Bonus 197: Necessity, Legality, and the Rule of Law

December 18 is an ignominious anniversary for the rule of law in America—and an opportune moment to reflect upon the responsibility of lawyers and judges to distinguish between necessity and legality.

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter and other unscheduled issues will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, I put much of the weekly bonus issue behind a paywall as an added extra for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and I hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit (and/or consider giving a subscription as a gift this holiday season):

Today marks an especially ignominious anniversary for the Department of Justice—and for the Supreme Court. 81 years ago today, on Monday, December 18, 1944, the Supreme Court handed down its ruling in Korematsu v. United States, in which a 6-3 majority, in an opinion by Justice Hugo Black, rejected a constitutional challenge to a statute that made it a crime to violate an exclusion order—thereby validating much of the Japanese American internment program during World War II. I’ve written before about the full background to the internment cases, and also the other decision the Court handed down on December 18—Ex parte Endo, which, the story goes, was supposed to have closed the camps (and why it didn’t).

But I wanted to come back to this topic today because one of the real sins of internment wasn’t just the policy itself, but the affirmative misrepresentations about the need for the program that the government made to the Supreme Court in the course of briefing the internment cases—and the Court’s behavior, in turn, in relying upon them. Indeed, although he didn’t know at the time that the government was misrepresenting the facts, this was largely the point of Justice Jackson’s enigmatic dissent—that the problem in Korematsu wasn’t the internment policy itself, but the fact that a majority of the Court had gone out of its way to rationalize that policy to the Constitution.

The thread that ties these points together is the idea that there’s something qualitatively different—and, indeed, worse—for the rule of law when lawyers and judges attempt to retrofit legal rationales onto exigent measures that were, or were at least claimed to be, “necessary,” as compared to the exigent measures themselves. Lawyers and judges, the argument goes, bear special responsibility for distinguishing between necessity and legality. If I run a red light while driving a loved one to the emergency room, I can’t get out of the ticket just because I had a good reason for defying the law, and no lawyer or judge should conclude otherwise. Mitigation is a reason to reduce the penalty, not to rewrite the law.

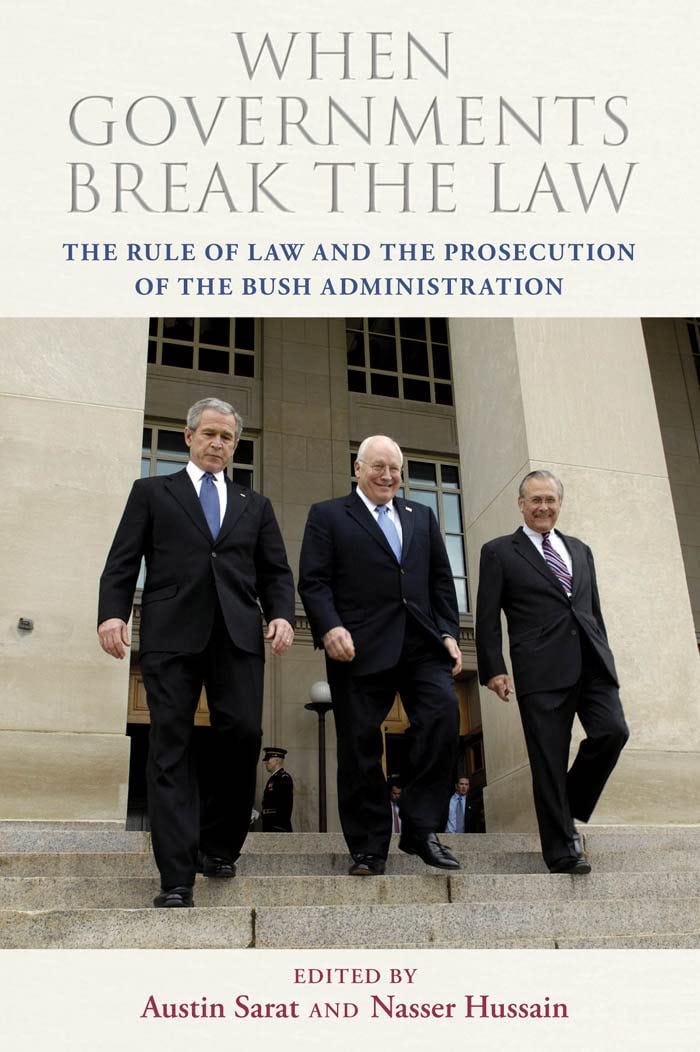

15 years ago, for a book titled “When Governments Break the Law: The Rule of Law and the Prosecution of the Bush Administration,” which was edited by Amherst College professors Austin Sarat and Nasser Hussain (the latter of whom was my undergraduate adviser and mentor), I wrote a lengthy chapter about the memory of internment and the lessons it provided for then-current debates over whether Bush administration lawyers should be held accountable for their role in providing legal justifications for the torture of enemy combatants after September 11. It’s one of the papers I struggled the most to write in my academic career—and of which I’m the proudest.

Given how much salience that chapter continues to have today, I thought it would be interesting to reprise it—and I do so below the fold. The upshot is two-fold: why that argument (that it’s worse when lawyers and judges rationalize bad actions) is absolutely right, and the importance of the formation of historical memory that unequivocally repudiates the legal arguments—and not just the lawless behavior itself. That happened for internment; it hasn’t happened to the same degree (yet) for post-9/11 torture.

For those who are not paid subscribers, we’ll be back (no later than) next Monday with more regular coverage of the Supreme Court. For those who are, please read on.