171. Partisan Gerrymandering After Rucho

The Supreme Court isn't responsible for partisan gerrymandering. But current events in Texas underscore how much its 2019 ruling in Rucho has left (some) states free to radically abuse the practice.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); and we’ll usually have a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current issues, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

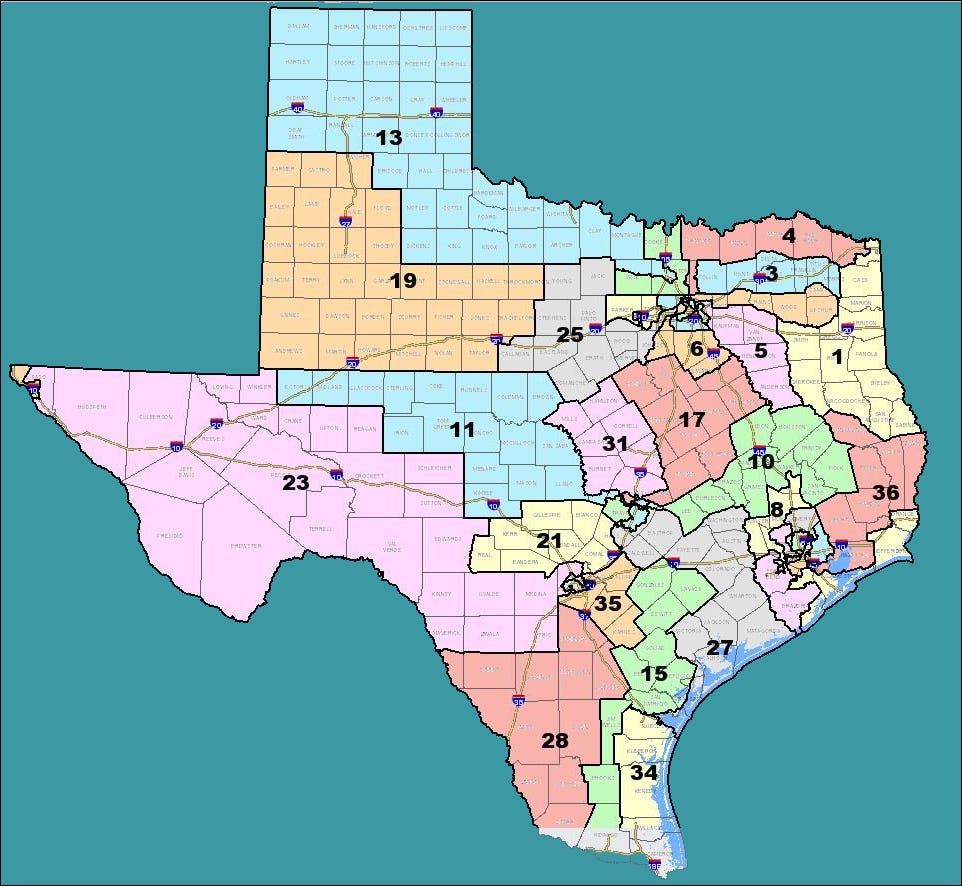

There’s an unusual amount to discuss for the first week of August. But I thought I’d use today’s issue to focus on one especially prominent story in the news—the unabashed efforts of Texas Republicans to re-draw the state’s 38 districts in the U.S. House of Representatives for no reason other than to create four or five additional “safe” seats for Republican candidates in the 2026 congressional elections. At the moment, Democratic members of the Texas legislature have fled the state in an effort to deprive the legislature of a quorum. But assuming that the new map will eventually make it into law, the result will be to take a state that, at the time of the last Census, saw only a 52.0%-46.5% R/D split in the presidential election—and leave it with a likely 30R/8D House delegation in the 120th Congress (that’s 79%-21%).1

The point is not to single-out Republicans, though; at least some Democratic-led states draw severely gerrymandered districts, too. Rather, the larger issue is with the Supreme Court—and, specifically, its 2019 ruling in Rucho v. Common Cause, in which a 5-4 majority held that federal courts can’t entertain challenges to partisan gerrymandering on federal constitutional grounds—not because those grounds don’t exist, but because such suits lack “judicially manageable standards.” The Rucho majority’s unwillingness to articulate such standards given the other constitutional claims for which the Court has shown no comparable reticence to craft its own standards was deeply exasperating at the time—and looks that much worse each time a state (of any color) tries to pull a stunt like what Texas is currently attempting.

To be sure, partisan gerrymandering didn’t begin with Rucho. But for those states that (1) leave the line-drawing to their legislatures; and (2) don’t recognize meaningful state constitutional limits on partisan gerrymanders, Rucho got rid of the last legal obstacle. And although folks will debate in perpetuity whether partisan gerrymandering is better in the nationwide aggregate for Democrats or Republicans (or neither), two points seem undeniable: Partisan gerrymandering tends to make primary elections far more important than the general election (the result of which is to exacerbate political polarization); and mid-decennial gerrymandering, like what Texas is attempting now, is especially pernicious. Against that backdrop, it’s fascinating to wonder how things might look today if Rucho had come out differently.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

The biggest news out of the Court last week came right at the end of it—when, right around 5:15 p.m. ET on Friday (I’m sure the timing was a total coincidence), the Court handed down the much-anticipated “supplemental briefing” order in the Louisiana racial gerrymandering cases. As folks might remember, these cases had been argued last term, only to have the Court hand down a surprising order on the last day it handed down decisions in argued cases in June noting that they would be re-argued next term—and that the questions to be briefed would be provided at some point in the future. That point came Friday, with the justices instructing the parties to address “Whether the State’s intentional creation of a second majority-minority congressional district violates the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments to the U. S. Constitution.”

As election law scholars like my friend and UCLA law professor Rick Hasen were quick to point out, the new question is worded in a way that may open the door to the justices considering whether the Voting Rights Act’s central substantive provision (section 2), which has long been interpreted by the Supreme Court to require the intentional creation of such districts in some cases to ensure adequate representation of racial minority groups, is itself unconstitutional. That would be quite a remarkable (and, in my view, ridiculous) holding. Either way, though, the Louisiana gerrymandering cases, which will likely be argued during the Court’s October or November sitting, just became even more important.

The only other action out of the full Court last week was Thursday’s denial, over no public dissents, of a stay of execution to Florida death-row inmate Edward Zakrzewski.

Away from the Court, Justice Kavanaugh made headlines with his annual appearance at the Eighth Circuit Judicial Conference—where, contra the remarks from the previous week by Justice Kagan, he sought to defend the Court’s practice of sometimes granting emergency relief without providing any written explanation. Frankly, I’m not sure Kavanaugh said anything new (except for folks who aren’t as familiar with his concurrences in Labrador and CASA). I’ll just note that I think my post from two weeks ago laying out all of the defenses of not writing, and then explaining why they fail to persuade, still holds up.

Turning to this week, nothing formal is expected from the Court. The justices continue to sit on at least three (sets of) high-profile emergency applications (in the NIH funding case; the Mississippi social media age-verification case; and a Tennessee death-row case), all of which I discussed in last week’s issue, and all of which are (I think) now ripe for a decision.

The One First “Long Read”:

Rucho Ado About Nothing

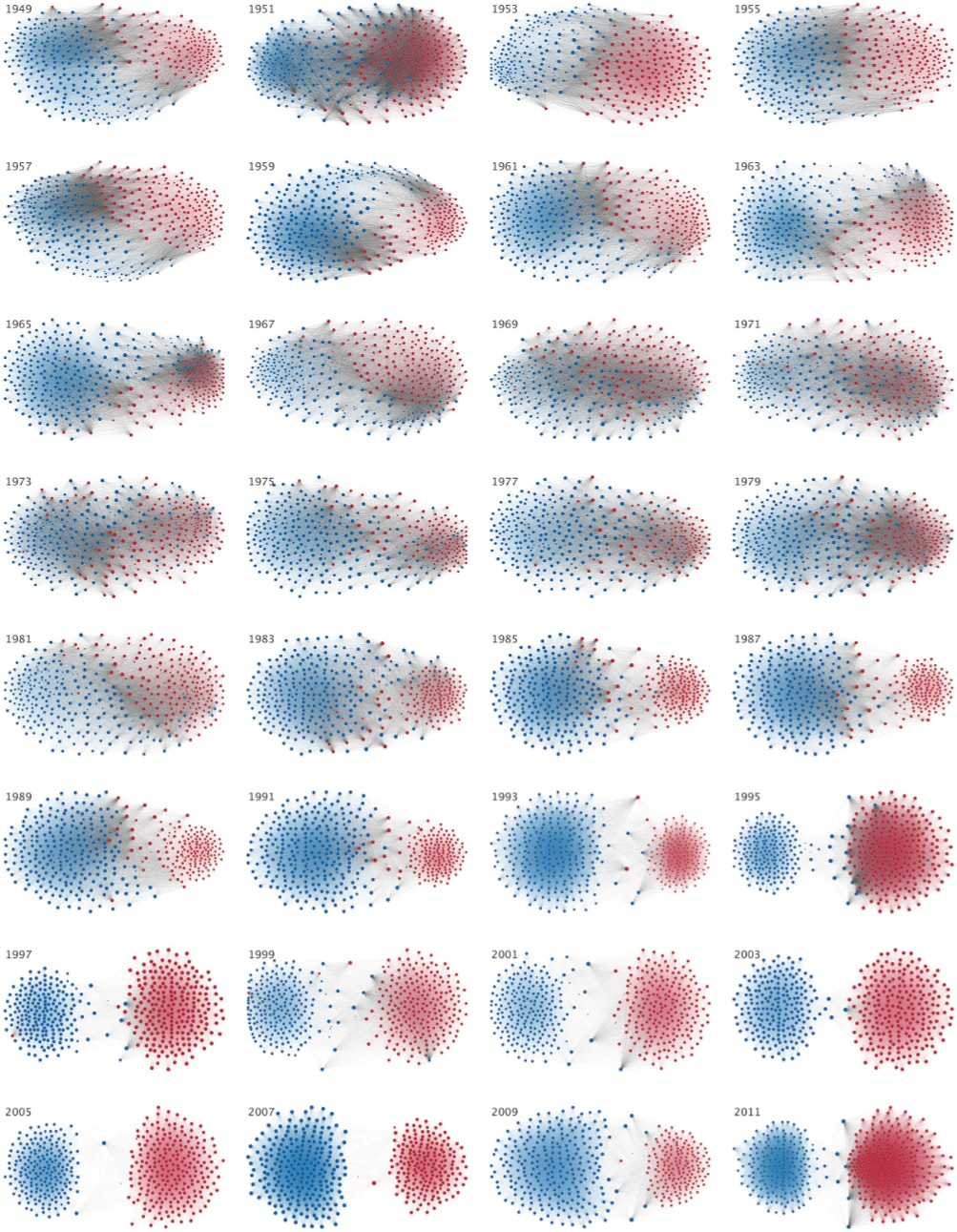

In a remarkable 2015 paper, six academics created a series of visualizations based upon network relationships among the 435 members of each House of Representatives dating back to 1949—tracking how often each member cooperated on bills with other members, including members of the other party. The time-lapse video version of the data is worth watching, but even this static image powerfully captures one of their central points—i.e., the increased polarization of the House (and the demise of a meaningful “middle”), especially starting in the mid-1990s. That polarization is reflected not just in the sorting of the colors into increasingly separated spaces, but the virtual disappearance of any networks between members of the two parties:

Political scientists and other scholars have long debated how much of this can be traced to partisan gerrymandering—the practice of drawing a state’s congressional districts to maximize the advantage for whichever party currently controls that state’s legislature—versus other factors. After all, six states have no district lines to draw (they each have only a single district). What seems clear beyond peradventure, though, is that partisan gerrymandering is at least part of the story here—and that, at a minimum, it is exacerbating this phenomenon—whether or not it helped to cause it in the first place.

1. Partisan Gerrymandering and the Court

The background here is, hopefully, somewhat familiar. The Constitution requires a Census every 10 years, and Congress in a series of “reapportionment” acts, has provided for the reapportionment of seats in the House of Representatives into single-member districts based upon the results of each decennial Census. As a result, many states have to engage in redistricting once a decade (and most states choose to do so—since district sizes may change even if a state’s allotment of seats in the House doesn’t).

The practice of “political” (or “partisan”) gerrymandering dates back, at least loosely, to the coinage of the term—a portmanteau to describe a salamander-shaped Massachusetts state senate district signed into law by then-Governor Elbridge Gerry in 1812. But it’s only been with the advent of modern technology (especially with respect to localized mapping) that efforts to maximize “packing” and “cracking” have truly taken off.

To that end, the Supreme Court was first asked to seriously grapple with the constitutionality of “severe” partisan gerrymandering in the mid-1980s.2 In Davis v. Bandemer, a four-justice plurality, in an opinion by Justice Byron White, held that federal courts could hear claims that a partisan gerrymander violated the Equal Protection Clause—but that the plaintiffs in that case hadn’t shown that maps drawn by the Indiana legislature were “sufficiently adverse” to state a federal constitutional violation. Three justices (Chief Justice Burger and Justices Rehnquist and O’Connor) would have held such claims to be non-justiciable. And two justices (Powell and Stevens) agreed that federal courts could entertain partisan gerrymandering claims, but disagreed with the standard the majority adopted. In other words, a majority of the Court thought federal courts could resolve such claims, but—critically—couldn’t agree as to how.

The Court next directly confronted the issue in 2004—in Vieth v. Jubelirer, a challenge to Pennsylvania’s redistricting after the 2000 Census. Four justices (in an opinion by Justice Scalia) would have embraced the O’Connor view from Davis—that federal courts can’t resolve partisan gerrymandering claims. Four justices (Justices Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer) dissented. That left Justice Kennedy—who concurred in the judgment, writing that he believed federal courts could resolve partisan gerrymandering claims, but that they had not yet been presented with a satisfying standard for doing so.

Two years later, in LULAC v. Perry, the Court (with two new justices) fractured along analogous lines in a challenge to Texas’s mid-decennial redistricting. The Vieth dissenters (Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer) would have, once again, held that challenges to severe partisan gerrymandering could be entertained by federal courts. And two of the dissenters (Stevens and Breyer) would have struck down Texas’s plan in its entirety. Meanwhile, Justice Kennedy once again sought to split the difference—continuing to take the position that federal courts could resolve partisan gerrymandering claims with the right standard, but that such a standard hadn’t been identified (yet). Critically, LULAC rejected the argument that voluntary, mid-decennial redistricting is inherently problematic.

That unstable equipoise largely persisted until 2018—when Justice Kavanaugh replaced Justice Kennedy. It was only once Kavanaugh was on the Court that the justices agreed to take up new appeals in cases from Maryland and North Carolina once again asking for a definitive resolution on whether partisan gerrymandering is justiciable—and, if so, pursuant to what standard.

That resolution came on June 27, 2019. With Chief Justice Roberts writing for a 5-4 majority, the Court in Rucho v. Common Cause categorically closed the door on federal courts entertaining constitutional challenges to partisan gerrymandering—holding that the Constitution provides no yardstick by which to measure the degree of “unfairness” of one district versus another. As he put it,

And it is only after determining how to define fairness that you can even begin to answer the determinative question: “How much is too much?” At what point does permissible partisanship become unconstitutional? If compliance with traditional districting criteria is the fairness touchstone, for example, how much deviation from those criteria is constitutionally acceptable and how should map-drawers prioritize competing criteria? Should a court “reverse gerrymander” other parts of a State to counteract “natural” gerrymandering caused, for example, by the urban concentration of one party? If a districting plan protected half of the incumbents but redistricted the rest into head to head races, would that be constitutional? A court would have to rank the relative importance of those traditional criteria and weigh how much deviation from each to allow.

Justice Kagan wrote on behalf of all four dissenters (herself and Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor).3 Noting that she dissented “with respect but deep sadness,” she was clear-eyed about the consequences of the majority’s decision:

If left unchecked, gerrymanders like the ones here may irreparably damage our system of government. And checking them is not beyond the courts. The majority’s abdication comes just when courts across the country, including those below, have coalesced around manageable judicial standards to resolve partisan gerrymandering claims. Those standards satisfy the majority’s own benchmarks. They do not require—indeed, they do not permit—courts to rely on their own ideas of electoral fairness, whether proportional representation or any other. And they limit courts to correcting only egregious gerrymanders, so judges do not become omnipresent players in the political process. But yes, the standards used here do allow—as well they should—judicial intervention in the worst-of-the-worst cases of democratic subversion, causing blatant constitutional harms. In other words, they allow courts to undo partisan gerrymanders of the kind we face today from North Carolina and Maryland. In giving such gerrymanders a pass from judicial review, the majority goes tragically wrong.

And tellingly, as Kagan explained, there are viable (and judicially manageable) standards by which to assess the severity of a partisan gerrymander. The majority just did not find any of those standards satisfactory.4

2. Partisan Gerrymandering After Rucho

Six years after Rucho, and given what is currently transpiring in Texas, it is hard to disagree with Justice Kagan’s warning. Of course, some states have found their own ways of limiting partisan gerrymandering. 13 states have given the power to draw district maps to either non-partisan or bi-partisan commissions—a practice the Supreme Court upheld, albeit by a vulnerable 5-4 majority, in 2015. (Iowa also used a special process that insulates its redistricting from direct partisan control.) At least ten other states have seen their state supreme courts recognize state constitutional limits on partisan gerrymandering (as Justice Kagan pointed out in her Rucho dissent, if those courts could do it…).

The result is that effectively unlimited partisan gerrymandering is only available today in a (numerical) minority of states. But in those states that have not taken the redistricting power away from their legislatures, and whose supreme courts aren’t limiting those legislatures, Rucho has left it as open-season for whatever the legislature can get away with.

That brings us to what’s currently happening in Texas—where, at the urging of President Trump, the Republican-gerrymandered Texas legislature has proposed a radical, mid-decennial redistricting, for no purpose other than maximizing the Republicans’ partisan political advantage in the U.S. House of Representatives. As the New York Times suggests, the plan would leave zero of Texas’s 38 districts in which the margin in the 2024 presidential election was closer than 10 points. And in a state that is solidly but not overwhelmingly “red,” it would give Republicans a 4:1 advantage in the state’s House delegation.

Just to say it again, Democrats engage in partisan gerrymandering, too. And California Governor Gavin Newsom has threatened to retaliate against what Texas is proposing by adopting an even more extreme district map in the nation’s largest state. But there are reasons why we should all be averse to such a race to the bottom—even if, in a specific election cycle and/or in a particular state, it happens to benefit the party we support.

3. Two (Hopefully) Consensus Objections to Partisan Gerrymandering

Against this backdrop, it seems like there are two points that ought to be relatively uncontroversial, but that are worth saying out loud, nonetheless.

The first takeaway is that, regardless of the extent to which partisan gerrymandering is the cause of our contemporary political polarization, it has certainly exacerbated it. Take Texas’s proposal. If it succeeds, that will mean that, in all 38 House districts, the primary election will be more important (and, likely, closer) than the general election. But primary voters (in both parties) tend to be much further to the wings than general election voters—meaning that, to win primaries, candidates will have to run to their party’s flanks. The result is to return to Washington “representatives” who were elected by those least likely to support compromises with the other party—the very type of compromises that are usually at the heart of true institutional reform legislation (like legislation to reform partisan gerrymandering!).5 There are lots of reasons for why Congress has become so dysfunctional, but this dynamic in too many states is, in my view, a significant contributing factor.

In contrast, in a world in which severe partisan gerrymandering had at least some federal constitutional limits, there’d be that much more of an incentive for states to pursue approaches to redistricting with goals other than maximizing partisan political advantage—or, at the very least, for that maximization to itself be limited. A world in which more general elections were meaningfully contested is, to my view, a better world for ensuring that the House of Representatives plays the role the Founders intended (ditto to un-capping the House and making it more representative in general).

The second takeaway ought to also be un-controversial: For as much as legislatures need to re-draw House district maps after each Census, there ought to be a presumption against voluntary mid-decennial redistricting. For starters, such redistricting can’t be justified as implementing any federal constitutional command; Texas will have 38 seats in the 120th Congress without regard to how those district lines are drawn. Perhaps states can identify circumstances in which there is some compelling justification for redrawing lines without an intervening Census, but the burden should be on states in such circumstances—and that burden should be judicially enforceable.

I don’t mean to overstate things; one need look no further than the Senate (in which the equal representation of the states is guaranteed by the Constitution) to see that reining in partisan gerrymandering by state legislatures won’t “fix” the myriad problems with Congress overnight. But re-reading Justice Kagan’s Rucho dissent in 2025, especially as events unfold in Texas, is a powerful reminder that the Supreme Court has arguably made it only that much worse, and did so based upon an (at-best) naive view that the political process would somehow be able to provide adequate remedies for its own distortions and manipulations. The animating principle of our democracy, to quote Alexander Hamilton, is “that the people should choose whom they please to govern them.” But as Kagan concluded in Rucho, unchecked partisan gerrymandering “create[s] a world in which power does not flow from the people because they do not choose their governors.”

That may be good for Republicans in Texas today. It may be good for Democrats in California tomorrow. But it is profoundly bad for the United States as a constitutional democracy—and is an increasingly serious problem for which the Supreme Court bears at least some responsibility.

SCOTUS Trivia: Ten Opinions from Nine Justices

This is, alas, a repeat. But given how badly fractured the Court was in both Vieth and LULAC (especially the latter), I thought it would be useful to re-up the two cases in which nine justices somehow managed to produce ten opinions: New York Times v. United States (the “Pentagon Papers case”) and Furman v. Georgia. In both cases, every justice wrote their own opinion, and there was an unsigned “per curiam” opinion to speak, at least in part, for the majority.

As I wrote last year, “I’m just really glad that I didn’t have to help explain those rulings in realtime.” Ditto, Vieth and LULAC.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one:

This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday. Have a great week, all!

As the New York Times notes, under the proposed map, 30 of Texas’s 38 House districts would encompass areas President Trump won by at least 10 points in the 2024 election; eight would encompass areas then-Vice President Harris won by at least 10 points. None would encompass areas in which the election was closer.

In 1973, the Court had unanimously rejected the argument that “minor” variances in representation due to partisan gerrymandering violated the Equal Protection Clause.

I’ll confess that Justice Kagan’s Rucho dissent is my favorite single opinion of hers.

One of the most persuasive approaches, in my view, would be to focus on the “efficiency gap,” as Professor Nick Stephanopoulos and Eric McGhee (among others) have explained.

Indeed, the Freedom to Vote Act—a bill that would have significantly limited partisan gerrymandering—passed the (Democratic-controlled) House of Representatives in 2022, but couldn’t overcome a Republican-led filibuster in the Senate.

After the 1910 census the number of representatives increased from 386 to 435, and so it has remained to this day. Meanwhile the population has more than tripled – going from 92 million to 331 million. While the Senate and the Electoral College are often identified as threats to democracy, the House–the Constitution’s designated representative democracy–has been ignored as each citizen’s vote is watered down to near pointlessness.

Freezing House membership violated the intent of the drafters and ratifiers as well as the actual text of the Constitution. It has made apportionment of seats based on population mathematically impossible. Today, 991,000 people in Delaware share a representative while in Montana the number is 543,000 – an 83 percent discrepancy.

This website ( https://twoyearstodemocracy.com/ ) is a personal essay which describes and documents the 1929 usurpation, its consequences and the potential for reform. It is brief -- 1,700 words (8 to 10 minutes) and thought-provoking.

As Thomas Paine wrote in Common Sense, "… a long Habit of not thinking a Thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defence of Custom. But the Tumult soon subsides. Time makes more Converts than Reason."

Nothing to see or hear here -- just the end-stage respiratory gurgling of a dying patient.