173. Justice Kavanaugh and the Equities

Thursday's ruling in the NetChoice case appears to suggest that one of the key justices is either being inconsistent or completely hypocritical in how he is voting on emergency applications.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to lawyers and non-lawyers alike. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current issues, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

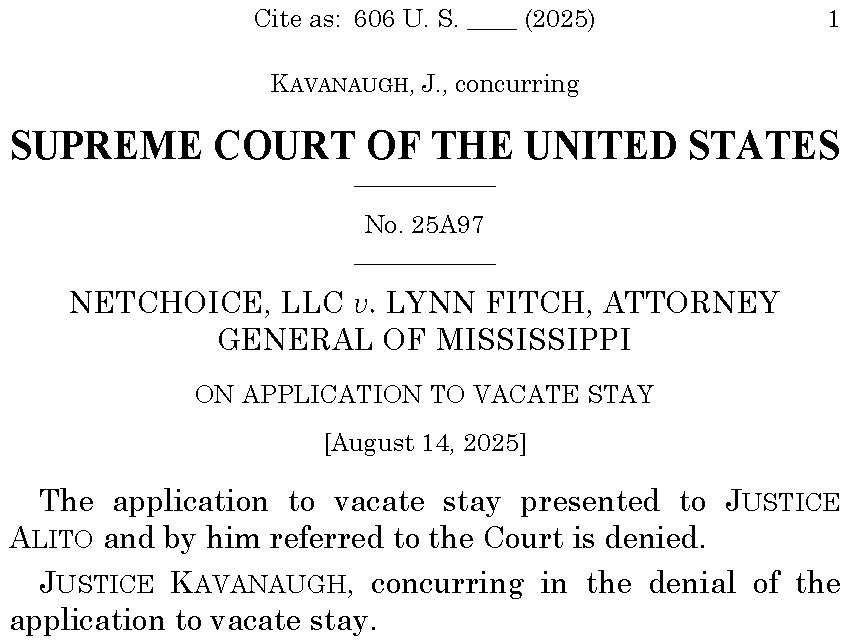

The full Court handed down a single ruling last week—denying NetChoice’s application to put back on hold a Mississippi law that requires social media websites to verify the ages of their users (and to obtain parental consent before allowing access to minors). The district court had blocked the law on the ground that it likely violates the First Amendment—because it requires Mississippians to hand over sensitive, personal data in order to access (and engage in) vast amounts of constitutionally protected speech. In an unsigned, unexplained order, the Fifth Circuit put that injunction on hold. And the Supreme Court on Thursday left the Fifth Circuit’s stay intact—without any majority rationale.

Instead, the only opinion was a brief concurrence from Justice Brett Kavanaugh. In it, Kavanaugh wrote that “NetChoice has, in my view, demonstrated that it is likely to succeed on the merits—namely, that enforcement of the Mississippi law would likely violate its members’ First Amendment rights under this Court’s precedents.” He nevertheless voted against vacating the Fifth Circuit’s stay because “NetChoice has not sufficiently demonstrated that the balance of harms and equities favors it at this time.”

As I explain below the fold, this brief statement is more than a little difficult to reconcile with both what Kavanaugh has said in prior opinions respecting emergency relief and how he (and four or five of his colleagues) have voted in many (if not most) of the emergency applications brought to date by the second Trump administration. Indeed, one of my biggest criticisms of those rulings has been their refusal to take the equities seriously—to focus entirely on whether the executive branch is likely to prevail on the merits. To rest on the equities here not only appears to be inconsistent with that approach; it’s also inconsistent with how the Court approached emergency applications from the Biden administration—in which, on three different occasions, it denied relief even though it ultimately sided with the executive branch on plenary review (that is, it denied relief seemingly because of the equities).

Ultimately, either the equities should matter or they shouldn’t. There is no analytically persuasive reason why they should matter only if the federal government is not a party. And there’s even less of a reason why they should matter only if the Trump administration isn’t involved.

But first, the (other) news.

On the Docket

As noted, the only ruling from the full Court last week was in the NetChoice case, about which (much) more below. But there were four other Court-adjacent things that I wanted to flag.

First, on Tuesday, the Court (finally) released the oral argument calendars for the October 2025 and November 2025 sittings. The re-argument in the Louisiana redistricting cases is probably the biggest headline across the two calendars—and will be on Wednesday, October 15.

Second, in addition to the tweaks to the Court’s docket-search functions that I noted last week, the Court has posted a fantastic new resource to its website—a digitized compilation of (most of) the records and briefs in every original jurisdiction case that was pending as of, or filed since, 1962. (Original jurisdiction cases are almost always disputes between two or more states, in which the Court functions largely as a trial court, rather than a final court of appeals.) I’ve written before about the volume of useful and/or interesting material that the Court’s staff continues to make more widely available to the public, but it’s awesome to see these efforts continuing.

Third, there was a surge in media discussion about the pending cert. petition by Kim Davis, and what it means for the future of the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling recognizing constitutional protection for same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges. (The surge seems to have been caused by the fact that the Court ordered the respondents to file a response to Davis’s cert. petition after they had waived their right to file such a brief. But such a move requires a request from only a single justice, and is in no way predictive of a grant of certiorari.)

As I noted on social media, although it is easy to be cynical about the Court these days, it seems to me that two things are true: For starters, I don’t actually think there are five votes, at least right now, to overrule Obergefell (even if my reasons are more about politics than law). But even if I’m wrong, there are all kinds of reasons why the petition in Davis is an especially poor vehicle for the Court to address that question—not least of which is the fact that Davis forfeited the question of whether Obergefell should be overruled by not raising it in the trial court. It’s understandable that the Court’s behavior has left so many folks skeptical of its fidelity to even a recent precedent like Obergefell. But even if Obergefell might be vulnerable at some point in the future, I would, quite frankly, be shocked if the Court granted certiorari here.

Fourth, and finally, I wanted to flag a letter ostensibly signed by Solicitor General Sauer that was filed in the Federal Circuit last Monday—in reference to the lawsuit challenging President Trump’s tariffs (in which that court heard oral argument on July 31). It’s not unusual for parties to file such a letter, known as a “28(j) letter” (because they’re authorized by Rule 28(j) of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure), to apprise courts of material new developments in a case after the briefing has completed. But Sauer’s letter is … astounding. Leaving aside that it’s not even on Justice Department letterhead; that Sauer’s electronic signature appears different from the one he normally uses (by including a “/s/” line); and that it cheats the word-limit for such letters (by taking out spaces in citations), the letter reads more like one of President Trump’s social media posts than a formal communication to a court by the Solicitor General of the United States.

Among other things, Sauer’s letter claims that, before President Trump’s tariffs, the United States “was a dead country,” and that, if the Federal Circuit rules against the tariffs and doesn’t immediately freeze its ruling, we could see “a 1929-style result,” in which “people would be forced from their homes, millions of jobs would be eliminated, hard-working Americans would lose their savings, and even Social Security and Medicare could be threatened.” I certainly wouldn’t put it past private lawyers to submit such a filing. But coming from an office that has earned a reputation over generations for its integrity and for the quality and candor of its formal representations not just to the Supreme Court but to the lower courts, as well, the letter strikes me as an alarming new low.

Turning to this week, we expect the second set of summer orders from the Court at 9:30 ET—all of which are likely to involve routine, housekeeping matters. By my count, there are still four significant emergency applications pending before the justices—two from the Trump administration (both of which I discussed in more detail last week), and two from Florida death-row inmate Kayle Bates, who is seeking to block his execution, currently scheduled for tomorrow (Tuesday) at 6 p.m. ET. The next ruling on an emergency application by the full Court will be its 123rd ruling on an emergency application this term—which will be a new record.

Finally, and further to the reasons why we launched this newsletter back in November 2022, I wanted to briefly note that I am going to start posting short videos with Supreme Court-related updates to TikTok (and, eventually, to Instagram). The videos will offer (very) brief summaries of the longer-form analyses provided here. But if you’re on TikTok, I hope you’ll check them out.

The One First “Long Read”:

Selectively Balancing the Equities

“Balancing the equities” is supposed to be the hallmark of preliminary relief in trial courts—and emergency relief in appellate courts. The issue arises at the outset of a case, long before it has worked its way through the court system. And the central question is which rule should prevail while the case proceeds: should courts block whatever the plaintiffs are challenging for the duration of the litigation, or should they allow it to continue (or go into effect)? Imagine that your neighbor is planning to start building on what you claim (but he disputes) is your property, and imagine that it’ll take some time to sort out who is correct on the law. Should you be able to stop him before a court has ruled that it is, in fact, your property—or only after? Might the answer depend upon exactly what he’s planning to build and how easily it could be undone?

Traditionally, that analysis is supposed to turn on a series of considerations. Part of the analysis necessarily centers on the plaintiffs’ “likelihood of success on the merits.” It would make no sense to temporarily block a state law or federal policy, for instance, if the plaintiffs have virtually no chance of succeeding in their efforts to challenge it. But likelihood of success is just one consideration; courts are also supposed to “balance the equities.” That’s shorthand for a (necessarily imperfect) assessment of which of the two outcomes will cause more “irreparable” harm—that is, harm that would not be undone even if that side ultimately prevails in the case. Thus, someone very likely to win would need to show that the harms weigh in their favor only somewhat; someone less likely to win would have to make a fairly overwhelming case as to the harms of not giving them interim relief.

For as long as I’ve been writing about how the Supreme Court handles emergency applications, I’ve suggested that one of the real defects in the current Court’s approach is in how it is (or, really, isn’t) balancing the equities. In some cases, the Court has appeared to reconfigure its analysis of “irreparable harm” to reflect the (deeply contestable) proposition that governments are always irreparably harmed when their policies are blocked. In other cases, the Court has suggested that the equities are a wash so long as both sides can point to substantial irreparable harm—without considering whether one set of harms would clearly be greater.

But the Court has never actually held that it is abandoning the traditional balancing of the equities—even as it has granted emergency relief to the second Trump administration in a slew of cases in which any balancing of the equities sure ought to weigh in favor of keeping the administration’s policy on hold. Indeed, one of the most common objections that the Democratic appointees (especially Justice Jackson) have leveled against the majority’s behavior in Trump-related cases has been how much it has failed to account for the equities.

Against that backdrop, I was rather surprised by the NetChoice ruling—not the result, but Justice Kavanaugh’s brief concurrence. In a nutshell, Kavanaugh’s basic argument is that, even though NetChoice is likely to prevail in its First Amendment challenge to Mississippi’s age-verification law,1 he voted to leave the Fifth Circuit’s (unexplained) stay intact because NetChoice hadn’t persuaded him that the balance of the equities supported keeping the law blocked. Kavanaugh provided no analysis for this proposition; he merely cited to a three-page passage in Mississippi’s opposition to NetChoice’s application.

There’s a lot to say about this (brief) opinion. For now, three points, in particular, seem particularly important.

First, Kavanaugh’s lone citation in support of his conclusion that the equities don’t favor NetChoice makes no sense. The cited pages (pp. 37–39) of Mississippi’s brief principally argue that the equities don’t favor NetChoice almost entirely because the district court (and NetChoice) were wrong about the merits. This sentence, for instance, leads the paragraph that takes up most of page 38: “On the equities, the district court and NetChoice both rely on their flawed merits assessments.” But Kavanaugh wrote that he is likely to agree with the district court and NetChoice on the merits.2 Citing to that passage of Mississippi’s opposition is thus almost entirely circular. (Indeed, only one court balanced the equities in this case in any detail—the district court, which held that they supported an injunction. If Kavanaugh disagrees, it sure would have been nice for him to provide a plausible explanation as to why.)3

Second, the need for that kind of explanation is especially applicable to Justice Kavanaugh—because of what he has said previously about when (and why) he believes emergency relief is appropriate, including in First Amendment cases.

For instance, more than any other justice, Kavanaugh has emphasized the importance of the likelihood of success on the merits in the context of emergency applications. His concurring opinion in CASA (the birthright citizenship case) is almost entirely devoted to the importance of the Court providing a uniform interim answer to whether governmental policies should or should not go into effect—discussion that, as I noted at the time, has vanishingly little to do with balancing the equities. Likewise, consider this passage from an April 2024 concurrence:

[N]ot infrequently—especially with important new laws—the harms and equities are very weighty on both sides. In those cases, this Court has little choice but to decide the emergency application by assessing likelihood of success on the merits. Courts historically have relied on likelihood of success as a factor because, if the harms and equities are sufficiently weighty on both sides, the best and fairest way to decide whether to temporarily enjoin a law pending the final decision is to evaluate which party is most likely to prevail in the end.

To be sure, that passage began with the observation that “If the moving party has not demonstrated irreparable harm, then this Court can avoid delving into the merits.” But Kavanaugh has also regularly endorsed the principle that even short-lived violations of the First Amendment necessarily produce irreparable harm—including the (unsigned) November 2020 majority opinion in Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo, in which the Court quoted Justice Brennan’s 1976 opinion for a three-justice plurality in Elrod v. Burns for the proposition that “The loss of First Amendment freedoms, for even minimal periods of time, unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury.” (Roman Catholic Diocese is not an outlier; Kavanaugh has alluded to the same conclusion in at least two of his own separate opinions respecting grants or denials of emergency relief.)

In other words, Kavanaugh’s statement in NetChoice is inconsistent with both his general approach to emergency applications (in which the merits tend to do most of the work) and his specific approach to balancing the equities in First Amendment cases (in which he has repeatedly written, or joined other opinions concluding, that any First Amendment violation causes irreparable harm).

Third, it has become a common tactic, among those who are less critical of the Court’s approach to emergency applications, to either wave their hands at charges of inconsistency or to try to come up with their own explanations for why the justices’ behavior may in fact be consistent (albeit with a principle un-articulated by the justices themselves). One of those explanations is that the justices have simply abandoned equities balancing when it comes to emergency applications—and are voting their (preliminary) views of the merits. Thus, the argument goes, Trump is winning all of his emergency applications because the Solicitor General is picking only those cases in which five or more justices are likely to agree with the federal government on the merits of its appeal (whether or not it agrees with the underlying legality of the challenged action).

But that’s why I found Kavanaugh’s NetChoice concurrence so revealing. It’s not just how thin it is in the abstract or how inconsistent it is with Kavanaugh’s own prior writings; it’s that it throws cold water on the principal argument that has been made in defense of the Court’s approach to emergency applications from the Trump administration—that the Court has simply given up on trying to balance the equities when deciding emergency applications. At least one of the key justices is now on record that he hasn’t—at least in some cases.4

That leaves one last defense against the charge of inconsistency: That the Court has abandoned traditional equities balancing in cases in which the federal government is a party (like the Trump-related cases), but not otherwise (like NetChoice). The problem here is two-fold: First, there is no persuasive explanation for why the federal government, to obtain emergency relief, does not need to make the same showing as other parties. The Supreme Court’s authority to issue such relief comes from statutes that make no distinction based upon which party is seeking the justices’ intervention. And even if we’re treating governmental parties differently from private parties, the notion that the federal government always suffers some kind of unique irreparable harm when its policies are blocked that isn’t suffered even by state governments can’t be squared with the most basic principles of constitutional federalism.

Second, even if one were to find that possibility intriguing in the abstract, it is belied by recent history. During the Biden administration, there were three different cases in which the federal government sought emergency relief from the Supreme Court, the Court refused,5 and the government nevertheless prevailed on plenary review—i.e., on the merits. (The three cases were Biden v. Texas, United States v. Texas, and Dep’t of Education v. Brown.) Indeed, two of those three merits-stage rulings in support of the executive branch were unanimous.

The bottom line, then, is that Justice Kavanaugh’s NetChoice opinion seems to lead to one of only two conclusions: either one of the Court’s median votes is being inconsistent in how he balances the equities when considering emergency applications, or he isn’t—and is instead being maddeningly (and indefensibly) hypocritical.

SCOTUS Trivia: A Docket-Numbering Mystery Solved(?)

This is going to be remarkably trivial, even by my standards. But bear with me.

For as long as the Supreme Court has provided a public mechanism for electronically searching its dockets, it has adopted what appeared to be a strange (and hitherto inexplicable) convention for “original jurisdiction” cases.

Appeals and cert. petitions get the traditional “yy-nnnn” format, where yy is the relevant term (so, cases filed now are 25-1 et seq.); applications are “yyAnnn” (25A1 et seq.); and motions are “yyMnnnn” (25M1 et seq.). But original cases are docketed as “No. nnn, Original,” which is … hard to search for. Instead, to find an original case on the Court’s electronic docket, the key has always been to follow the form “22Onnn,” no matter what year the case was first filed (you can try this out for yourself; typing “22O150” into the docket search box returns Arizona v. California, which was filed in 2019). The mystery was why “22” was always the leading number.

Well, the new webpage with filings and records in original cases that I noted above appears to have (unintentionally) provided the explanation for why all original cases show up in the Court’s online docket with the leading numeral “22”: It turns out that 22 is almost certainly a reference to the year 1922—which was the year in which the oldest original case still pending in 1962 (when the Court totally overhauled how it numbers original jurisdiction cases) was originally filed. So 22O1 returns the docket for No. 1, Original—Wisconsin v. Illinois, in which leave to file an original bill of complaint was sought on July 14 … 1922. (The most recently filed original case, Nebraska v. Colorado, is No. 161.)

I suspect that this supremely nerdy mystery was keeping precisely none of you up at night. But it appears to have been solved.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one:

This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday. Have a great week, all!

Of note, Mississippi’s law is a much broader restriction than the one the Court just upheld in Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton, in which Texas had required age verification before accessing websites with adult material. The Mississippi law requires age verification (and the sharing of private personal information) in order to access any social media network for any purpose—hence the even graver First Amendment problems.

Mississippi also included a lone paragraph about the harms that have (or have not accrued) while the statute has been in effect, but NetChoice’s reply (see especially pp. 14–15) is quite compelling on that score.

One possible explanation (but not defense) of Kavanaugh’s citation is that pages 37–39 is just the full page range for Part III of Mississippi’s brief—the only part purportedly devoted to the “equities.”

This is also why I’m a bit surprised that we didn’t hear from any of the Democratic appointees in this case—especially Justice Jackson. Although their votes don’t seem as inconsistent with their prior behavior as Kavanaugh’s, it seems like this would’ve been an easy opportunity to score some relatively cheap points for consistency.

In one of the three cases (the challenge to the student loan debt forgiveness program by private plaintiffs), the application was deferred, and ultimately dismissed as moot after the Court (unanimously) concluded that the private plaintiffs lacked standing, but blocked the program in a separate case. The deferral thus had the same effect as a denial.

The decisions of the SC seem to bear less and less relationship to proper jurisprudence - and the letter purportedly from the Solicitor General beggars belief! Thank you for your time and trouble in setting out all these problems in detail, it's really wonderful to have such thorough explanations.

Retired Chicago appellate lawyer here. In my circuit (the 7th), a Rule 28(j) letter must be limited to submission of the new decision, along with a brief non-argumentative description of the point to which it relates. By brief, I mean typically no more than a sentence. If a lawyer filed a 28(j) letter like the SG's here, the court of appeals would squash that lawyer like a bug.