204. Accountability After Minneapolis

A short post explaining (1) why it's so hard to hold federal officers and/or the federal government liable for violating our rights; and (2) how a one-sentence statute could (and *SHOULD*) fix it.

For the second time in 17 days, federal law enforcement officers in Minneapolis, while purporting to carry out “immigration enforcement,” have shot and killed an American citizen (not that it would be any different if the victim were a non-citizen). Just like the killing of Renée Good on January 7 (and so much else of what federal officers are doing in and around the Twin Cities and elsewhere under the guise of law enforcement), Saturday morning’s shooting of a man multiple media organizations have identified as Alex Jeffrey Pretti once again raises the question of why it is so damned difficult to hold federal officers—and the federal government itself—accountable if and when they violate our rights.

Across various, wonkier issues of this newsletter, I’ve tried to provide the background and some introduction to how we got here:

How the Supreme Court in 1882 embraced a much broader view of the federal government’s sovereign immunity than the text of the Constitution supports;

How, instead, we relied upon deeply imperfect bodies of state tort law to hold individual officers accountable, even after Congress, in 1946, finally authorized a very limited class of tort suits against the federal government directly;

How the Supreme Court briefly (and, in my view, correctly) authorized federal suits against federal officers in 1971, only to spend the last four decades all-but-overruling that case (Bivens) on increasingly disingenuous grounds (for a shorter version of this last point, see this post);

And how Congress, in 1988, cut off many (if not most) state tort suits against federal officers by converting them into suits under that 1946 statute (the Federal Tort Claims Act)—even if the FTCA claim wasn’t/isn’t viable.

As this capsule summary suggests, although not all of the blame belongs to the Supreme Court, much of it does. And although the Court has attempted to sell its hostility to damages suits against federal officers on the ground that courts need Congress to authorize those suits, (1) that’s never stopped the same justices from endorsing the power of federal courts to issue injunctions against federal officers without specific statutory authorization; and (2) as Justice Harlan put it in Bivens,

it would be at least anomalous to conclude that the federal judiciary . . . is powerless to accord a damages remedy to vindicate social policies which, by virtue of their inclusion in the Constitution, are aimed predominantly at restraining the Government as an instrument of the popular will.

In other words, it would be pretty dumb to hold that the government has to affirmatively authorize any remedies to enforce a Constitution designed to constrain the government.

I wanted to write this afternoon both because writing is how I cope with the increasingly distressing shape of events and because it seems worth making four points as loudly as possible:

First, meaningful accountability for government officers isn’t—and shouldn’t be—a political or ideological issue. One can accept that we’re all going to have widely varying views on exactly which rights the Constitution protects (and how), and still believe that, whatever rights the Constitution recognizes, there ought to be a meaningful way to enforce them against all government officers. Otherwise, what’s the point of having those rights in the first place? A world in which the Constitution is only enforceable against the federal government prospectively is a world in which the federal government and its officers can do whatever it wants to the people—so long as the misconduct is brief and fleeting. This is why, for instance, it has proven so much easier to enforce the Second Amendment (where government restrictions are creating forward-looking consequences) than the Fourth (where the violation is usually a one-off).

Second, under current law, it is difficult—but, contra Vice President Vance, Stephen Miller, and lots of other people, it is not impossible—to attempt to use civil and state criminal remedies to hold federal officers accountable if and when they do violate our constitutional rights. I’ve written before about “Supremacy Clause immunity,” which is what would come into play if state or local officials attempted to prosecute a federal officer for crimes committed while on their federal job. But there’s also a narrow avenue that the Supreme Court has never foreclosed to potential damages liability—where the plaintiff brings a state tort claim to vindicate their constitutional rights, a claim that arguably falls within an exception to that 1988 statute that otherwise converts those claims into (very-hard-to-win) Federal Tort Claims Act claims against the federal government (there’s more on this very legalistic point in the footnote at the end of this sentence).1 It seems to me that these approaches are increasingly worth attempting notwithstanding their long odds—because, again, what’s the alternative? That brings me to…

Third, it would take a Congress that actually thought federal officers should be liable for violating our constitutional rights about a one-sentence statute to fix the accountability gap that I (and plenty of others) have long documented. Indeed, there are various bills already pending that would be solid steps in the right direction.2 Across all of the federal accountability controveries of my professional career—torture; warrantless wiretapping; the unlawful surveillance programs leaked by Edward Snowden; drone strikes on U.S. citiziens; the George Floyd protests; and on and on—it has boggled my mind that there isn’t bipartisan support for such legislation. And, although this may lead readers to call me “partisan,” it’s worth stressing that, at virtually every turn, the reason why these legislative proposals haven’t advanced has invariably been opposition from Republicans—not Democrats.3

Fourth, and speaking of my mind being boggled, I also continue to be more than a little disappointed in the small but significant cohort of visible, accomplished, and undeniably intelligent right-of-center law professors who have spent the last 17 days (and, really, the last 369) staying awfully quiet. I understand the reluctance to stick one’s neck out, especially in this current moment in our political culture. But it seems like this kind of reform—accountability for when federal officers break the law—is something folks should easily be able to get behind even if they’re unwilling to express a view on whether any of what sure looks like rampant lawlessness we’re seeing from this administration actually crosses the line. Again, meaningful remedies for constitutional violations ought to be something every single person can support—all the more so if their full-time job is preparing the next generation of lawyers and legal thinkers to come up in a system in which legal violations have at least the specter of producing meaningful consequences.

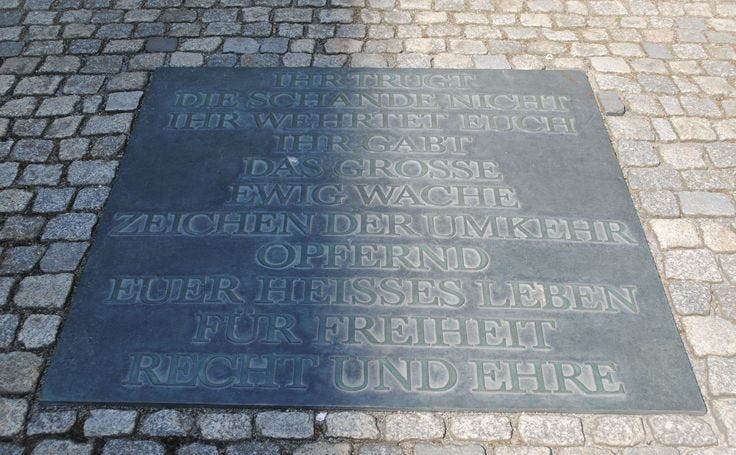

As longtime readers of this newsletter know, I spent a lot of time in college studying not just the violent crises of the twentieth century, but also the attmepts by legal and political systems to build an unassailable historical memory of those abuses—and, just as significantly, of those who fought to stop them. In that respect, the first image that came to my mind this morning when I learned about this latest Minneapolis shooting is a plaque that rests on the ground of the German Resistance Memorial Museum in Berlin—near the spot where Claus von Staffenburg and his co-conspirators were executed shortly after midnight on July 21, 1944 for their role in the attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler. The plaque, pictured below, is in German. But its message translates as:

You did not bear the shame.

You resisted.

You bestowed the eternally vigilant symbol of change by sacrificing your impassioned lives for freedom, justice and honor.

Hopefully, it will take us less time to realize the errors of our ways—and what ought to be a commonsense, low-hanging-fruit way to start ensuring meaningful accountability for those errors. It just shouldn’t be the case that the only way to hold the federal government accountable is to elect a new one.

If you’re not already a “One First” subscriber, I hope you’ll consider signing on.

Regardless, we’ll be back Monday with our regular coverage of the Supreme Court and related topics. I end each newsletter by exhorting folks to “stay safe out there.” That hits a little harder on this cold, sunny, and yet remarkably dark Saturday afternoon—but I mean it more than ever.

The full academic version of this argument is available here. For a shorter version from a Trump-appointed D.C. Circuit judge, see here.

There is a separate question about whether and to what extent federal officers should be allowed to invoke “qualified” immunity. But it seems like we ought to be able to agree that, especially when the violation of our rights is egregious and the wrongfulness is clearly established, there ought to be some redress.

Worse than that, when Congress finally passed a new cause of action late last year to allow suits against federal officers and/or the federal government for at least some alleged constitutional violations, the statute allowed only senators to sue—and even then, only for the allegedly wrongful collection of some of their phone records during the Arctic Frost investigation.

Sinclair Lewis (and others) have been quoted in the 1930’s as saying, “When fascism comes to America, it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross.” How in the world can we find ourselves in this situation now? Surely the people cannot be so foolish as to swallow the lies that are being spread by federal workers and elected or appointed officials.1/24/26

Thank you for posting this.