Bonus 157: Why the Supreme Court Keeps Granting Stays to President Trump

The justices have granted at least some of the relief the Justice Department has sought in each of its last 10 applications. There are some obvious reasons why, but also some less obvious ones.

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter (and unscheduled issues) will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, I put much of Thursday’s bonus content behind a paywall as an added incentive for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and I hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit.

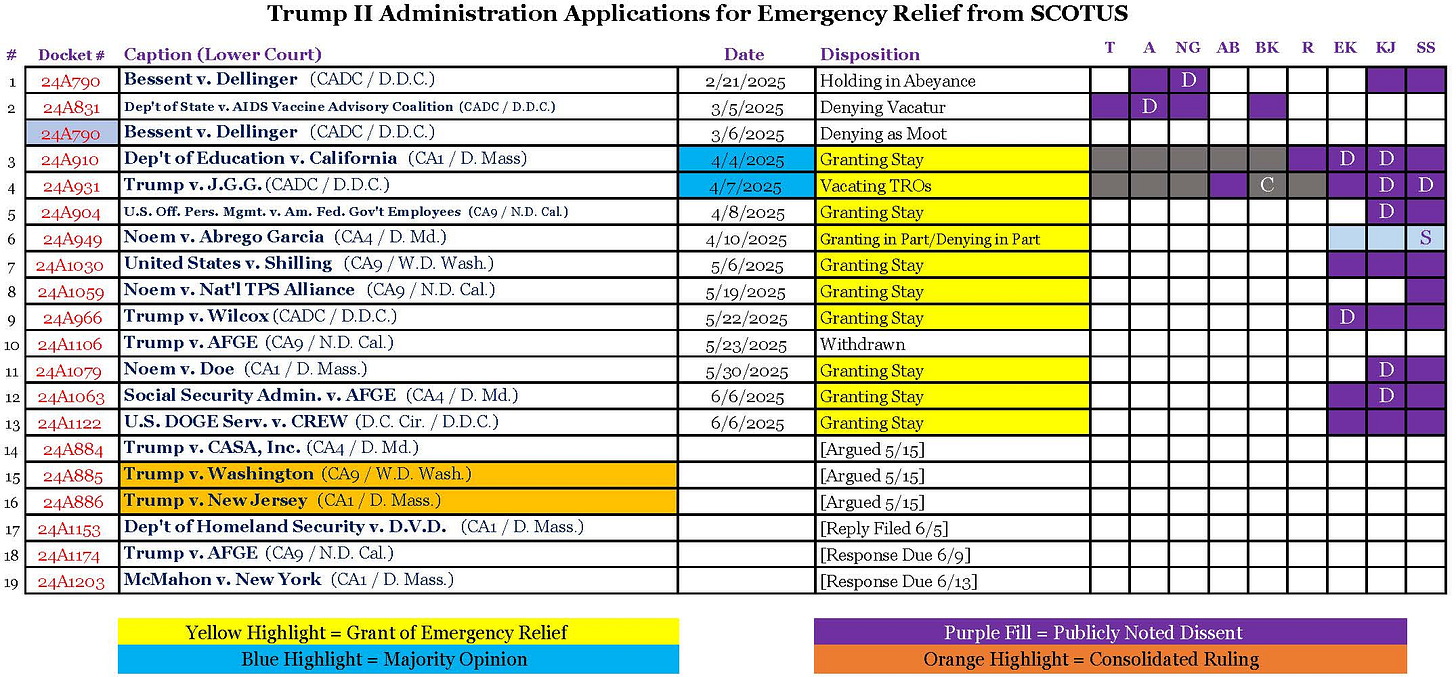

For this week’s bonus issue, I wanted to look more holistically at how the Supreme Court has handled emergency applications from the Trump administration—at least so far. As regular readers of the newsletter know, the federal government has filed an unprecedented number of requests for emergency relief from the Supreme Court—a total of 19 in the first 20 weeks of the second Trump administration. For comparison, the Biden administration filed a total of 19 applications across four years; and even that was a much higher total than, say, the George W. Bush and Obama administrations—which, across two two-term presidencies (so, 16 years), filed a combined total of eight(!).

What is becoming increasingly clear is that the Trump administration is not just seeking an unprecedented number of stays from the justices, but that it is doing very well in those cases. With the two rulings last Friday afternoon in the DOGE-related cases, the Court has now granted at least some relief to the Trump administration in 10 of the 12 applications on which it has ruled—and one of the other two applications (in the Hampton Dellinger case) was ultimately dismissed as moot. (See the chart below.) What’s more, at least one of the Democratic appointees has publicly dissented from nine of those 10 grants (the tenth was Abrego Garcia, in which the Court mostly ruled against Trump).

Why, if the Trump administration is faring so poorly in the lower courts, is it doing so well in these cases? The obvious answer, of course, is to focus on the current Court’s composition. Indeed, as the chart makes pretty clear, these cases are largely dividing the Court into its “usual” ideological camps. When that happens, one side has the votes, and one doesn’t.

But my own view is that that’s too simplistic an explanation. After all, plenty of Republican-appointed lower-court judges have ruled against President Trump, including in some of these very same cases. Instead, it seems to me that Trump’s success rate in the Supreme Court, at least to this point, reflects three different—but related—phenomena that are Supreme Court-specific: the effective abandonment, at least by a majority of the justices, of traditional equities-balancing when deciding emergency applications; careful culling of cases by the Department of Justice (which has not sought emergency relief from the justices in the substantial majority of cases in which lower courts have blocked Trump policies); and the volume of applications itself—which has ratcheted up the amount of capital the Court would have to spend to rule against Trump in more than a handful of these (and other) disputes, such as the Alien Enemies Act cases.

None of these explanations is meant to condone the Court’s behavior, of course. But understanding why the Court is doing what it’s been doing may be helpful not just to those of us who are watching (and trying to understand) the Court from afar, but to lower courts and those challenging the Trump administration’s policies in thinking about how best to mitigate the (steadily increasing) risk of emergency intervention from the Supreme Court.

For those who are not paid subscribers, we’ll be back on Monday (if not sooner) with our regular coverage of the Court. For those who are, please read on.

The Dataset

Let’s start with the dataset. I’m focused here only on applications filed by the Trump administration—and not on those in which the federal government is the respondent. I outline my reasons for focusing solely on “government-on-top” applications in the footnote at the end of this sentence.1 For now, that means I’m not counting the two times that the Supreme Court has granted emergency relief against the Trump administration—in the first and second rulings in “A.A.R.P. v. Trump,” i.e., the Alien Enemies Act case out of the Northern District of Texas. As of this morning, the Trump administration has filed a total of 19 applications. One was withdrawn (because it was mooted by proceedings in the lower courts). One was denied as moot (in Dellinger). And six are pending (including three in the birthright citizenship cases). That means there have been 11 up-or-down rulings to date. And in 10 of them, the Court has granted relief to the Trump administration, at least in part. (The only denial was the equivocal one in the USAID spending case.)

It’s worth stressing that two of the 10 “grants” were, on the big questions presented in those cases, losses for Trump. The grant of emergency relief in J.G.G., for instance, came in a decision that also required the Trump administration to provide to Alien Enemies Act detainees the very notice and opportunity to be heard that the Trump administration had tried to shirk. And the grant of emergency relief in Abrego Garcia only delayed the mandate that the government “facilitate” the return of a migrant wrongfully removed to El Salvador; it didn’t hold, as the Trump administration had asked, that federal courts couldn’t order such action in the first place.

Indeed, with one exception, the Court has gone out of its way to not express any positive opinion on the legal validity of the Trump administration’s actions in any of these cases. Some of the grants have been entirely unexplained; the others have been mostly on procedural—rather than substantive—grounds. But if anything, that only complicates efforts to explain the disconnect—between lower courts consistently ruling against Trump and the Supreme Court, at least in the cases before it, consistently putting those rulings on pause. Hence this post.

Why Trump Keeps Winning

Against that backdrop, my own view is that there at least three different reasons why the Trump administration’s success rate in these cases has been, at least to this point, so high—in contexts in which they have lost in the lower courts.

1. Abandoning the Equities

Analytically, the most significant explanation for this trend has to be the extent to which the justices have departed from traditional equities-balancing in considering emergency applications. Indeed, I’ve been arguing since at least 2019 that this is the principal feature that separates the current Court’s approach to emergency applications from that of its predecessors. And to whatever extent this shift was implicit in how the Court handled emergency applications during the first Trump administration, its rulings in the OSHA COVID-vaccination-or-testing case in January 2022 and Ohio v. EPA last term made it all-but explicit. What’s more, this has become the most common complaint in Justice Jackson’s opinions dissenting from grants of emergency relief—both in Trump-related cases and in others. If any of Justice Jackson’s critiques were not fair summaries of why her colleagues are voting the way they are in these cases, it would be easy enough for them to say so.

From my perspective, there are at least two different—but related—reasons why the justices’ effective abandonment of the equities helps to explain the Trump administration’s track record in these cases: First, the justices have mostly refused to acknowledge that this is happening. Indeed, as recently as last Friday, the Court invoked the traditional equities-balancing standard in its ruling in the DOGE-access-to-Social-Security-data case. That means that lower courts continue to be bound to apply traditional equities balancing in these cases even as the Supreme Court … seems to be doing something else. Thus, a court of appeals and the Supreme Court might analyze the same stay application from the government in ways that are materially different—and that may well tilt the analysis in the plaintiffs’ favor in the lower courts (given the massive disruptions caused by many of the Trump administration’s actions), but toward the government in the Supreme Court.

Second, if the justices aren’t engaged in a traditional balancing of the equities, then all that they are doing with emergency applications is guessing about how they’re going to rule on the merits—even in contexts in which the relevant factual and/or legal analyses may be woefully underdeveloped (if not wholly undeveloped) in the lower courts. Whereas a lower court might think that a close case on the merits nevertheless warrants preliminary relief because the equities tilt heavily in favor of the plaintiffs, the justices may think that, even it it’s 51/49 on the merits for the government (and “merits” can include “some procedural issue that should have foreclosed relief”), that’s all that matters. Again, I am on record as believing that, for a host of reasons, this is a major problem in how the Supreme Court approaches emergency applications. The relevant point for present purposes is that, feature or bug, it is increasingly undeniable that it is what the justices (or, at least, a majority of them) are doing. And if all that the Court is doing is previewing its views on the merits in contexts in which lower courts are told to decide something else, it is all the more understandable why President Trump would fare so well before this Court, in particular.

2. (Mostly) Picking the Right Fights

The second piece of this story is how well aware the Justice Department is of the Court’s abandonment of the equities in considering emergency applications—and how carefully it has sought to exploit that development by seeking emergency relief in only a small subset of the cases in which lower courts have blocked policies or conduct by the Trump administration. This is one of those points that seems obvious when you write it down, but is still worth stressing: Yes, the Trump administration has filed an unprecedented number of emergency applications in the Supreme Court, but the total is still a significant minority of the cases since January 20 in which lower courts have issued coercive relief against the federal government.

Within that self-selected subset, many of the federal government’s applications have centered on plausible (if not meritorious) procedural objections to the adverse district court ruling at issue—such as arguments that the plaintiffs lack standing; that their claims can’t be brought under the Administrative Procedure Act; that nationwide injunctions are categorically improper; that judicial review is foreclosed by statute; that discovery requests have been overbroad; etc. With the exception of the Wilcox case (about the constitutionality of for-cause removal restrictions on the firing of members of the NLRB and MSPB), virtually none of these applications have been litigated principally on the substantive merits of the challenged executive branch actions. Instead, in case after case, the government’s primary arguments for emergency relief have typically been tied to real or conjured procedural vulnerabilities in the relevant district court rulings.

Thus, instead of asking the justices to stay a district court injunction based on their determination that the conduct the injunction is blocking is actually legal, the government has shifted the focus to whether the district court injunction dots the right i’s and crosses the right t’s. If nothing else, that lowers the costs of granting emergency relief—because a justice could vote for emergency relief based on some procedural obstacle without having to believe that the government’s underlying conduct is lawful. And although we can’t be sure of exactly why the Court is granting emergency relief when it doesn’t provide an explanation, in the handful of cases in which the majority has explained itself, those explanations, with one exception (Wilcox, again), have invariably been procedural.

3. Spending (and Saving) the Court’s Capital

That distinction might be especially significant in light of the last piece of this puzzle—the very real possibility that at least some of the justices (especially the justices in the “middle” of the Court) are worried about how much capital they have to expend in confrontations with President Trump. Even during the Biden administration, when we didn’t have the same kind of loose ideological alignment between the executive branch and a majority of the Court, the justices still granted emergency relief to the federal government more often than it denied it (in 10 of the 19 cases). And that was when you didn’t have nearly as much noise coming out of the White House about impeaching federal judges; not having to comply with “unlawful” rulings; etc.

It’s interesting, in this respect, that President Trump didn’t fare quite as well with respect to emergency applications during his first term. Indeed, although the federal government sought emergency relief from the Supreme Court 41 times from January 20, 2017 through January 20, 2021, the justices granted at least some relief in 28 of those cases—meaning that, in roughly one-third of the requests, the Trump administration did not get the relief it was seeking. Perhaps it was easier for the Court to reject some of those applications in the very different political culture of the first term—when Trump still faced at least some constraints both from within the executive branch and from Congress.

Now, in contrast, it’s not hard to imagine a very real concern on at least some of the justices’ part that they have to keep their powder dry for the “big” cases—those presenting fundamental challenges to the role of the courts, if not the rule of law itself, such as the Alien Enemies Act and Abrego Garcia cases. Giving the Trump administration what it wants in cases in which the disputes are turning, or at least seem to turn, on more prosaic legal questions may thus be, whether consciously or not, an effort to reduce the frequency of direct confrontations between the Court and the President. Especially when the Court doesn’t have to actually validate the executive branch’s conduct to grant emergency relief (whether by not writing or by expressly relying on some non-substantive basis for relief), at least part of why Trump is doing so well may be at least somewhat connected to how often he’s asking—at a moment in which there has been a sustained and unprecedented attack from the executive branch with respect to whether federal courts should be pushing back against some (if not many) of these actions at all.

How Litigants (and Lower Courts) Should React

If the above analysis is even somewhat accurate, it lends itself to at least two different conclusions: First, there is every reason for the Trump administration to continue seeking emergency relief from the Supreme Court in at least some cases in which such relief has been denied below—especially where that relief is based at least in part on arguments unrelated to the underlying substantive validity of the government’s conduct. After all, not only is the government prevailing on most of these requests, but even as it has … taken liberties … in how it has presented some of these cases to the justices, it has suffered no consequences for doing so. There is thus very little downside to the government continuing to go to the well—even though it is already seeking emergency relief from the justices at an unprecedented (and, it would seem, unsustainable) pace. So long as the Court keeps granting a meaningful percentage of these applications—and says nothing to dissuade the government even when it denies them—there’s no reason for the government to change its behavior.

Second, from the perspective of lower courts (and those challenging Trump administration conduct going forward), this pattern also suggests that far more attention should be paid to the unspoken features of the Supreme Court’s approach to emergency applications. That doesn’t mean plaintiffs and lower courts should follow the Supreme Court in implicitly abandoning equities balancing or otherwise departing from the traditional standards for preliminary and/or emergency relief. But it does augur in favor of steering away arguments that are based primarily on the equities at the expense of the underlying likelihood of success in the lawsuit. Put another way, plaintiffs should be making arguments not just for why they’re entitled to preliminary relief, but why they really are likely to win on the merits—including in the face of plausible procedural objections. If there are potential questions about standing, the sooner plaintiffs can build the affirmative case, the better. Ditto if there are questions about the proper cause of action or about statutes that could be argued to foreclose judicial review. It may be unfair to require plaintiffs in emergency postures to try to not only make their entire case but anticipate and reject the government’s response, but it may also be increasingly necessary in the new normal the Supreme Court is creating and has created for these kinds of cases.

And lower-court judges should make sure that their analysis tracks these same understandings—that they are not just applying the appropriate test for their purposes, but also making clear to the Supreme Court why, in their view, a focus on the merits alone would lead to the same result. There are good reasons why, in the typical case, we don’t require litigants to anticipatorily reject the defendant’s counterarguments or the appellate court’s objections. But these are, alas, not the typical case.

Of course, no amount of comprehensiveness on the part of those challenging the Trump administration’s actions or lower-court judges reviewing them will necessarily prevent the Supreme Court from granting emergency relief. But it would at least make it harder for the federal government to accurately represent that those issues received short shrift from lower courts—and it would provide the justices with reasoned judicial analyses of issues that, in some of these cases, are being litigated almost entirely in the parties’ briefs. The more that this is how the highest-profile Trump policies are going to be litigated, the more it would behoove those involved in challenging those policies to internalize the extent to which traditional equities balancing is just not what the Supreme Court is doing anymore. We’d all be better off, in my view, if the justices weren’t so frequently (and, per Justice Jackson, selectively) departing from that standard. But so long as they are, proceeding in the lower courts as if things are normal is increasingly not going to be a recipe for success.

We’ll be back (no later than) Monday with our next regular issue of “One First.” Until then, thank you for your continued support of this newsletter—and I hope you and yours are staying safe out there.

The obvious problem with trying to capture all applications in which the federal government (or one of its officers) is a party is that there will be a lot of false positives in the dataset, because there are lots of applications in which a party seeks emergency relief against the federal government in a case that has nothing to do with Trump-related policies. (Consider, for example, Kapoor v. DeMarco, an application filed by a federal detainee seeking to block her extradition to India.) Rather than trying to make subjective assessments about which applications to count in which the federal government is “on the bottom,” it has always seemed easier to me, to simply focus on the applications the government itself chooses to file with the justices—and to try to distill patterns from that much more specific (and carefully cultivated) subset.

You say, “. . . many of the federal government’s applications have centered on plausible (if not meritorious) procedural objections to the adverse district court ruling at issue—such as arguments that the plaintiffs lack standing; that their claims can’t be brought under the Administrative Procedure Act; that nationwide injunctions are categorically improper; that judicial review is foreclosed by statute; that discovery requests have been overbroad; etc.”

And your (very generous) take on this is that the court may be saving its powder to deal substantively with a few more substantive issues. But you never consider the less generous take: That there is effectively collusion between the DOJ and the SCOTUS majority to effectively delay, delay, delay rulings on the merits or based on the merits because, with time, the Trump Administration can put such facts on the ground as to make it impractical to rule against the outcomes.

So, what about the argument that the SCOTUS majority is basically ‘ghosting’ us and that they are basically enabling the Administration to recast the Presidency and the rule of law around the goal of effecting the imperial presidency and a significant curtailment of rights and liberties Americans have won over the last century, and ‘the administrative state, including the regulatory guardrails that have brought principles and processes of democracy and equity into the marketplaces of commerce and ideas.

This explanation feels more likely to me than the one you’ve outlined. What say you?

I do have the sense that the majority is trying to preserve its authoritative capital for the big cases, an approach I think Republican senators have also adopted, e.g., in approving Trump’s awful nominations. From the outside, it seems clear that this is a bad strategy—standing on principle becomes harder rather than easier the more you put it off.