187. "Regular Forces" and the Insurrection Act

The supplemental briefing order in the Illinois National Guard case provides an obvious way for the Court to block President Trump's deployments to date—and a fair concern about what could come next.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to lawyers and non-lawyers alike. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current issues, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

The biggest news out of the Court last week was the Wednesday afternoon order in the Illinois National Guard case—in which the justices asked the parties to provide supplemental briefs on a substantive argument against the Trump administration that, as I’d noted previously, my friend and Georgetown Law colleague Marty Lederman had flagged in a friend-of-the-Court brief. For reasons I’ll elaborate upon below, my own view is that this briefing order is a pretty good sign for those who think the Court should deny the Trump administration’s application (and thereby leave on hold his attempted deployment of federalized National Guard troops into and around Chicago).

The trickier part is whether, as some have worried, adopting that argument would simply provoke the Trump administration into invoking the Insurrection Act—the scarier and even-older statute authorizing domestic use of the regular military, even for ordinary federal law enforcement. But as I suggest in the post that follows, two different things are necessarily true: First, my own view—and, more importantly, the longstanding view of the Department of Justice—is that the factual predicates for invoking the Insurrection Act are meaningfully more restrictive than the statute on which President Trump has relied to date (and than the facts on the ground would remotely support).

And second, insofar as that’s wrong, it suggests that nothing is currently stopping the Trump administration from invoking the Insurrection Act. If so, there are good reasons to shift the focus of the legal debate to the scope of that statute and its precedents (and historical interpretations), rather than an obscure law Congress passed in 1908 that was never intended to—and shouldn’t—be used the way President Trump has to date, i.e., as an ersatz Insurrection Act.

But first, the (other) news.

On the Docket

The Merits Docket

This will be short; the Court didn’t issue a regular Order List last week, and it took no other public action on any pending merits cases.

The Emergency Docket

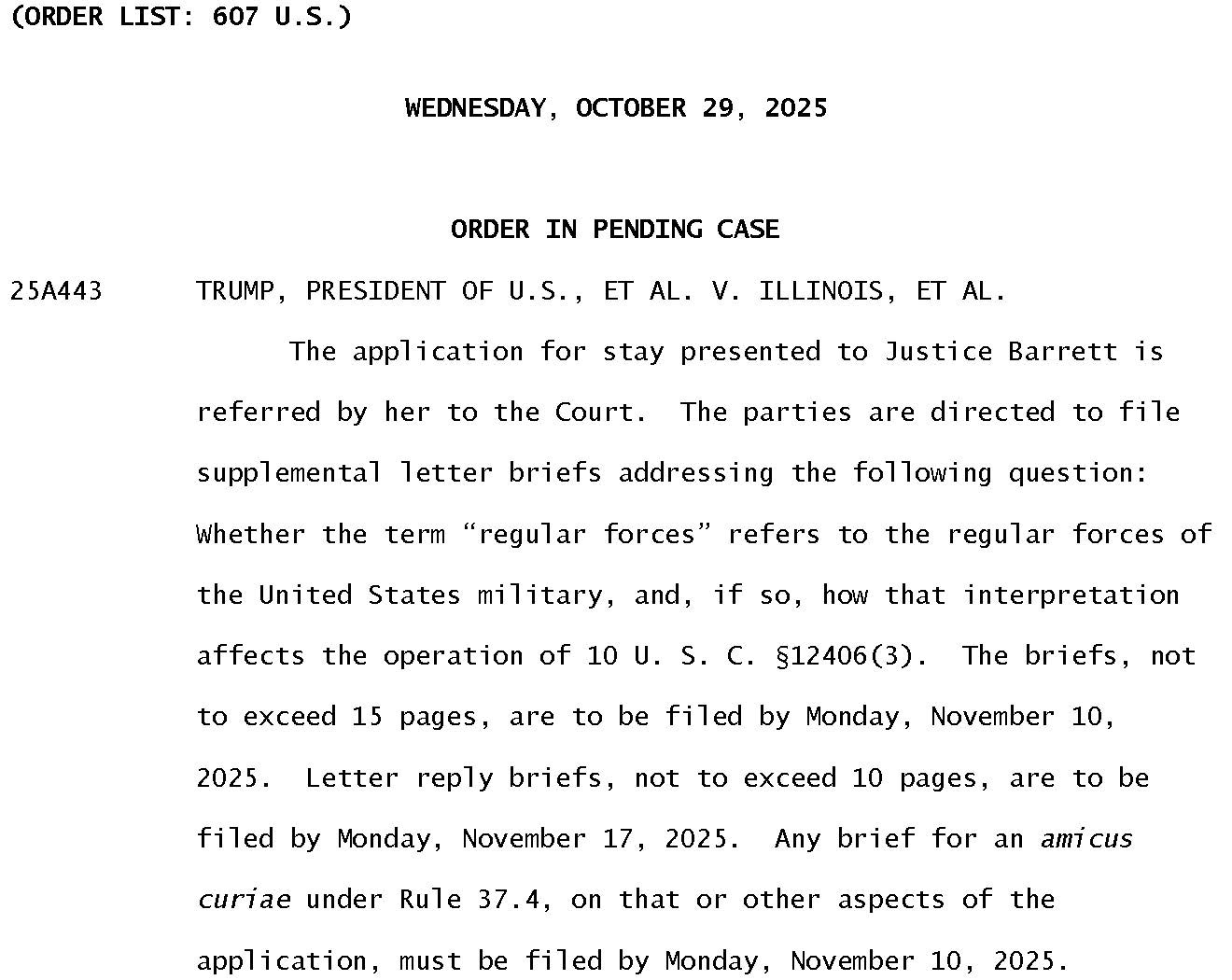

Indeed, the full Court issued only a single order last week—and it didn’t resolve anything. Instead, Wednesday brought the supplemental briefing order linked to above—directing the parties in Trump v. Illinois to address “Whether the term ‘regular forces’ refers to the regular forces of the United States military, and, if so, how that interpretation affects the operation of 10 U. S. C. § 12406(3).” I’ll explain in detail exactly what this is asking—and why I think it’s a good sign for Illinois—below. For now, the key point is that the order doesn’t have the reply briefs due until two weeks from today—Monday, November 17. That means there’s no reason to expect a ruling from the Court on this (immensely important) application before then—and the status quo is that the troops can’t be deployed.

The lack of other action from the Court included no ruling in Trump v. Orr (in which the Trump administration is trying to put back into effect a new State Department policy requiring passports to display the bearer’s biological sex at birth even if their gender identity is different). Orr has now taken more time from filing to a decision (45 days and counting) than any of the other applications from the Trump administration that have been decided without oral argument.1 I really don’t have any good explanation for why this one, in particular, is taking so long. But maybe it’s because (for once) the dissents are coming from the other side of the Court?

And speaking of emergency applications from the Trump administration, another one (the 30th) was filed last Monday—in Blanche v. Perlmutter. This one involves President Trump’s efforts to fire without cause the Register of Copyrights, who sits (and serves) in the Library of … Congress. A federal statute authorizes only the Librarian of Congress (who is appointed by the President subject to the advice and consent of the Senate) to remove the Register of Copyrights, so President Trump purported to remove the previous Librarian and appoint Todd Blanche (also the Deputy Attorney General) as Acting Librarian. Blanche then purported to fire Perlmutter.

Perlmutter sued, challenging the validity of Blanche’s action on the ground that he wasn’t properly appointed as Acting Librarian—because, she argued, the Library of Congress isn’t an “executive agency” to which the Federal Vacancies Reform Act applies. Indeed, one might point out that the fact that the President appoints the Librarian of Congress doesn’t prove that the Library of Congress is in the executive branch any more than his power to appoint judges and justices puts the courts under Article II. At the very least, Perlmutter’s suit presents a very different type of question about appointments and removals than the unitary executive theory issues raised in Wilcox, Boyle, Slaughter, and Cook.

Anyway, after the district court refused to issue a preliminary injunction, a divided panel of the D.C. Circuit issued an injunction pending appeal—which is what the Trump administration is now asking the justices to stay. Chief Justice Roberts, as Circuit Justice for the D.C. Circuit, has ordered Perlmutter to respond by 4 p.m. (EST) next Monday, November 10, so we may well have a ruling on this copyright “emergency” sometime next week—or not.

The Week Ahead

We do not expect the Court to hand down a regular Order List later this morning (no Conference last week). But the November argument session kicks off at 10:00 ET. (It appears that the Court is moving ahead with fully public arguments notwithstanding the shutdown.) The headline argument of the November session will surely be Wednesday’s arguments in the tariffs cases—which, time permitting, I’m hoping to preview in an extra issue of the newsletter between now and then (and which President Trump, after all that, says he will not be attending).

Miscellaneous

Finally, I wanted to briefly note a story in Saturday’s New York Times that has received a lot of attention, at least in law professor land—Jodi Kantor’s latest reporting on the “debate dividing the Supreme Court’s liberal justices.” I am a big fan of Kantor and her work, and regularly rely upon her behind-the-scenes reporting on the Court. That said, I think the headline (which Kantor surely didn’t write) reflects a slightly different piece—and alludes to a sharper conflict—than what she actually reported. As I noted back in July in the context of Justice Kagan’s concurrence in the Court’s second ruling in the D.V.D. case, what Kantor calls the “a generational and philosophical struggle over whether to safeguard institutions from within or protest their decline” has been visible in the opinions and votes of the Democratic appointees on Trump-related emergency applications since early April.

If anything, that divide got smaller over the summer; in the four months since the second D.V.D. ruling, there hasn’t been a single ruling on a Trump-related emergency application from which Justices Sotomayor and Jackson publicly dissented, and Justice Kagan didn’t.2 More than that, Justice Kagan fully joined Justice Sotomayor’s (understandably) angry dissenting opinion in Vasquez Perdomo; and her dissent in McMahon (the Department of Education downsizing case). And Justice Kagan has written her own (by her standards) fiery dissents—in Boyle, Slaughter, and AVAC II. Which is just to say that, although the debate Kantor describes certainly persists both inside and outside the Court, the real story, in my view, is how much the gap between Kagan and the other two Democratic appointees has shrunk over the last few months—and what that may signal about Justice Kagan’s declining faith in both her own (formidable) consensus-building skills and in the colleagues to her right.

The One First “Long Read”:

Who are the “Regular Forces”?

For the sake of efficiency, I’m going to assume at least some familiarity with the general background to Trump v. Illinois—the Trump administration’s application asking the Supreme Court to stay a district court TRO (that it agreed to extend!) blocking the deployment of federalized National Guard troops into and around Chicago. If you could use a refresher, see this post.

The Path to the Supplemental Briefing Order

To make a long story short, on the “merits” of the lawsuit, the Trump administration has three arguments for why it’s likely to prevail: First, that the President’s invocation of this obscure National Guard federalization statute, 10 U.S.C. § 12406, isn’t subject to judicial review at all; second, that, in any event, the President validly invoked § 12406(2)—because “there is a rebellion or danger of a rebellion against the authority of the Government of the United States” in and around Chicago; and third, that the President also validly invoked § 12406(3)—because he “is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.” With regard to this last provision, the Trump administration’s position all along has been that, in referring to “the regular forces,” § 12406(3) is describing federal civilian law enforcement authorities. Thus, its argument goes, the ICE-related protests in and around Chicago are leaving the President “unable” to execute the laws with those personnel whose activities are being impeded.

In all three of the state cases (in which this issue has arisen), much of the focus has been on whether that’s actually true—i.e., whether protests, even those that have included unlawful activity, have really left the President “unable” to execute federal law in Los Angeles, Portland, and Chicago (indeed, there’s plenty of evidence to the contrary). But in the Illinois case, Judge Perry,3 in the district court, had also relied upon another point—that § 12406(3)’s reference to “the regular forces” is solely a reference to the active-duty military, which President Trump has not even tried to use there yet. Thus, one need not decide the factual question if there’s no legal basis for invoking § 12406(3) regardless of the facts.

Because the Seventh Circuit relied more on the factual point, the application in the Supreme Court—and Illinois’s response—did not play up this issue, and instead focused on the discretion to which the President should (or shouldn’t) be entitled when determining what’s true on the ground. But this was the whole point of Professor Lederman’s amicus brief, i.e., that the Court could avoid the messy question of how much deference to give the President when it comes to whether he’s really “unable” to execute the laws by holding that he hasn’t even tried to do so with “the regular forces”—as the statute means the term. Even justices who might be broadly willing to defer to the President with regard to the facts might nevertheless be attracted to that legal defect in his deployments to date—which would doom not just the Illinois efforts, but also the (currently blocked) federalization in Oregon and the (currently not blocked) federalization in California.

The fact that the Court issued this briefing order thus suggests at least four things: First, there aren’t five votes for the Trump administration on the non-reviewability issue (because, if there were, there’d be no need to ask about § 12406(3)); second, there aren’t five votes on the “rebellion” issue (ditto); third, the Court finds this argument plausible enough to at least require the Justice Department to respond; and fourth, the Court is comfortable keeping Judge Perry’s TRO in place for at least 2.5 more weeks (the time from when it issued the briefing order through when the reply briefs are due). Whatever else might be said about the additional question the justices posed (about which more shortly), all of those are, in my view, good signs for Illinois.

Who Are the “Regular Forces”?

As I suggested last week, folks should read Professor Lederman’s amicus brief for themselves, but my own view is that he is clearly and unequivocally correct—that Congress used the term “regular forces” in the 1908 statute creating present-day § 12406(3) unambiguously as a reference to the standing federal military, where “regular” is used in distinction to “irregular,” i.e., part-time. The brief marshals countless contextual examples of Congress using that term to refer to the full-time military—and no one else. And as Lederman explains, various other features of the statute (including the two uses of the word “Regular” in 10 U.S.C. § 12405) just wouldn’t make sense if “regular forces” meant every single civilian federal officer with any ability to undertake law enforcement duties.

I’ll just add that the whole point of the 1908 statute was to reconcile the 1903 creation of the modern National Guard (which is a state-federal hybrid) with the existing statutes authorizing domestic deployment of federal “regulars.” As I’ve explained before, the National Guard is really two different entities—the National Guard of the United States and the (individual) National Guard of the different states and federal territories. Thus, “regular forces” in the 1908 Act was a way of distinguishing between National Guard personnel (who, once federalized, are also federal troops, but aren’t otherwise) and those whose permanent billets were in federal military service. And although § 12406(1) and (2) authorize the President to federalize the National Guard without waiting for the regulars in cases of invasion or rebellion, it makes sense that Congress would have wanted the state National Guard to be the fallback, not the first line of defense, in circumstances in which what required federal military intervention was a breakdown of local authority (since governors would otherwise be free to call out their own National Guards in circumstances warranting it).

Obviously, the parties (and other amici) will now have a chance to weigh in on Professor Lederman’s research and arguments, but I’ll just say that I’ll be surprised if the Trump administration is able to muster contrary textual or contextual arguments—versus a policy argument that its reading of § 12406(3) makes sense in the light of allowing the President to use the National Guard before resorting to the stronger medicine of calling out active-duty troops under the Insurrection Act.

On the flip side, I also think there’s (understandable) concern that a ruling embracing Professor Lederman’s reading of § 12406(3)—that President Trump can’t federalize the National Guard because he hasn’t even tried to use full-time military personnel—will just provoke Trump into trying that move next, by invoking the Insurrection Act. Both of these arguments are asking the same question, albeit from very different perspectives (and policy concerns). For what it’s worth, that shouldn’t change the meaning of the statute. But it does seem worth explaining why I don’t find either side of this claim persuasive—and why it ought not to figure into how the Court resolves the current application.

The Insurrection Act Elephant in the Room

To jump to the end, the reason why the Insurrection Act is the elephant in the room is because there’s no debate that, once it is properly invoked, it authorizes domestic law enforcement by the military—i.e., it is an exception to the ban on such behavior in the Posse Comitatus Act. As Judge Breyer explained in the California case, that is not true of § 12406(3), at least without a concomitant Insurrection Act invocation. So from the Justice Department’s position, § 12406(3) is a lesser authority for domestic use of the military; and from the other end, taking away § 12406(3) would leave President Trump to choose between the Insurrection Act and nothing—and he’s not likely to opt for the latter.

To me, both sides of this argument miss two points. The first one is that there is a whole lot of daylight between the trigger for § 12406(3) (is the President “unable” to execute federal law with the “regular forces”) and the far-stricter triggers for the two relevant Insurrection Act provisions, 10 U.S.C. §§ 252 and 253. Section 252, for instance, applies only if “unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States, make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States in any State by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.” That’s a lot more specific than a vague “inability.”

As for § 253, that provision likewise has more specific triggers. Even its most capacious provision, § 253(2), authorizes use of the military only when “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy . . . opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws.” In other words, random acts of protestors that impede ICE operations wouldn’t qualify—especially if, as is true in Illinois, local and state officials are actively enforcing state laws against the protestors.

But don’t take my word for it; as Professor Lederman flagged in his amicus brief, then-Deputy Attorney General Nicholas deB. Katzenbach was comprehensively summarizing the Department of Justice’s historical understanding when he wrote in a 1964 memorandum (with my emphasis added) that these statutes

have always been interpreted as requiring, as a prerequisite to action by the President, the conditions described above: that state authorities are either directly involved, by acting or failing to act, in denials of federal rights of a dimension requiring federal military action, or are so helpless in the face of private violence that the private activity has taken on the character of state action. The degree of breakdown in state authority that is required undoubtedly is less where a federal court order is involved, for there the power of the federal government is asserted not simply to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment, but to defend the authority and integrity of the federal courts under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution. But where no court order is involved, reliance must be placed on the premise that those engaging in violence are either acting with the approval of state authorities or have, like the Klan in the 1870s, taken over effective control of the area involved.

In other words, and unlike § 12406(3), the Insurrection Act requires much more than just some degree of impairment of federal law enforcement; it requires a breakdown caused by the state’s unwillingness or inability to enforce its own laws or abide by federal court orders. That’s a much higher bar to clear. (Katzenbach also suggested that, before invoking those statutes, “the [federal] government should have [significant evidence] of the inability of state and local officials to maintain law and order—as a matter of wisdom as well as of law.”)

Of course, the Katzenbach memo is just the internal opinion of the Department of Justice. But its significance is in the extent to which it reflects both how that Department has always interpreted the Insurrection Act and its summary of the actual historical uses of the statute—to which the situations in California, Oregon, and Illinois bear not even the faintest resemblance.

This reality is, in my view, the key to understanding the stakes of the Court’s embrace of the Lederman position. With regard to the argument that the National Guard ought to come first, that makes no sense as a historical matter (the Guard was, after all, brand new when § 12406 was enacted; it had none of the experience that might justify such a pecking order; and, in any event, nothing prevented a governor from calling out their own Guard if circumstances warranted it); and, if accepted, it would turn § 12406(3) into a poor man’s Insurrection Act—allowing the President to introduce federal troops in circumstances that don’t come close to the historical threshold. Nor is the Posse Comitatus Act much consolation in that circumstance—because, as we’ve already seen, the broad deployment of troops domestically is plenty coercive even if they can’t conduct immigration raids and arrests themselves.

It is, of course, a serious concern that a Supreme Court ruling formally (or even effectively) cutting off use of § 12406(3) here will provoke the Trump administration into invoking the Insurrection Act anyway. To that, I have two responses. First, putting the statutory formalities aside, I don’t see how we’re that much better off in a world in which the Court allows the President to use § 12406(3) whenever he makes even the most remotely plausible claim that federal law enforcement efforts have been impeded—i.e., if it grants the current application.

Even if the line we ended up with was the one drawn by the Posse Comitatus Act (no use of the National Guard for law enforcement, as such), that would still clear the way for the President to deploy troops into any jurisdiction in which he or his policies are being protested—deployments that will be enormously disruptive and coercive, especially as they get larger and more ubiquitous. That is to say, although I’d certainly prefer a world in which courts were vigorously scrutinizing the President’s factual determinations in this space, I don’t think that’s a likely outcome here. And if not, then the alternative of effectively unreviewable authority under § 12406(3) seems no better to me.

Second, and in any event, either there is a meaningful difference between the factual predicate for invoking § 12406(3) and the Insurrection Act or there isn’t. If the former is true, then a ruling holding (or, at least, producing the effect) that President Trump can’t use § 12406(3) until the “regular forces” have been unable to restore order will not necessarily lead to an Insurrection Act invocation—or, if it does, there will be lots of ground on which to challenge whether the substantive triggers are met in that case. And if the latter is true, i.e., if there’s no difference, then nothing is stopping the President from invoking the Insurrection Act already—a reality that ought to scare the bejeezus out of everyone.4

All of this is to say that I think two things are true: § 12406(3) does not allow federalization of National Guard troops unless regular military forces are “unable” to execute the laws of the union; and there would be no factual or legal basis, at least today, for President Trump to try to use regular military forces under the Insurrection Act to do so. Against that backdrop, the Court should deny the application in Trump v. Illinois—and folks who are opposed to President Trump’s domestic uses of the military should unhesitatingly welcome such a result.

SCOTUS Trivia:

Supplemental Briefing on Applications

Even casual readers of this newsletter likely know that I follow the Supreme Court’s behavior on emergency applications rather obsessively closely. I was, thus, a bit surprised by Wednesday’s order—not because the § 12406(3) issue flagged by Professor Lederman isn’t important, but because the Court’s norm on emergency applications for as long as I’ve been studying them is to not solicit additional briefs—even from the parties, and even in the cases it has set for oral argument.

This led me to try to identify any prior examples of the Court ordering additional briefing respecting an application. Sometimes, when the Court treats an application as a petition for plenary review and grants it (as it did in Slaughter, TikTok, and the Title 42 cases, just in recent memory), it will, quite naturally, identify the question(s) the parties should brief and argue on the merits. But my own research hasn’t identified a single prior application in which the Court asked the parties for additional briefs without taking any action in the case. The closest I could find was the application in Trump v. Cook, which the Court has set for argument in January. There, the Court’s order deferring resolution pending that argument provided that “The Clerk is directed to establish a briefing schedule for amici curiae and any supplemental briefs responding to amici.” That’s quite obviously closer, but still not what happened in Illinois. And in the four other recent examples of the Court setting applications for argument, it included no similar invitation.

This point seems more than trivial to me, for it underscores, yet again, how much the Court is increasingly treating emergency applications like any other case—not in a necessarily bad way (quite to the contrary, here!), but in a way that would surely benefit from a more comprehensive set of rules and norms than the status quo of individual, case-by-case accommodations.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one:

This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday. Have a great week, all!

The previous clubhouse leader was Trump v. Wilcox, which took 43 days from filing to decision. Only CASA (the birthright citizenship cases, which the Court decided after oral argument) took longer—and even there, the order setting the applications for oral argument came 35 days after they were filed.

The only post-D.V.D. II ruling reflecting public division among the Democratic appointees was Trump v. AFGE, in which only Justice Jackson publicly dissented (and Justice Sotomayor wrote a concurrence).

An earlier version of this post misidentified the district judge as Judge Ellis (who has the distinct case about ICE’s use of force in and around Chicago).

I’ve had some folks suggest to me, offline, that they’re worried that the Supreme Court, in denying this application based upon the § 12406(3) argument, might overtly acknowledge the availability of the Insurrection Act. I am pretty darn cynical about this Court’s behavior on emergency applications, but even I have a hard time believing there would be five votes to preemptively answer such a momentous question in a context in which it isn’t remotely presented and hasn’t been briefed. And if there are, then we have bigger problems.

Steve's brief discussion of Jodi Kantor's piece on a rift among the liberal Justices is helpful. Especially his demonstration that the have been more unified in recent months.

I don't know the history of this statute, but I do know a fair bit of U.S. history. And I have a fair bit of relevant real-world experience. An extremely good and important functional reason may underlie the requirement to use of regular forces instead of militias. Historically, in the U.S. regular forces were much more professional and much more disciplined than any militia. Too often, militias chose their own leaders, and they too often were no better than a heavily-armed, wildly uncontrollable mob.

I'm speaking especially about the militia's of the mid-to-late 1800's (including in conflicts with Native Americans and our Spanish or Mexican neighbors). But as early as the start of the Revolutionary War, regular soldiers and national leaders saw the need for a national army because militias were so dangerously undisciplined that their participation undermined the discipline and effectiveness of even the regular forces. See, e.g., https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/September-30/washington-blames-militia-for-problems