168. The Cambodia Bombing Case

The August 1973 contretemps over President Nixon's bombing of Cambodia was a turning point in how the Supreme Court handles emergency applications—and a harbinger of things to come.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); and we’ll usually have a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current issues, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

Given the rather dramatic upswell in interest in how the Supreme Court handles emergency applications, I thought I’d use today’s issue to tell (or, for those who have read The Shadow Docket, re-tell) the story of the August 1973 Cambodia bombing case—which was not just a fascinating episode in its own right, but which turned out to be a real inflection point in how the Supreme Court handles emergency applications.

As folks think about whether there’s a better way for the justices to deal with quick-hitting emergencies than the approach we’re seeing from the current Court, the Cambodia case is an especially absorbing (if extreme) example of how the Court used to handle these cases—relying on circuit justices (who would often hold “in-chambers” arguments and write “in-chambers” opinions) rather than the full Court. And the way the Court resolved the unique conflict that arose between Justices Douglas and Marshall in that case turns out to have been a harbinger for how the Court would approach emergency applications going forward—with Justice Douglas’s dissent previewing many of the objections that continue to resonate today.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

The biggest headline of the week was, obviously, Monday afternoon’s ruling granting a stay to the Trump administration in the Department of Education downsizing case—about which I wrote on Monday.

The full Court handed down only two more rulings last week—both of which denied stays of execution to Florida prisoner Michael Bell (in one case, over public dissents by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan). The only other news out of the Court last week was an administrative stay entered by Justice Kavanaugh on Wednesday—temporarily pausing a massively important Eighth Circuit ruling that held that the central provision of the Voting Rights Act can be enforced only by the federal government, and not in suits by private plaintiffs. The plaintiffs in the Eighth Circuit case have asked the Court to stay that ruling while they appeal it; Kavanaugh’s administrative stay gives the Court a bit more time to decide whether to take them up on the invitation (and may reflect at least some chance that it will).

Turning to this week, we expect the first tranche of summer housekeeping orders later this morning—none of which should be especially newsworthy. In addition to the emergency application in the Voting Rights Act case, the Court is also still sitting on an application from the Trump administration to clear the way for the President to remove members of the Consumer Product Safety Commission. And Tennessee death-row inmate Byron Lewis Black has also filed an application seeking a stay of his execution (which is currently scheduled for August 5). Rulings on any/all of those applications could certainly come this week—or not.

The One First “Long Read”:

The Origins of the Modern Emergency Docket

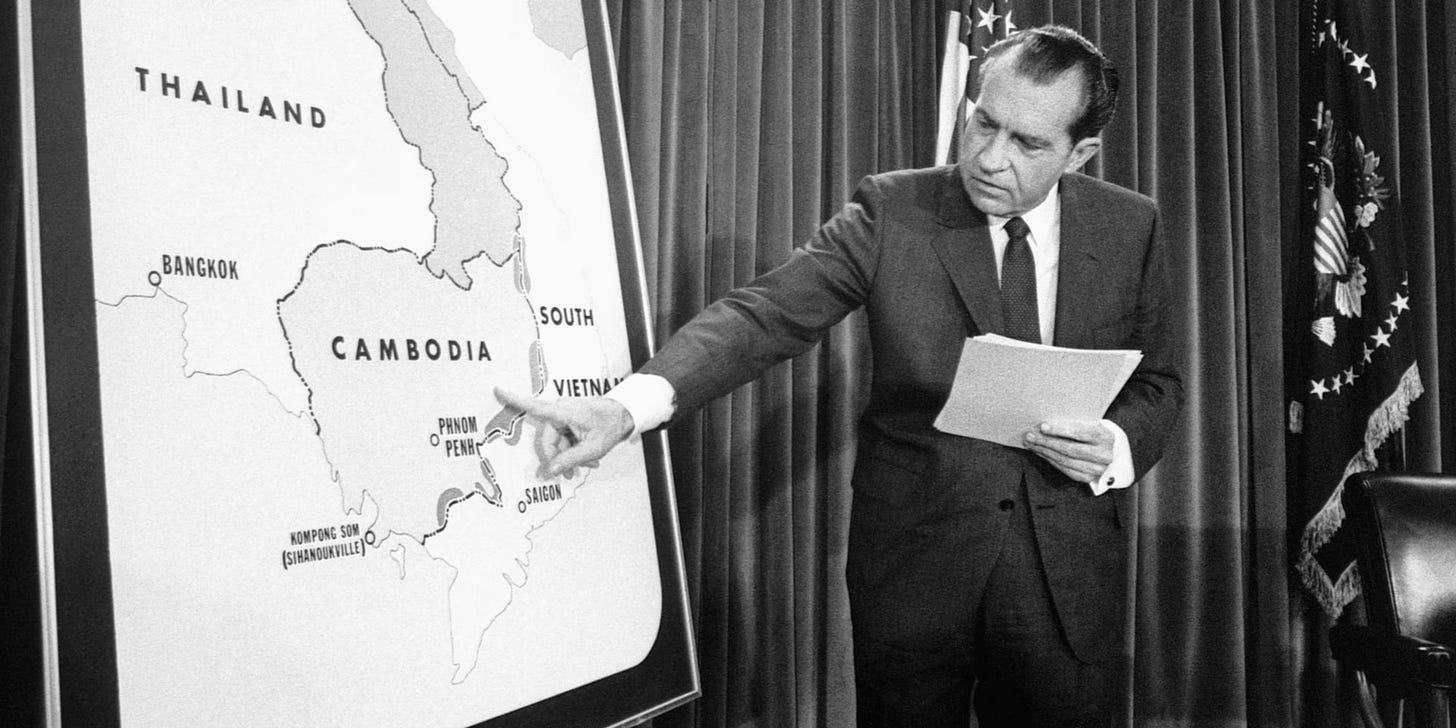

On the morning of August 2, 1973, from his summer cottage in Goose Prairie, Washington, Justice William O. Douglas set in motion one of the strangest proceedings in the history of the United States Supreme Court.1 At the urging of lawyers who had flown across the country the day before and driven through the night to reach him, Douglas agreed to convene a hearing by himself the next day at the U.S. Post Office and Courthouse in nearby Yakima. The federal building was 41 miles from Douglas’s shack in the woods, and 2700 miles away from his chambers in Washington, D.C., where such arguments would usually be held. On his own authority, from the middle of nowhere, Douglas had decided to halt President Nixon’s highly controversial, and quite possibly unlawful, bombing of Cambodia. By far the Court’s harshest critic on all things related to the war in Southeast Asia, the never-lacking-for-confidence Douglas finally had the perfect opportunity to speak his mind.

The last American troops had left Vietnam four months earlier. But amidst mounting pressure from the ongoing Watergate hearings, President Nixon had continued to bomb Communist strongholds in neighboring Cambodia. And although Congress, having long-since soured on U.S. operations in that part of the world, attempted to cut off all funding for the Cambodia operations, Nixon vetoed its first attempt to do so. Lacking the votes to override Nixon’s veto, Congress instead enacted the “Fulbright Proviso,” which again terminated funding for any military operations “in or over . . . Cambodia.” This time, though, in a bid to secure the President’s approval, Congress specified that the cut-off would apply only “on or after August 15, 1973.”

On July 1, a besieged Nixon signed the revised bill into law—and continued the bombing. After all, as government lawyers would claim, by prohibiting the bombing only as of August 15, Congress had arguably authorized it until then. Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman and a group of active-duty Air Force officers stationed in nearby Thailand disagreed. They quickly filed a lawsuit in federal court against Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, arguing that even before the August 15 cutoff, the bombing was still unlawful because it had not been specifically approved by Congress.

The lawsuit, filed in Brooklyn and assigned to Judge Orrin Judd, asked the court to enter an injunction against Schlesinger to bar the federal government from continuing with the bombing. On July 25, Judd sided with Holtzman and agreed to temporarily halt the government’s aerial campaign. His ruling was the first example in American history of a judicial injunction against an ongoing military operation.

But Judge Judd’s ruling did not have any immediate impact. Recognizing the novelty and gravity of the situation, Judd explained that his ruling would not take effect for two days. This gave the government time to seek a stay. Sure enough, the Justice Department quickly sought such relief, and the Second Circuit (the Manhattan-based federal appeals court) agreed, allowing the bombing to continue while it considered the government’s full appeal of Judge Judd’s ruling. Undeterred, Holtzman immediately appealed that ruling to the Supreme Court, asking the justices to vacate the Second Circuit’s stay. If that happened, Judge Judd’s injunction would go into effect and the bombing would be halted for however long it took the government’s appeal to be resolved.

Even the government agreed that the bombing had to end by August 15, so the clock was running. With most of the justices scattered for the summer break, there wouldn’t be time for the full Court to meet in person before there would no longer be anything left for them to decide. With only a few weeks go to until Congress’s deadline, the question before the Court was not whether the bombing was or was not legal; it was more technical: Which should go into effect—the district court’s ruling blocking the bombing, or the Second Circuit’s stay allowing it to continue?

At least initially, that question went not to Douglas, but to Justice Thurgood Marshall. The legendary civil rights lawyer, who President Johnson had appointed as the Court’s first Black justice in 1967, was the designated “Circuit Justice” automatically assigned to oversee procedural requests relating to the Manhattan-based federal appeals court. To that end, on Monday, July 30, Marshall heard several hours of argument in his wood-paneled chambers in Washington. Two days later, he filed a 12-page opinion that openly agonized over the gravity of the question before him, but ultimately refused to upset the apple cart. “I would exceed my legal authority,” Marshall wrote, “were I, acting alone,” to lift the stay. With the justices unable to convene in person, Marshall felt obliged to act not as he might have wished to, but as he thought the full Court would. Begrudgingly, Marshall sided with Nixon, and the bombing continued.

Normally, that would have been the end of the matter. But this wasn’t a normal case. Burt Neuborne, who represented the plaintiffs, flew from Washington, D.C. to Portland, Oregon the next day and drove through the night to Goose Prairie. Neuborne’s goal was to persuade Marshall’s senior colleague, the 74-year-old Douglas, to come down from the mountain and stop the bombing. It was, in Neuborne’s words, a “cross-country hail mary.”

The choice of Douglas was no accident. Appointed to the Court by Franklin Delano Roosevelt five months before World War II began in Europe, by 1973, he was the Court’s senior Associate Justice. Often referred to by his detractors as “Wild Bill,” Douglas had long since established his bona fides not only as the Court’s most ardent and doctrinaire civil libertarian, but as its loudest critic of the Vietnam War. Douglas was critical not only of the war, but of his colleagues on the Supreme Court, who had repeatedly refused to take up cases asking whether Congress had approved of the government’s substantial and sustained uses of military force in southeast Asia.

On the rare occasions in which the Court had explained its refusal to intercede, it usually identified some technical, procedural roadblock that would not allow the justices to actually resolve the legality of the war, such as whether the plaintiff was a proper party to bring the challenge or whether it was appropriate for the courts, rather than the political branches, to decide the question in the first place. Almost every time, Douglas dissented, just as he had most recently on June 21, 1973 (four days before the Court adjourned), when the justices threw out a civil suit against the Ohio National Guard arising from the Kent State massacre.

Six weeks later, here, at last, was an opportunity for the tired and irascible Douglas to rule on a piece of the war all by himself, without having to persuade any of his eight colleagues to join him. Under the Court’s esoteric rules in such cases, Neuborne couldn’t have gone directly to Douglas. But once the assigned “Circuit Justice” for the relevant lower court (Marshall) had refused to act, the rules technically allowed Neuborne to ask any other justice for the same relief. When the Court was in session, such a request would be forwarded to the full Court to prevent lawyers from trying to pick and choose justices who they thought would be more sympathetic to their case. But that wasn’t possible in early August 1973.

So it was that, on the morning of Thursday, August 2, Neuborne’s colleague Norman Siegel delivered the relevant legal papers to Douglas at his Goose Prairie home. Unshaven and in a bathrobe, Douglas responded that he would need a few hours to look over the briefs. In one especially notorious prior episode, a lawyer who had similarly hand-delivered a request returned to find Douglas’s order rejecting it nailed to a nearby tree. When Siegel returned, though, he got better news: Circuit Justice Douglas would hear oral argument on the matter the next morning in Yakima, so that the federal government could be represented as well. It wasn’t the first time that Douglas had commandeered the nearest federal courtroom, but it was certainly the most dramatic.

The unusual spectacle aside, the result of Friday’s hearing at what is now known as the William O. Douglas Federal Building was a foregone conclusion. While Neuborne flew home to New York, Douglas—using a series of roadside pay phones along his drive back up into the mountains—dictated his ruling and a brief opinion to a clerk back in D.C. When the order was formally handed down from the Supreme Court in Washington at 9:30 on Saturday morning, it lifted the Second Circuit’s stay of Judge Judd’s injunction; the bombing was to be halted. Douglas did not actually rule that the bombing was unlawful. Instead, he wrote that it was a close question, and that the stakes were too high to allow the bombing to continue until and unless courts conclusively resolved the dispute. In his words, “denial of the application before me would catapult our airmen as well as Cambodian peasants into the death zone.”

Douglas’s mandate, which the military appears to have ignored, was in any event short-lived. Rather than accepting Douglas’s ruling as the last word, the Justice Department pursued a clever procedural maneuver. Douglas’s Saturday morning order had lifted the stay that had been imposed by the Second Circuit, clearing the way for Judge Judd’s injunction halting the bombing to go back into effect. But the Supreme Court, and each of its justices by themselves, had the power under a series of old statutes to issue their own stays of trial-court rulings—regardless of what the intermediate court of appeals had done. Quickly, then, the federal government returned to Justice Marshall. This time, instead of asking Marshall to leave the Second Circuit’s stay in place (as it had five days earlier), it asked him to issue a stay of his own—to freeze Judge Judd’s injunction directly.

Just over six hours after Douglas’s order had been released, Marshall once again sided with the Nixon administration. Not only did he acquiesce in the government’s rare procedural move, but he took an unprecedented step to preempt any further maneuvering by Douglas: As his solo opinion concluded, “I have been in communication with the other Members of the Court,” and all seven of them “agree with this action.” Because Marshall was ruling in his individual capacity as Circuit Justice, he didn’t need the concurrences of the other justices. Nor could the other justices provide such concurrences, since the Court was not formally in session. But by emphasizing that he had his colleagues’ informal support, Marshall was sending an unequivocal signal to Douglas to desist. For what appears to be the first time in the Court’s history, the justices effectively voted by telephone. And they voted for 10 more days of bombing.

Douglas filed a vehement dissent. He did not doubt that the full Court had the power to overrule him; it had happened before. In June 1953, the justices had come back to the bench after recessing for the summer to hold a rare “Special Term,” entirely to rebuff Douglas’s eleventh-hour effort to block the executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the only two American civilians sentenced to death for espionage during the Cold War. But unlike in 1953, the justices had not returned to Washington to hold a public hearing and overrule Douglas in person; this time, they rebuked him privately and by telephone.

Formally, Douglas argued that Marshall’s second ruling was void, because only the full Court could supersede his ruling. Marshall may have consulted with the other justices by telephone, but because the Court wasn’t in session, he couldn’t claim a quorum; only a Special Term could accomplish that. But Douglas focused just as much on his practical objections to Marshall’s Saturday decision. As he explained, by purporting to vote by telephone, the justices had defeated the purpose of having the full Court gather in person to discuss and decide cases collectively at their Conference, a tradition dating back to the early 1800s. “A Conference brings us all together; views are exchanged; briefs are studied; oral argument by counsel for each side is customarily required,” Douglas explained. “But even without participation the Court always acts in Conference and therefore responsibly.” Moreover, Douglas wrote, it had been his experience that “profound changes are made among the Brethren once their minds are allowed to explore a problem in depth.” Here, in contrast, “there were only a few of the Brethren who saw my opinion before they took contrary action.” Such a “Gallup Poll type of inquiry of widely scattered Justices is, I think, a subversion of the regime under which I thought we lived.”

Whoever had the better arguments in the Cambodia case, no one doubted that it was a black eye for the Court. The public sniping between Marshall and Douglas painted the justices in a less-than-flattering light on a topic about which the country was already deeply divided. Worse, it made a public spectacle out of the bitter internal debate over the Court’s non-intervention in Vietnam. For lawyers, it also appeared to provide a roadmap for how future parties could shop a case around until they found a single justice willing to grant emergency relief, hardly a message that the Court wanted to send, especially so long as the increasingly unpredictable Douglas remained on the bench.

Most troubling of all, though, was the headline splashed across the front page of the New York Times on Tuesday, August 7: Less than 36 hours after the denouement in Washington, an Air Force raid in Cambodia had mistakenly bombed the town center of Neak Loeung, killing at least 137 people, most of whom were civilians, and wounding hundreds more. As Douglas had feared, the Supreme Court had indeed “catapult[ed] . . . Cambodian peasants into the death zone.” It was a stunningly immediate real-world consequence of the justices’ procedural machinations.

Neither Douglas nor his colleagues ever commented publicly on the Neak Loeung bombing. The only visible impacts the Cambodia affair had on the Court were a series of subtle but undeniable shifts in the justices’ internal procedures. Not long after the Marshall-Douglas contretemps, the justices began to take any applications seeking emergency relief from a second justice after a first had declined to intervene and refer them to the full Court, rather than ruling on them solo, even during the summer recess. The justices also normalized Marshall’s Saturday maneuver, informally taking their colleagues’ temperatures when they received any applications on which the Court might divide, and only resolving by themselves those on which there was a clear consensus. By the end of the 1970s, the Court would quietly discontinue its practice of formally “adjourning” when the justices left for the summer, so that it would be possible to issue decisions from the full Court even when some (or all) of the justices were elsewhere. (Curiously, the Court would not formalize this change in its rules, to a “continuous” Term, until 1990.) At least in those respects, the Court appeared to be reacting to the very concerns about its internal processes that Douglas had raised in the Cambodia affair.

But these technical, procedural changes did nothing to address Douglas’s substantive concerns about the danger of the full Court deciding weighty matters on an expedited basis, without detailed deliberation, multiple rounds of briefing, and oral argument. If anything, these procedural changes, which made it easier for the entire Court to resolve emergency applications without detailed briefing and in-person arguments, may have only exacerbated Douglas’s objections. After all, although Marshall and Douglas each had the benefit of detailed briefs and in-person arguments to fully flesh out their views on the questions presented in the Cambodia case, the other seven justices had not. Indeed, when they voted by telephone on that Saturday afternoon in August 1973, it’s unclear, in an age before fax machines, let alone e-mail, how many of the other justices had laid eyes on the written opinion Douglas filed that morning, instead of merely having it summarized for them.

Either way, having the full Court act quickly without full briefing and argument had clearly not served the justices well during the Cambodia affair, a lesson they would forget as the practice became more common in subsequent years. Today, Holtzman v. Schlesinger is considered an obscure footnote (if it is considered at all). But in retrospect, it was an inflection point in the history of how the Supreme Court handles procedural applications. The Court’s disposition of the Cambodia affair marked (and helped to precipitate) a shift in the justices’ willingness to collectively—rather than individually—decide controversial and widely impactful matters behind closed doors. In retrospect, it was an early portent of a dramatic uptick in equally troubling and equally behind-the-scenes Supreme Court rulings to come. Those rulings would include even less reasoning than the four contradictory opinions filed by Marshall and Douglas over the first four days of August 1973—and, increasingly, they have had even more of an impact.

SCOTUS Trivia: In-Chambers Opinions

Holtzman was unique in that it generated four different in-chambers opinions, i.e., opinions by circuit justices respecting applications or other one-justice motions. As I’ve noted before, the once-robust practice of writing in-chambers opinions has become largely moribund—with Chief Justice Roberts’s March 2024 opinion in Navarro v. United States the only one that has been filed since 2014.

The Supreme Court started officially publishing in-chambers opinions as part of the United States Reports only in the October 1969 Term. But thanks to the herculean efforts of Cynthia Rapp (formerly of the Supreme Court Clerk’s Office), Professor Ross Davies, and Ira Brad Matetsky, there’s now a compendium of as many in-chambers opinions as that trio has been able to track down, including a ton of pre-1969 examples. The entire collection can be found here. There are some pretty remarkable entries in the collection—Justice Bradley’s 1882 denial of a writ of habeas corpus to Charles Guiteau (President Garfield’s assassin); a pair of 1927 denials of emergency relief to Sacco and Vanzetti; and a slew of more modern examples. The introduction to the collection has more useful background.

Separate from the archival point (that there are plenty of significant Supreme Court decisions that one would not find simply by searching the U.S. Reports) or the academic curiosities of individual cases, the key takeaway for present purposes is the volume: Circuit justices regularly wrote (brief) opinions respecting high-profile emergency applications. The lack of writing in these cases today really does appear to be a byproduct of the post-1980 shift to having so many emergency applications resolved by the full Court—and not a long-settled norm from which contemporary critics are asking the justices to depart.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one!

This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday.

Today’s “long read” is adapted, with some minor edits, from the Introduction to The Shadow Docket.

How many times does it appear that the vagaries, petulance, and prejudices of the Justices have been in play in life or death decisions, rather than a clear headed, honest, and courageous consideration of the rule of law? Seems, at times, it is not a “Supreme” Court; it is, instead, the “Court of Human Folly, Fallacy, and Failure.”

Nixon’s conduct in Cambodia still grinds my gears. For all Trump’s domestic illegality, it doesn’t come close to matching Nixon’s death in the world. And in contemporary terms, I blame the deaths due to DOGE cuts on Musk and Russ Vaught.