158. The Court's Unanimity is Greatly Exaggerated

It's time for the annual influx of superficial (or otherwise overstated) claims about the justices' lack of division. There are at least four different reasons why such accounts fail to persuade.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); and we’ll usually have a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

As we head into what may be the second-to-last week before the justices rise for their summer recess, the internet is rife with the standard, mid-June accounts of how the justices keep handing down decisions that aren’t sorting them into their ideological camps. Indeed, the six decisions the Court handed down in argued cases last Thursday featured a grand total of only two dissenting votes—both of which came from Justice Gorsuch.

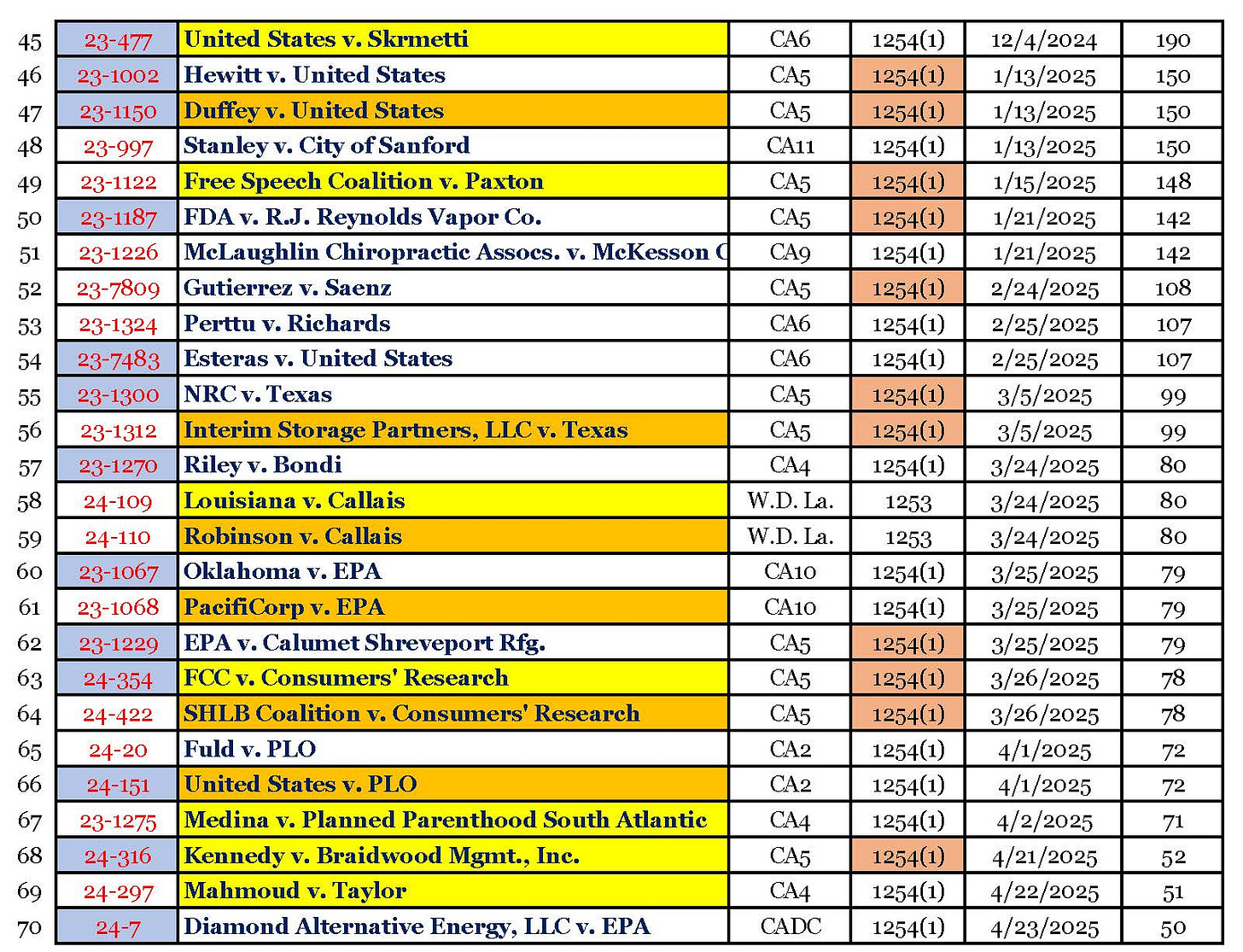

But as this week’s “Long Read” explains, there are at least four flaws common to virtually any narrative about the justices’ lack of division. First, it’s still way too early. By my count, we still expect at least 21 rulings from the Court in argued cases (20 from the “merits” docket, and at least one ruling on the three emergency applications in the birthright citizenship cases). And although that means that nearly two-thirds of the Court’s decisions in cases argued this term are behind us, it’s the most divisive cases that tend to get decided last. Here’s what’s left from this term:

Second, narratives about the justices’ alignment(s) continue to give indefensibly short shrift to the simple fact that these are (virtually all) cases that the justices have chosen to hear. Third, unanimity as to a judgment can often obscure far deeper (and ideological) divisions over the rationale. And fourth, these narratives tend to completely ignore the justices’ votes on emergency applications—where, as I explained last Thursday, the Court keeps dividing along ideological lines in the (unprecedented flood of) Trump-related cases. Sharp ideological divisions on emergency applications have been the norm for some time now. But the volume of such cases this term (and their importance) makes it indefensible to omit them.

More on all of this in a moment. But first, the news.

On the Docket

Because of the June 6 glitch, there was no regular Order List last Monday (the Court had released it the previous Friday). Instead, the Court handed down six miscellaneous orders over the course of the week—and then six opinions in argued cases on Thursday.1

All six of the full Court’s miscellaneous orders were denials of stays of execution, covering four capital cases—those of Florida prisoner Anthony Wainwright; Alabama prisoner Gregory Hunt; Oklahoma prisoner John Hanson; and South Carolina prisoner Stephen Stanko. No justice publicly dissented from any of the orders.

Of note, the last of the six orders (Friday’s order in Stanko) was the 100th order by the full Court respecting an emergency application during its current term. The only other term for which I have data (which is … most of them) that saw 100+ rulings by the full Court on emergency applications was last term—when the Court issued a total of 122. What is striking about this term is that the Court is already at the century mark even though there are 3.5 months to go until the term formally ends. The justices didn’t issue their 100th full Court ruling on an emergency application last term until August 28. It may not be remotely surprising that this term is almost certainly going to see a record number of full Court rulings on emergency applications. But it is certainly revealing.

Turning to Thursday’s decisions, I’m going to give them fairly short shrift, at least in part because they’re all pretty technical. Quickly:

In Rivers v. Guerrero, Justice Jackson wrote for a unanimous Court in siding with Texas (and the Fifth Circuit) about when new filings by prisoners in federal habeas petitions count as “second-or-successive” post-conviction claims (which are subject to far more limited review), rather than first claims.

In Commissioner v. Zuch, Justice Barrett wrote for an 8-1 majority in holding that the Tax Court loses jurisdiction to resolve disputes between a taxpayer and the IRS when the IRS is no longer pursuing a levy. Justice Gorsuch dissented.

In Martin v. United States, Justice Gorsuch wrote for a unanimous Court in reviving a lawsuit arising out of the FBI’s 2017 raid of the wrong house in suburban Atlanta. Although the facts of this case helped to generate headlines, the ruling is remarkably narrow—sending the case back to the lower courts to resolve whether there are other grounds under which the federal government may invoke its sovereign immunity to defeat the suit.

In Parrish v. United States, Justice Sotomayor wrote for a six-justice majority (Justices Thomas and Jackson concurred in the judgment) in a hyper-technical dispute over whether civil litigants in federal courts need to file a second notice of appeal if their first notice was filed too late, but they have a meritorious basis for re-opening that deadline. The eight justices who sided with the petitioner all agreed, albeit for different reasons, that no second notice of appeal is required in these highly unusual circumstances. Justice Gorsuch dissented.

In Soto v. United States, Justice Thomas wrote for a unanimous Court in siding with veterans in a technical, procedural dispute over how different federal statutes interact with each other to determine the length of the period during which veterans are entitled to retroactive combat-related pay.

And in A.J.T. v. Osseo Area Schools, Chief Justice Roberts wrote for a unanimous Court in holding that schoolchildren pursuing disability-related claims under the Americans With Disabilities Act or the Rehabilitation Act do not need to meet any heightened showing for relief—and reserved, for future cases, albeit while reserving what the correct standard for relief under those statutes is. This led to separate concurrences from Justices Thomas and Sotomayor (the latter of whom was joined by Justice Jackson), who, suffice it to say, would answer that question differently.

Turning to this week, we expect a regular Order List at 9:30 ET this morning, and the Court is scheduled to take the bench (and hand down additional decisions in argued cases) on Wednesday at 10 ET. We’re rapidly reaching the point at which the Court often adds a second (or even third) decision day to the weekly calendar, but there’s no indication yet whether we might also get decisions this Friday in addition to Wednesday (the Court will be closed Thursday for Juneteenth—so it’s Friday or nothing for a second day).

Beyond what’s scheduled, we also continue to await the Court’s resolution of at least three different Trump-related emergency applications—the application in the third-country removal case, and the two applications relating to reductions-in-force (RIFs) of federal employees. All three are fully briefed; and the third-country removal case has been fully briefed since June 5. The elapsed time strongly suggests that some number of justices are writing, although we won’t know who or what until the ruling comes down.

On the Docket: The Not-So-Unanimous Court

Thursday’s six rulings, and the six from the previous Thursday, have rekindled the annual tradition of commentators overstating the extent of the justices’ agreement. Indeed, the Court has handed down 41 rulings so far in argued cases—including three summary “DIGs” (dismissing certiorari as improvidently granted) and one summary affirmance by an equally divided Court. Even if we don’t count the one “per curiam” ruling with an actual opinion (TikTok),2 22 of the 36 signed decisions have been unanimous (including one that was 8-0). That’s, obviously, a significant majority (61.1%). Thus, if one simply looked at this data in the abstract, one might buy into efforts to portray the justices as less divided than their critics claim.

But looking at this data in the abstract misses four different—but equally material—points, all of which help to reinforce how, as is often the case with the Supreme Court, the story is a fair amount more complicated, even if the bottom line may not be.

1. It’s Still Early

Let’s start with the easiest flaw in accounts of the justices’ alignments to date: It’s still way too early. For a host of reasons, the Court tends to back-load many (if not most) of its most important and most divisive rulings—to the last few decision days of the term. Take the October 2023 Term, for example: The justices divided strictly along ideological lines (i.e., 6-3, with the three Democratic appointees in dissent) in 11 cases. Eight of those 11 rulings came on or after June 14, 2024; and seven came in the Court’s last 13 rulings in argued cases. Not only that, but many of the biggest rulings the Court handed down last term featured this lineup—from the Trump immunity decision to Loper Bright to Grants Pass. And that’s not counting other high-profile rulings that sharply divided the justices—such as the 5-4 decision in Ohio v. EPA (handed down on June 27); the 6-3 ruling in the January 6 obstruction decision (handed down on June 28); or the rulings that divided the Court ideologically in the other direction—with some combination of Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett joining the Democratic appointees in the majority.3

To be sure, this term doesn’t have quite the same volume of super-high-profile merits cases (the ones outlined in yellow above). And the next ruling in an argued case that divides the Court 6-3 will be the first of this term. But it’s a very good bet that we’re going to see some sharp divisions (and sharp rhetoric) before the justices rise for their summer recess—at which point narratives about the Court’s alignment and agreement will almost certainly have to be … revisited.

2. Selection Bias

This will be a familiar point to long-time readers of this newsletter, but it continues to boggle my mind that narratives focused on the Supreme Court’s overall voting patterns don’t make more out of the fact that the justices are handpicking all of these cases. Indeed, we expect the Court to hand down only a single ruling this term in a case it had to hear (the consolidated cases arising out of challenges to Louisiana’s congressional redistricting), meaning that 98% of the Court’s rulings are coming in cases the justices decided to decide. Although we are not privy to the reasons why the justices agree to take up the cases they choose, we know enough to know that many of the grants are either to resolve divisions of authority below or to clarify important questions of federal law in contexts that have no (or, at least, no obvious) ideological valence. Just scroll back up to the capsule summaries of the six decisions the Court handed down last Thursday for evidence of this.

Again, I don’t mean to overstate things; this kind of selection bias has been a feature (or a bug) of the Court’s docket since at least 1988. And so it’s not a new point about this term in comparison to previous ones. But it has just never been the case that the Court devotes all or even most of its capital to ideologically charged disputes. Indeed, the October 2023 Term was perhaps the extreme outlier in that direction—and even it had 27 unanimous rulings (out of 59 signed decisions in argued cases).

3. Unanimous Judgments

Speaking of dead horses, those who count Supreme Court rulings by looking no further than whether any justice dissented are also missing what can often be enormously significant divisions over rationales. Indeed, media reports on decisions often conflate whether the judgment was unanimous (meaning all nine justices voted to affirm or reverse the lower court), and whether the opinion was unanimous. Consider, in this regard, the Court’s May 29 ruling in the Seven County Coalition case—an important dispute about the National Environmental Policy Act. Technically, that ruling will go in the books as unanimous; it was 8-0 (Justice Gorsuch was recused) to reverse the D.C. Circuit and remand the dispute. But in reality, the ruling was 5-3, with the three Democratic appointees concurring only in the judgment—and on far narrower grounds that would’ve taken much less of a bite out of a critically important environmental protection law than Justice Kavanaugh’s majority opinion.

Again, the difference between the vote count as to the result and the vote count as to the rationale is not a new phenomenon. It just seems to me that, when faced with especially high-profile examples of these kinds of disagreements, it is superficial, at best, to rely upon the former datapoint—without providing the context of the latter.

4. The Very-Not-Unanimous Emergency Docket

All three of the above points are not even remotely unique to the October 2024 Term. This last point may be. I’ve written before, in some detail, about how the Court seems to divide ideologically more often in resolving emergency applications than on the merits docket. And yet, while that’s been true for some time, it’s the quantity (and import) of the full Court’s rulings on emergency applications this term that really drives home the dangers of leaving this out of the narrative. I wrote just last Thursday about why President Trump has fared so well, thus far, in emergency applications brought by the Justice Department. But Thursday’s post also pointed out the Court’s ideological divisions in those cases—with at least one of the Democratic appointees dissenting from each of the last 10 rulings on government applications (all of which granted relief at least in part), and all three Democratic appointees dissenting from six of them (with Chief Justice Roberts joining them in one, and Justice Barrett joining them in another).

Given both how many of these rulings there have been (and will continue to be), and how important these rulings have been (and will continue to be), I don’t see any good argument for excluding them from narratives that purport to take a holistic look at how the justices are (or are not) getting along. Indeed, to whatever extent we might have treated the emergency docket as an afterthought during prior terms, there’s just no question that it is central to this one. Not including what data we have from it is ignoring what has become the dominant source of major rulings for the current Supreme Court. And that data tells a very different story than one in which the justices are agreeing all the time, or are dividing along unusual lines when they don’t.

***

Again, we’ll know a lot more in the next 2-3 weeks. Even if the Court somehow finds common ground in most of the remaining merits cases, though (and I’m not exactly holding my breath), we’re still leaving out quite a lot about what’s actually transpiring if we’re not focusing on (1) the Court’s own role in choosing these cases; (2) the disagreements among the justices as to the rationales even in some of the cases in which they’re aligned as to the judgment; and (3) the five-alarm fire that is the emergency docket—which is busier in both quantitative and qualitative terms than we’ve ever seen before. The justices aren’t dividing over everything. But when push comes to shove, this remains a Court the dominant characteristic of which is two solid ideological blocs with periodic movement in the middle.

SCOTUS Trivia: Justices’ Relatives

I’m hoping to have more to say in the coming days on the ongoing developments with respect to the deployment of troops in Los Angeles, including the temporary restraining order issued by Judge Breyer and the very quick stay of the same issued by the Ninth Circuit. For now, though, I thought I’d use the rare appearance of Judge Charles Breyer in the newsletter to nerd-out about justices’ relatives—since Judge Breyer is the younger brother of (retired) Justice Stephen Breyer.

It turns out that my work has been done for me by Stephen McAllister, former Dean of the University of Kansas School of Law and U.S. Attorney for the District of Kansas (among lots of other impressive professional accomplishments). In a pair of articles in the Green Bag, McAllister has sought to document many of the “famous people” in the justices’ family trees (including the two justices from whom the actor Christopher Reeve was a descendant—one on his father’s side, and one on his mother’s).

With regard to justice-justice relations, folks probably know the closest one the best (that John Marshall Harlan II was John Marshal Harlan’s grandson).4 There’s also Justice Rufus Peckham, who the Senate confirmed to the Court less than two years after it had rejected the Supreme Court nomination of his brother, Wheeler (by the same President, Cleveland, but for a different seat). And there are the two Justices Lamar, who, it turns out, were themselves distant cousins.

But my two favorite obscure pieces of justice-relative trivia are (1) the uncle and nephew who sat on the Court at the same time; and (2) the Chief Justice who swore in his own cousin as President (twice). The first pair is Stephen Field and his sister Emilia’s son, David Brewer, who sat together from 1889–1897. The second pair, of course, is John Marshall and Thomas Jefferson. As McAllister notes, Marshall’s maternal grandmother and Jefferson’s mother were first cousins—so Marshall and Jefferson were second cousins, once removed. That may explain … a lot.

But also, Christopher Reeve?!?

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday.

Until then, please stay safe out there.

A seventh order—by Justice Alito dissolving an administrative stay he had issued in a dispute between two businesses—appears on the “Orders of the Court” page. But because it was issued by a single justice, it doesn’t count as a ruling by the full Court.

Unlike signed opinions, in which the Court publicly identifies how each justice voted, there is no tradition of doing so for unsigned (“per curiam”) opinions. It stands to reason that the TikTok ruling was unanimous; we just can’t say so for sure.

Indeed, we’ve seen a handful of these already this term. By my count, there have been four 5-4/5-3 rulings in which the three Democratic appointees were joined in the majority by two of Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett (and one going the other way, in which Justice Barrett joined the three Democratic appointees in dissent).

The greatest question I ever received from a student in class was “how was Justice Harlan able to stay on the Supreme Court for quite so long?”

"But in reality, the ruling was 5-3, with the three Democratic appointees concurring only in the judgment—and on far narrower grounds that would’ve taken much less of a bite out of a critically important environmental protection law than Justice Kavanaugh’s majority opinion."

This is the second time you have said something like this and it at least requires an argument and not an ipse dixit.

NEPA isn't a substantive environmental statute. It doesn't regulate a single pollutant or clean up a single site. It is a procedural statute that requires environmental impact statements and then allows lawyers for rich people to sue and block the project because some detail of the report was missing. It is a great statute for rich people and for environmental lawyers' paychecks but it doesn't protect the environment.

SCOTUS cut it back and therefore cut back on the ability of extremely wealthy people to file NIMBY suits to prevent the government from building stuff. Seems fine to me.

Thank you Steve .