Bonus 167: The Case for Not Writing

With the justices handing down so many significant grants of emergency relief without rationales, it's worth identifying the arguments in support of unexplained rulings—and why they fail to persuade.

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter (and unscheduled issues) will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, I put much of the weekly bonus issue behind a paywall as an added incentive for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and I hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit.

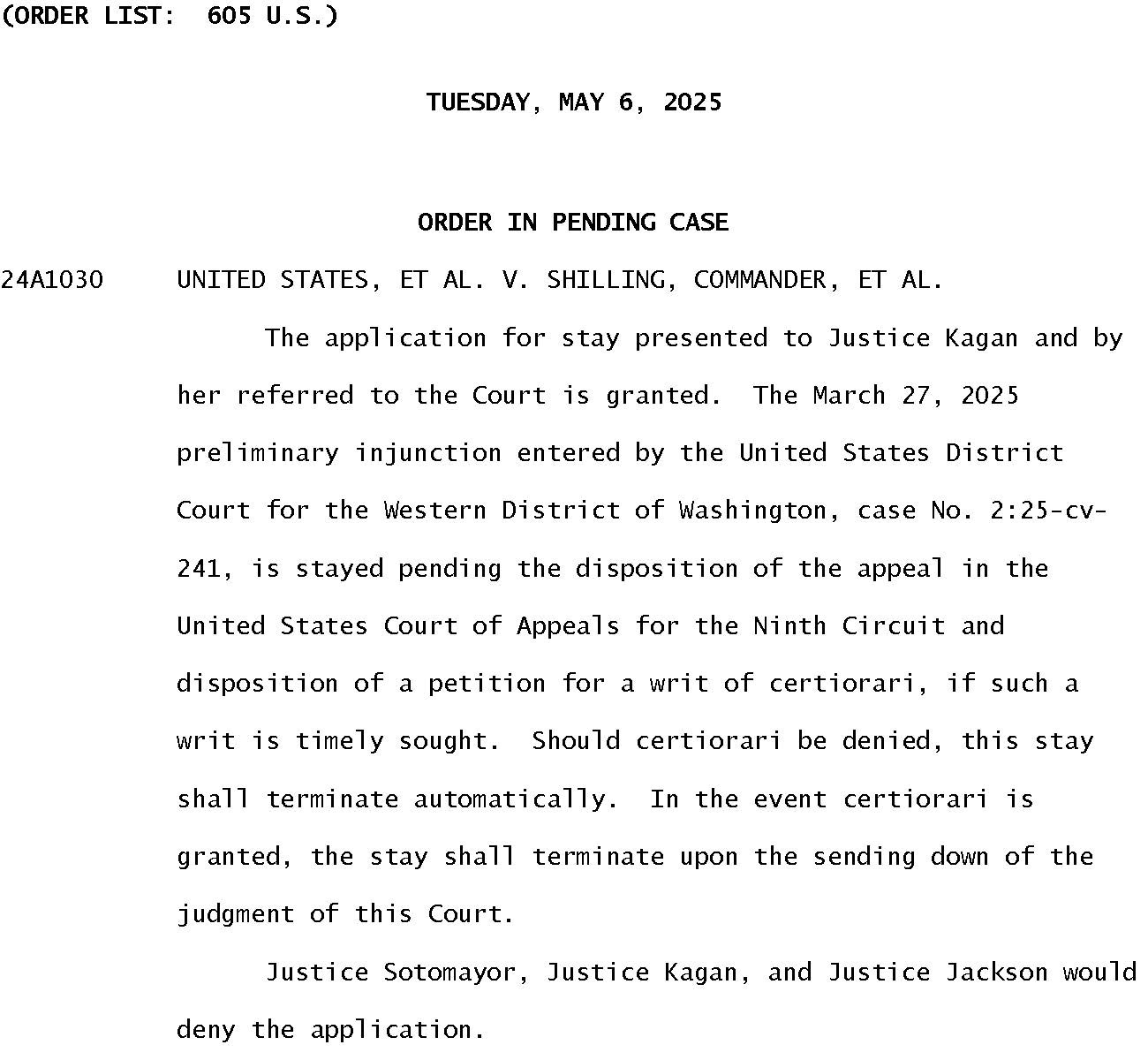

Monday’s unexplained ruling in the Department of Education downsizing case, about which I wrote Monday afternoon, has helped to provoke long-overdue attention to the justices’ unwillingness to explain many (if not most) of their grants of emergency relief. I wrote a few weeks back, in the context of the third-country removals case, about why it was so important for the Court to be explaining its rulings—both in the abstract and in the specific context of its repeated interventions in favor of the Trump administration.

But I thought I’d use today’s bonus issue for a related, but distinct, purpose: As ever, the Court has its defenders—even for actions that, to many, may seem indefensible. And that has extended to arguments for why the Court doesn’t need to explain itself. Below the fold, I take a stab at identifying all of the reasons I’ve heard or seen in support of the Court not writing—and why, although some of those arguments might make sense in some other cases, they rather fail to persuade when it comes to the (as of Monday, seven) entirely unexplained grants of emergency relief to President Trump.

For those who aren’t paid subscribers, we’ll be back (no later than) Monday with our regular coverage of the Court. For those who are, please read on.

Argument #1: We Haven’t Written Before

One argument I’ve heard is that writing just isn’t the “norm” when it comes to grants of emergency applications. Historically, at least, that wasn’t true. Up until 1980, when the norm was that almost every emergency application was resolved by the relevant circuit justice, there were tons of examples not only of in-chambers opinions by circuit justices respecting applications, but also in-chambers arguments. It was only when the Court in the early 1980s quietly shifted to referring all potentially divisive applications to the full Court that the norm of not writing (and not holding oral argument) hardened. Even then, throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, almost all of the full Court’s unexplained grants of emergency relief were with respect to impending executions—where, however important the Court’s individual rulings may have been, they tended to not produce statewide or nationwide policy effects.

Instead, it was only starting with the 5-4 February 2016 ruling blocking President Obama’s Clean Power Plan, and a flurry of rulings during the first Trump administration, that we saw a real uptick in full Court grants of emergency relief in cases with potentially nationwide consequences that usually came with no substantive explanation. So if the claim is that “the Court didn’t always write respecting grants of emergency relief during the first Trump administration,” that’s true so far as it goes (of course, the Court still wrote in some of those cases), but it totally hides the ball about how much of a departure those cases were.

Argument #2: There’s No Need For an Explanation

The gist of this argument, insofar as I understand it, is that it’s so transparently obvious why the justices are granting emergency relief that any explanation would be superfluous.

Even without multiple recent examples to the contrary, this argument strikes me as spurious. Assuming the justices are following the traditional criteria for granting emergency relief (and, if they’re not, how is that supposed to be obvious?), there is so much play in the joint in these cases. Consider Monday’s grant of a stay in the Department of Education downsizing case. The Trump administration made three very different arguments about why it’s likely to prevail on its appeal—one about standing; one about subject-matter jurisdiction; and one about the merits. What part of the boilerplate language the majority employed tells us which of those defects was decisive?

Or, if you prefer, consider the third-country removals case, where the Court’s unexplained stay of the district court’s injunction against third-country removals without certain procedural safeguards raised so many questions about its scope that the Trump administration had to come back to the justices and seek clarification of what they had meant? I don’t doubt for a moment that there are smart, savvy observers who can come up with plausible explanations for the Court’s unexplained orders in many—if not most—of these cases. But the notion that the explanations are sufficiently self-evident so as to obviate the need for the justices to articulate them is utterly belied by multiple, recent examples to the contrary.1

Finally, one variation is that there’s “no need” for explanations not because the rulings are self-evident, but because they’re ephemeral. But that argument, in my view, runs into two different problems. First, it whitewashes the significant consequences these rulings are creating—bells, in many of these cases, that will be almost impossible to un-ring. The need for written explanations when the Court grants emergency relief is not because the Court is conclusively resolving an important legal question (more on this point below), but so it can rationalize a ruling that’s producing massive (and, for many, massively harmful) real-world effects. The potentially finite duration of the ruling doesn’t negate those effects.

Second, and in any event, if the purpose of these interventions is, as Justice Kavanaugh suggested in his CASA concurrence, to provide a “nationally uniform” rule to govern the country while these cases work their way through the courts, an unexplained order just … can’t do that, especially when it’s possible that the reason for the Court’s intervention is specific to the plaintiffs in that particular case—versus some general conclusion about the lawfulness of what the government is doing. If Monday’s stay in the Department of Education case reflected a conclusion that these plaintiffs lack standing at this juncture, other plaintiffs would be free to bring their own claims in other cases. If it instead reflected a conclusion that everything the Department is doing is lawful, well, that would be a different matter, entirely. There’s just no way to know which is which without at least some input from the majority.

Argument #3: There Isn’t Enough Time to Write

Another argument I often hear about why the Court can’t be expected to write in these cases is because they are “emergency” applications, and so the Court just doesn’t have time to write a meaningful opinion.

In death penalty cases, when emergency applications often reach the Court with an execution date (and time) rapidly approaching, there’s at least some purchase to this argument (although a temporary stay of execution could solve that problem). But for better or worse (my own view is the latter), the Court has gotten almost entirely out of the business of granting last-minute stays of execution, so this concern is a bit of a red herring. Election cases may be a better example—especially those that reach the Court within weeks, or days, of an impending election. Fortunately, those come, at most, every two years.

None of the Trump-related cases, in contrast, have been either death penalty or election cases with that kind of running clock—where there is a hard-and-fast deadline that the Court has to meet.2 Indeed, if we take the 18 rulings the Court has handed down to date on emergency applications from the Trump administration, the average time from filing to decision has been 24.4 days. Even if we take the birthright citizenship decision out of the data set (since it was set for argument), the average time from filing to decision for the other 17 rulings is still 19.6 days (and it’s going up by the day). Nearly three weeks is plenty of time to write … something.

Don’t just take my word for it; in the TikTok case earlier this term, the Court handed down a 20-page majority opinion just one week after oral argument, and two weeks after briefing was complete. And, excluding the birthright citizenship cases again, for the two other Trump applications for which the Court did write majority opinions, the rulings came down nine and 10 days, respectively, after the applications were filed. The Court has plenty of time to write in these cases—if it chooses to do so.

Argument #4: Writing Requires the Court to Take a Position

In my view, this argument tells on itself, for the Court should not be granting emergency relief without at least some interim assessment, by a majority of justices, of the factors for granting emergency relief. That position can be a revocable one (more on that below), but the argument that the Court should be free to grant a stay without reasons it is willing to commit to writing is an argument for exercises of fiat, not judicial power.

What’s more, if the Court is properly applying the settled standards for emergency relief, a stay does not require the justices to take a conclusive view on the merits. Rather, “likelihood of success on the merits” is just one of the four factors that’s supposed to guide whether or not to provide such interim relief. It seems entirely obvious that a principled jurist could be profoundly torn on the merits, and still think emergency relief is appropriate because of the (im)balance of the equities. Here, again, the argument against writing seems inextricably intertwined with the disappearance of proper equities balancing from these cases. In point of fact, courts that are properly articulating and applying the factors for emergency relief often do not need to take a position on the merits of a dispute—and certainly not a conclusive one.

One variation on this argument is the possibility that, although a majority of justices favor granting emergency relief, they don’t all agree on the reasoning—and so providing a single, controlling rationale isn’t viable. Of course, this doesn’t stop the Court on the merits docket; we see plenty of cases in which the justices file only a “plurality” opinion in support of a judgment. It’s not clear why the same couldn’t happen with respect to an emergency application—“Justices A, B, and C note that they believe the government is likely to prevail on the merits because X; Justices D and E note that they believe the government is likely to prevail on the merits because Y.” It’s messy, but it’s a heck of a lot more (useful) information than writing nothing at all.

Argument #5: Writing Locks the Court in on the Merits

The only justice who has publicly engaged with the debate over whether the Court should be providing explanations for grants of emergency relief is Justice Kavanaugh—who briefly touched on the issue in his separate opinion concurring in the unexplained April 2024 stay that put Idaho’s ban on gender-affirming medical care for transgender adolescents back into effect. In his words:

A written opinion by this Court assessing likelihood of success on the merits at a preliminary stage can create a lock-in effect because of the opinion’s potential vertical precedential effect (de jure or de facto), which can thereby predetermine the case’s outcome in the proceedings in the lower courts and hamper percolation across other lower courts on the underlying merits question.

In the very next sentence, Kavanaugh noted that this is also a concern even when the Court doesn’t write. And his CASA concurrence, which argues that the Court should often provide a “nationally uniform” interim rule, seems flatly inconsistent with this passage.

But even taking it at face value, again, this concern is principally a byproduct of the Court’s continuing failure to properly conduct equities-balancing analysis. If the Court writes an opinion that says “we think it’s a very close call on the merits, but the equities tilt so decisively in favor of the applicant that we’re granting a stay,” then no objective lower-court judge could read that ruling as “predetermin[ing] the case’s outcome” and “hamper[ing] percolation.”

What’s more, lower-court judges well know something that Justice Kavanaugh has apparently forgotten—that there are multiple recent examples in which the Court stayed an injunction that it then affirmed on plenary review (for instance, the Alabama redistricting cases—where the justice who changed sides was … Kavanaugh); or refused to stay an injunction that it then reversed on plenary review (for instance, in two Biden-era immigration cases—Biden v. Texas and United States v. Texas). Would writing opinions respecting the stays in those cases have precluded the Court from reaching different results on plenary review? It’s hard to imagine that the answer is “yes.” Indeed, in the Alabama redistricting cases, the only justice who voted for a stay and wrote to explain his vote was … Justice Kavanaugh.

Argument #6: Fast Opinions are Sloppy/Shoddy Opinions

Another argument I’ve heard is that the Court is not at its best when it is moving quickly. This strikes me as undoubtedly true as an historical claim, but also mostly a non-sequitur here. As I suggested above, the Court can provide itself with all the time it needs to write in these cases—especially if it’s really throwing the equities to the wind.

But even if the Court is rushing to meet some arbitrary deadline, again, it seems critical to distinguish between the very different questions of whether the Court should write and what the Court should say. Consider the two Trump applications that have been granted with majority opinions but without oral argument—the Department of Education teacher training grants case; and the J.G.G. Alien Enemies Act case. Both majority opinions are quite short. Both take at least an interim position on complicated procedural questions that have produced a ton of case law (and confusion) in the lower courts—about which monetary claims have to be brought in the Court of Federal Claims in Department of Education; and about when migrants’ challenges to their impending removals have to be brought through habeas petitions rather than claims under the Administrative Procedure Act.

Whether or not you buy the Court’s … brief … analyses of these points (more on that below), my own view is that we’re much better off with them than without them. Although I believe that both cases should have come out the other way, if the Court was going to grant stays in both cases, the (brief) guidance it provided to lower courts and to the parties was critical. Consider, especially, the guidance the Court provided in J.G.G.—not only that migrants had to challenge Alien Enemies Act removals through habeas petitions, but that they were entitled to notice and a meaningful opportunity to object before they could be removed. It was that passage that provided the basis for the Court’s subsequent intervention in the A.A.R.P. case—when it looked like the Trump administration was about to flout that mandate. Had the Court written nothing, the Alien Enemies Act cases might have played out very differently—and not at all for the better.

Argument #7: Be Careful What You Wish For…

That last point segues to this one—which is an argument I often hear from folks generally less sympathetic to the Court (and the Trump administration). If the Court is going to end up in the wrong place, anyway, aren’t we better off if it doesn’t write? Put another way, as between an unsigned, unexplained order and a five-page opinion that makes a hash out of some important question of federal statutory or constitutional law, shouldn’t we prefer the former?

From a purely political perspective, it’s easy to see why the answer ought to be “yes.” An unexplained order does less short- or long-term violence to doctrine than a poorly explained order—like how the Court’s explanation for the stay in Trump v. Wilcox all-but inters Humphrey’s Executor, when an unexplained stay might not have.

That said, it strikes me that there are two problems with this response—one small, and one massive.

The small problem is the assumption that the writing will lead to doctrinal violence. As my judge used to tell me when I was clerking, sometimes, you won’t really know how well a legal argument works until you write it out—because there are some claims that “just won’t write.” If the Court having to write prompts it to reconsider even a tiny minority of its rulings in these cases, that seems like a price worth paying. If it “just won’t write” and the Court writes it anyway, that, too, seems better to have out there.

The larger problem with this reaction is how it wholly neglects the institutionalist perspective. Far more important than the state of individual doctrines is the state (and public credibility) of the Court. Individual grants of emergency relief without explanations may not imperil that credibility—especially when their effects are modest and/or when the Court appears to be speaking in one voice. But when the Court is granting emergency relief over and over again in a manner that is clearing the way for some of the most aggressive exercises of executive power that we’ve ever seen; when at least some of those rulings appear outwardly inconsistent with how the Court handled superficially comparable requests from the Biden administration; when it’s doing so in cases in which the government has openly defied lower courts; and when the three Democratic appointees are all (loudly) dissenting; the majority’s failure to provide rationales for its interventions risks doing serious damage to the Court’s public credibility—at a time when it may need that credibility more than at any other moment in its modern history.

Coming to terms with Supreme Court decisions that create problematic doctrine seems to me, to quote Hyman Roth, “the business we’ve chosen.” Coming to terms with a Court that won’t explain itself as it enables some of the most lawless behavior in the history of the American presidency just … isn’t, and shouldn’t be. The point is not that there are no costs to writing majority opinions in those cases. The point on which I would’ve thought everyone could agree is that those costs are dramatically outweighed by the serious and steadily mounting costs of a Court that is not explaining itself—not just the costs to those who are directly and indirectly affected by these rulings, but the costs it is increasingly imposing upon itself.

We’ll be back (no later than) Monday with our next regular issue of “One First,” which, I can promise, will not be unexplained. Until then, thank you for your continued support of this newsletter—and I hope you and yours are staying safe out there.

Nor can the (often lengthy) dissenting opinions in these cases be used as conclusive proof of what the majority meant. Consider, again, the third-country removals case. When the Court granted a stay of a district court’s injunction with no explanation on June 23, Justice Sotomayor’s dissent specifically disclaimed that the ruling applied to the district court’s subsequent remedial order. But the majority subsequently clarified that it did.

One might also point out, insofar as the Court has given short shrift to the irreparable harm analyses in these cases, that without some assessment of the harm being caused by the lower-court rulings at issue, it’s not clear why the Court should be in such a hurry to decide any of these disputes.

Argument number infinity (sadly missed by Prof. Vladeck), "We are fascists in black robes and accountable to nobody with the possible exception of the adjudicated rapist and convicted felon in the White House."

The heart of the matter is quite clear here. Karl Marx once wrote "Principles are what you impose on the other side, so that you may maneuver more freely." The demands of power shift constantly. To pretend to principle through explanation is to impose limits on such maneuvering. The Court has no intention of so limiting its powers in this manner. The Court has repeatedly violated precedent, and will continue to do so as it jettisons its Constitutional role as a separate branch of government for its purpose as an eager partner in the transformation of American society into that envisioned by the alliance of theocrats and plutocrats that form the core of American fascism. This Court has long been the advance guard of such a transformation.