggested that the surge of emergency applications from the Trump administration over the past year is a new phenomenon, and that the justices should be given some time to “figure out” how to handle them. I certainly agree that the volume we’ve seen over the past year is unprecedented. But the Court’s own behavior respecting emergency applications is, at this point, too deeply entrenched and too well-developed to be dismissed as a knee-jerk response to a brand-new problem. Reasonable people can disagree about what the best practices are and ought to be for how the current Court is going to deal with the new normal of requests for emergency relief. What can no longer be denied at this point by anyone who’s paying attention is that the new normal has been “normal” for long enough that we ought to have some answers by now.

SCOTUS Trivia: Justice Scalia’s “Lasts”

As noted above, the five orders in the Clean Power Plan cases were the last publicly discernible votes taken by Justice Scalia before his death on February 13, 2016. But there are a few other interesting “lasts” to mark the end of one of the more significant tenures of any justice appointed to the Court in my lifetime (so, from O’Connor onwards).

First, Justice Scalia’s last majority opinion was filed on January 20, 2016, in Kansas v. Carr, where, for an 8-1 majority, he wrote that, in capital cases, the trial court does not need to instruct a jury that mitigating circumstances need not be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. (Sorry for the double-negative, but it only makes analytical sense when framed that way.) In other words, a capital sentence isn’t vulnerable just because the jury might have thought mitigation did have to be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. (Justice Sotomayor dissented.)

Second, the last oral argument in which Justice Scalia participated was also on January 20—in Sturgeon v. Frost, a case in which a unanimous Court would eventually side with an Alaskan fisherman in a dispute over whether he could use a hovercraft on a stretch of a river that flowed through a federal wildlife preserve.

Third, Justice Scalia’s last opinion, period, was his January 25 dissent in Montgomery v. Louisiana, an incredibly technical but remarkably important state post-conviction case in which a 6-3 majority held not only that the Court’s 2012 decision in Miller v. Alabama was a “substantive” rule that could be enforced even by those whose convictions had become final before Miller, but that a state prisoner’s right to bring a Miller claim came from the Constitution itself—the first (and, as of this writing, only) time the Court has ever expressly held that the Constitution protects any post-conviction challenges to criminal convictions.

Finally, although the Clean Power Plan cases were Justice Scalia’s last publicly discernible public vote, the last ruling of any kind in which he participated came the day after the Clean Power Plan rulings—when the Court denied a Texas death-row prisoner’s application for a stay of execution (and petition for a writ of certiorari) over no public dissents.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one:

This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone no later than next Monday (and, if I were a betting man, sooner). As ever, please stay safe out there.

On Saturday, the D.C. Circuit motions panel to which the government’s stay application was assigned (Walker, Pan, & Garcia, JJ.) ordered the plaintiffs to respond by next Monday, and for any reply from the government to be filed by next Thursday (February 19).

I thought Montgomery v. Louisiana was 6-to-3 rather than 5-to-4? Kennedy wrote the opinion, joined by Roberts, Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan. Scalia, Thomas, and Alito dissented.

If Congress can be backed into voting for release of the Epstein files, it can be pushed into setting limits on ICE.

When public opinion is STRONG, Trump knows he has to back down. It's time to call Congress (202 224 3121) and the White House (202 456 1414) about ICE reform. The next 10 days are critical. Read about the 10 Democratic proposals to curb ICE.

https://kathleenweber.substack.com/p/the-most-important-thing-you-can