169. Emergency Orders as Precedents

Wednesday's ruling in Boyle isn't the first time the Court has given precedential effect to an unsigned order, but it's the first time it tried to explain *why,* for reasons that ... fail to persuade.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); and we’ll usually have a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current issues, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

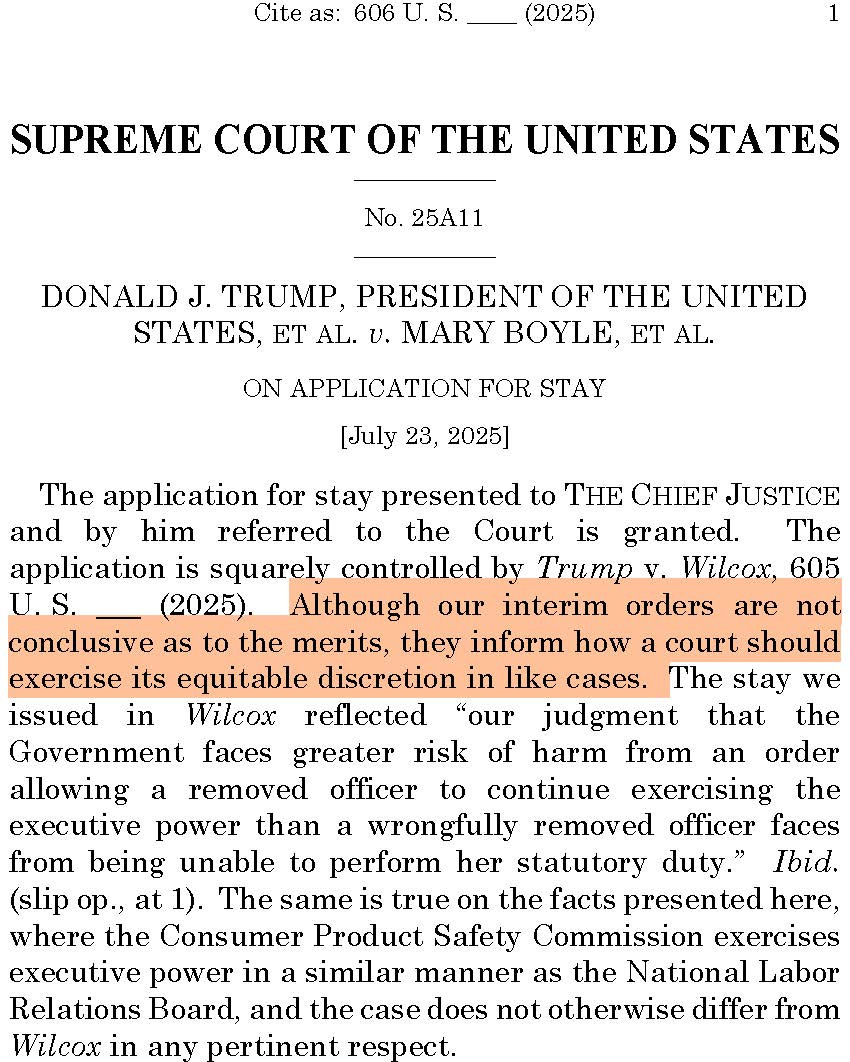

The biggest news the Supreme Court made last week was Wednesday’s brief order in Trump v. Boyle granting yet another emergency application by the Trump administration—this time, to clear the way for the President to remove the three Democratic members of the Consumer Safety Product Commission despite a statute that bars their removal without good cause. The analytical significance of the Court’s ruling is both in treating the Court’s prior order in the Wilcox case as a precedent that lower courts should have followed in this case, and in briefly asserting a reason for why:

As I explain below the fold, there is a serious analytical flaw in the Court’s “logic”—one that is compounded by the fact that, in many of these cases, the justices are providing even less of an explanation than the cryptic May 22 order in Wilcox had. Against that backdrop, the Court is asking lower courts not just to treat its unexplained (or thinly explained) orders on emergency applications as precedents, but to do so in contexts in which lower courts have to guess as to exactly why the justices granted emergency relief in the prior case. To spoil the punchline, whether a case is a “like” case, and whether it “differ[s] from” a prior case “in any pertinent respect,” will often be in the eye of the beholder—as the lower-court rulings in Boyle itself illustrate.

Indeed, neither the district court nor the Fourth Circuit in Boyle ignored Wilcox; they both distinguished it—on entirely plausible grounds. If the justices in the majority want lower courts to treat its rulings as precedential, then they need to say much more about why they’re granting emergency relief in the first place—entirely so that lower courts will know which apparent distinctions among cases are material, and which ones aren’t. Indeed, that’s how legal analysis … works. Telling lower courts that even grants of emergency relief without such clarity are nevertheless precedential, in contrast, is the very definition of chutzpah—and not just because it contradicts what some of the same justices have previously insisted.

But first, the (other) news.

On the Docket

As expected, the Court on Monday issued the first of three summer housekeeping order lists—this time comprising 21 denials, without any explanation or noted dissents, of petitions for rehearing.

Wednesday afternoon brought with it the grant of the Trump administration’s emergency application in the Consumer Product Safety Commission case, about which I’ll have much more to say below. And Thursday, over public dissents from Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch, the full Court stayed the Eighth Circuit’s mandate in the North Dakota Voting Rights Act case I mentioned last week (in which Justice Kavanaugh had already issued an administrative stay). Among other things, that signals a very strong chance that the Court will take the case up for plenary review (on whether the Voting Rights Act’s central provision can be enforced by private plaintiffs, or just the federal government).

That was it for the full Court last week. But Justice Kagan also made headlines on Friday in remarks at the Ninth Circuit Judicial Conference in Monterey—for which there is, believe it or not, video(!) Among other things, Justice Kagan offered a series of sharply-worded critiques about how the Court has been handling emergency applications, especially the pattern of granting relief with little or no explanation. Given how deliberately Justice Kagan picks her spots, these comments seem quite carefully calibrated—and worth hearing/reading.

And in one curious note, in a lawsuit filed by the right-wing America First Legal Foundation against the Judicial Conference of the United States, and Chief Justice Roberts in his capacity as its head (attempting to use FOIA to obtain various communications that allegedly exist between the AO and members of Congress respecting Justices Thomas and Alito), a motion to dismiss was filed last week not by the Department of Justice, but by Ethan Torrey, who is identified in the pleading as “Legal Counsel” to the Supreme Court. The justices, the Court, and even the Judicial Conference have all been sued before. But I don’t recall a prior suit like this in which those defendants were not represented by the Department of Justice. Unless my memory is just faulty (which is a distinct possibility), that raises the question of whether DOJ declined to represent the defendants in this case—or whether the Chief Justice never even asked. If this is a departure from the norm, it’s a fascinating (and potentially telling) one.

Turning to this week, nothing formal is on the calendar, but the Court is likely to be busy yet again with a slew of emergency applications. On Thursday, the Trump administration filed its 21st emergency application—this time seeking to allow it to continue to withhold funding for roughly 800 NIH grants, which the government claims it paused because the grants involve politically sensitive topics. Justice Jackson ordered the plaintiffs in the two (partially consolidated) cases to respond to the application by 4 p.m. (ET) this Friday, so it’s unlikely we’ll get a ruling this week.

A ruling this week is more likely on a pair of emergency applications from death row inmates—one in Tennessee and one in Florida. And the Court also has before it a significant new emergency application from NetChoice (the same organization whose challenges to Florida’s and Texas’s social media content moderation laws were resolved by the Court last term). Specifically, NetChoice is challenging a Mississippi law that requires social media sites to verify the ages of its users (note that the Mississippi law is significantly broader than the Texas law requiring age verification for adult websites, which the justices just upheld against a First Amendment challenge). The district court had enjoined the Mississippi law, but the Fifth Circuit issued an unsigned, unexplained order staying that injunction—and NetChoice is asking the justices to put the injunction back into effect. Justice Alito has ordered Mississippi to respond by 4:00 p.m. ET on Wednesday.

The One First “Long Read”:

Precedent on the Shadow Docket

Speaking of Justice Alito, folks might remember that in September 2021, Alito gave a lengthy speech at Notre Dame Law School in response to then-emerging criticisms of how the justices were handling emergency applications. In his speech, Alito purported to describe each of the critiques of the Court’s behavior (he missed a few, and some of the others were strawmen). But he specifically addressed concerns raised by me (and others) about the Court starting to treat some of its unsigned, unexplained orders as precedential—stressing that “a ruling on an emergency application is not a precedent.”

By that point, we had at least a handful of examples to the contrary—and not just in the small minority of cases in which the Court deigned to write a majority opinion. Whatever else might be said about such opinions, it seems to me relatively uncontroversial that when the justices file an opinion of the Court that includes legal analysis in it, that analysis can (and should) be precedential at least for the purposes for which it was deployed.1

But as I explained in detail in Chapter 5 of The Shadow Docket, in a case known as South Bay II decided late on a Friday night in February 2021, the Court granted emergency relief to block California’s COVID-based restrictions on indoor religious worship services without a majority opinion (or any reasoning at all in the majority’s brief order). Shortly thereafter, it started treating South Bay II as a precedent that lower courts were bound to follow. To that end, several lower court rulings were “GVR’d” (granting certiorari, vacating the decision below, and remanding for reconsideration) in light of South Bay II. And in a case known as Gateway City Church, in which the district court and Ninth Circuit had refused to block Santa Clara County’s different restrictions, the Court concluded that “The Ninth Circuit’s failure to grant relief was erroneous” because “this outcome is clearly dictated by this Court’s decision” in South Bay II.

The Court never explained how an unexplained order could “clearly dictate[]” the result in a different case about a different government’s different COVID restrictions; it simply asserted it as a fact. But whatever the justification, what couldn’t be denied is that, for what appeared to be the first time, the Court had directly invoked an unexplained grant of emergency relief as a ruling that was entitled to precedential effect in lower courts—whose failure to abide by that ruling would itself constitute reversible error.2

Fast-forward to Wednesday’s ruling in Boyle. As I noted above, both the district court and the Fourth Circuit had the benefit of the Supreme Court’s brief May 22 order in Wilcox. The district court had even relied upon Wilcox’s assessment of the equities to justify denying a preliminary injunction to the plaintiffs—only to conclude that they were ultimately entitled to permanent injunctive relief. And Judge Wynn’s opinion concurring in the Fourth Circuit’s denial of a stay devotes the better part of two pages to explaining why the Supreme Court’s intervention in Wilcox didn’t compel a different result. Obviously, a majority of justices disagree with them—and that is their right. But the notion that the lower courts were somehow indisputably bound by what little the Supreme Court said in Wilcox is belied by that record, and by the paucity of reasoning in Wilcox itself, as Justice Kagan pointed out in her short but sharply worded dissenting opinion (which was joined in full by Justices Sotomayor and Jackson).

Separate from whether the lower courts in Boyle were bound by Wilcox, there’s the more general statement by the majority in Boyle (which is sure to be cited over and over again by the Trump administration going forward) that “our interim orders . . . inform how a court should exercise its equitable discretion in like cases.”

The problem here is two-fold. First, and most obviously, many of the Court’s interim orders have even less discussion and analysis than the brief order in Wilcox. As I’ve noted before, there have been seven grants of emergency relief to the Trump administration since May 6 with no explanation whatsoever. In those cases, how is a lower court supposed to ascertain whether a case really is “like”? Even two cases that raises a superficially similar challenge (e.g., to a funding cutoff) may turn on very different procedural issues (such as standing; subject-matter jurisdiction; or the appropriate forum) that vary because of who the plaintiffs are or where the case was filed. If lower courts don’t know whether the justices granted emergency relief because they thought one particular set of plaintiffs lacked standing versus because they thought the underlying government action is legal, how in the universe are they supposed to figure out whether the cases are “like”? Different plaintiffs could easily overcome the standing problem in the first case; they’d obviously have a much harder time if the reason for the justices’ intervention was agreement with the government on the merits. So how is the next lower court to know whether the case in front of them is or isn’t “like”? I’ve written before about why the Court needs to provide more thorough explanations in these cases; this is worse—it’s the Court not only not providing those explanations, but refusing to accept what should be the most natural consequence of its failure to do so, i.e., that its unexplained orders are entitled to no precedential effect.

Second, even when the Court is providing at least a modicum of explanation, it is almost never taking the traditional standards for equitable relief seriously. I’ve become a bit of a broken record about all of the ways in which the Supreme Court has grossly distorted the irreparable harm analysis in these cases. What’s critical for these purposes is that it has done so without ever explaining what it is doing—so that lower courts are still beholden to the traditional factors as they are traditionally supposed to be applied. The result is that lower courts acting in the best of faith could look at a new case that is “like” one in which the Supreme Court previously granted emergency relief, apply the traditional equitable factors appropriately, and still be at odds with the justices because the justices aren’t doing so. That is hardly the lower courts’ fault; it is, like many other things, traceable directly to the justices’ refusal to take the traditional equitable criteria seriously or explain that (or why) they’re not doing so.

This, then, is the trap that Boyle springs on lower-court judges. In deciding whether to issue equitable relief and/or a stay of equitable relief already provided, lower-court judges are now instructed to try to fit a square peg into a round hole. They must decide whether the case before them is sufficiently “like” one in which the Supreme Court has already granted relief notwithstanding that the Court (1) may well have not explained itself in the earlier cases; or (2) explained itself in a way that doesn’t line up with the traditional standards for equitable relief. That’s hubris on the Supreme Court’s part; and it’s going to lead to all kinds of arguments from the government about what the justices must have meant in a prior decision—not what they actually said.

Even more significantly, such an approach takes the justices off the hook—because they can continue to not provide full-throated explanations of their interventions in these cases while also expecting that those interventions will produce effects in the lower courts in other cases. In essence, the Court gets to have its cake and eat it, too. It should be one or the other—if the Court wants to create precedent, it needs to fully explain its reasoning. And if it doesn’t, its rulings, whatever effects they have in individual cases, should have no effects elsewhere.

And although the Court may have the raw power to act this way, it is a development that is not only going to further fray the already deteriorating relationship between the Supreme Court and lower federal courts; it is also going to raise serious questions about how the Supreme Court generates precedent in the first place—and why those precedents bind not just lower courts, but other actors, as well. Because the kind of precedent Boyle is describing isn’t precedent at all; it’s just vibes.

SCOTUS Trivia: A Record-Breaking Emergency Docket

The North Dakota Voting Rights Act case (in which the justices granted a stay of the Eighth Circuit’s mandate on Thursday) was the 25th case in which the justices have granted emergency relief during the October 2024 Term. That number is a new record for total grants of emergency relief by the Supreme Court in a single term. According to my data, the previous record was 24 grants of emergency relief—during the wild (and COVID-influenced) October 2020 Term.

And speaking of records, the Court is on the verge of setting another one relating to emergency applications: The ruling in the North Dakota case was the 116th ruling by the full Court on an emergency application so far this term. The only other term in the Court’s history with more than 100 such rulings was last term (OT2023), when the Court handed down 122 of them. With more than two months left in OT2024, that record is also going to get shattered.

Folks will differ in their explanations for why the emergency docket is so busy. What can’t be denied at this point is that it is busier than it has ever been before—and that there’s every reason to think that this phenomenon is not ephemeral.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one!

This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday. Have a great week, all!

Law professors tend to talk about two kinds of precedent—“horizontal” stare decisis (when a court’s rulings bind it going forward); and “vertical” stare decisis (when an appellate court’s rulings bind lower courts going forward). For these purposes, I’m principally interested in (and focused on) the latter type of precedent. Indeed, as I’ve argued at some length, proper analysis of an emergency application should seldom create horizontal precedent—since the justices are (or should be, anyway) asking and answering different questions at that stage than they would be on plenary review.

A colleague once suggested that it’s possible to add together the different opinions by the justices in the majority in South Bay II to almost get to a majority rationale. Even if adding up concurrences in an order was a way to identify a majority rationale as opposed to a majority result (and I don’t think that’s a fair reading of the so-called “Marks” rule), the problem is that the three separate opinions not labeled as dissents—Chief Justice Roberts’s concurrence; Justice Barrett’s concurrence; and Justice Gorsuch’s “statement”—largely address different points or reach different conclusions.

First, the OIP (DoJ branch for FOIA) is without a Director and I cannot find information on the Acting Director. DOGE was also Freedom From Information, seems. If I had to guess, CJ Roberts either has no faith in the remaining staff, OR the acting leadership has a Conflict of Interest with Amerika Erste/America First and Roberts doesn't want another COI headache to give Democrats more fuel.

Second, I know I am not judicial material because I'd react to "unsigned, no opinion, emergency docket orders as precedent" with extreme sarcasm. I'd base my decisions on the number of left-handers among the parties, even-vs-odd numbers of Presbyterians, etc. as a total mockery of the process. If I were a Supreme, though...I'd save such questions for oral arguments, to mock Alito to his face.

Why do you think the dissenters aren’t making these points in dissenting from the orders? I know Justice Kagan has spoken about the lack of explanation elsewhere, and her dissent in Boyle talks about accumulating executive power, but I can’t remember any dissent lately that points to the impossible task these orders give the lower courts. Is this just a matter of them holding their fire? And if so, for what?