188. Five Questions About "Extrajudicial Killings"

There is no obvious legal argument to support President Trump's expanding campaign of strikes against alleged drug boats in the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean. And the implications are even scarier.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court (and related topics) more accessible to lawyers and non-lawyers alike. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks:

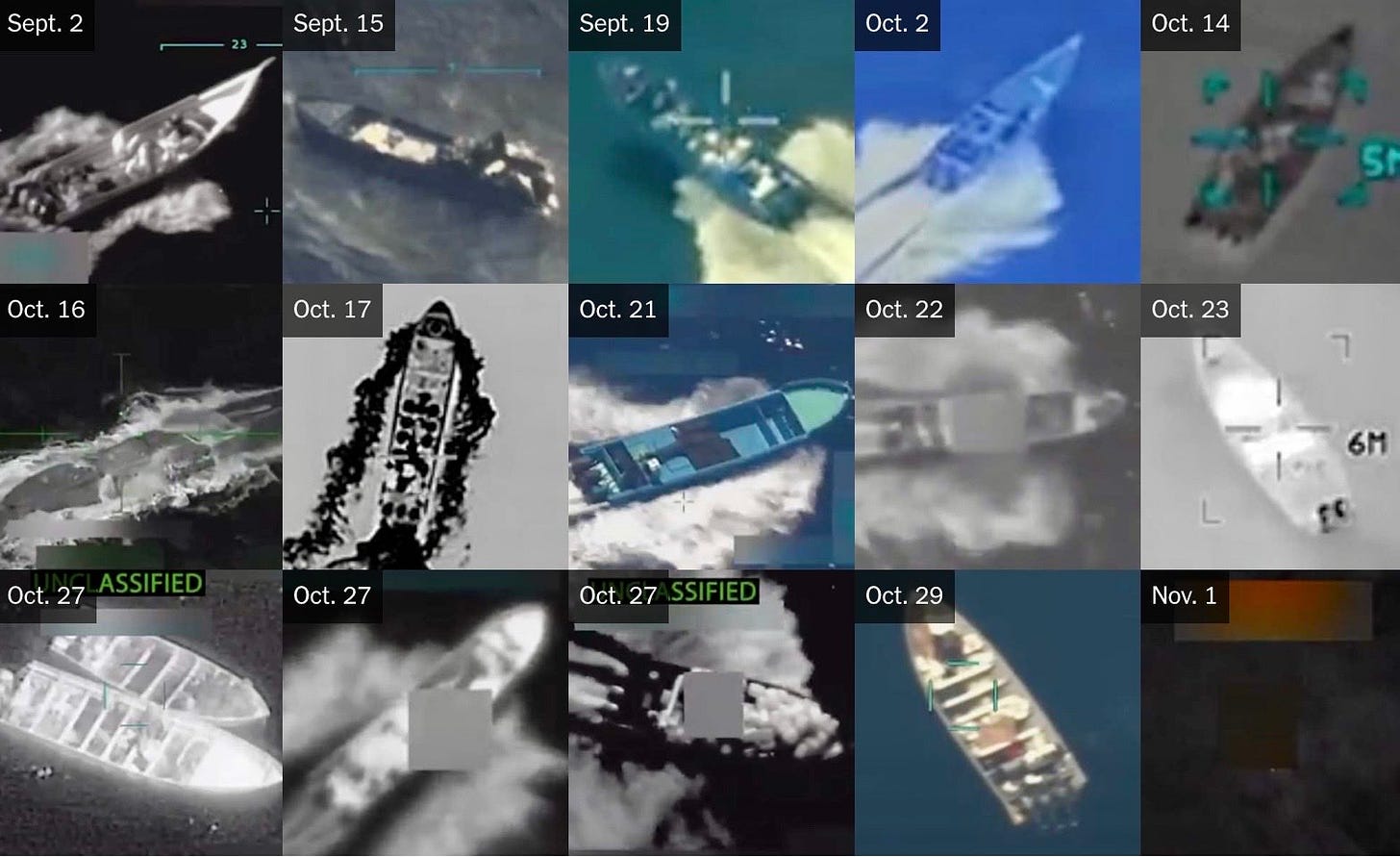

Thursdays are usually when I put out the weekly “bonus” issue of the newsletter. But given that I already put out a bonus issue on Tuesday (previewing yesterday’s arguments in the tariffs cases, which, IMHO, didn’t go very well for the Trump administration), I wanted to take this opportunity to address a critically important topic that I haven’t yet been able to cover: The Trump administration’s (ever-expanding) campaign of military strikes against alleged drug boats in both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean. According to the New York Times, which is closely tracking the strikes, there is now public confirmation of at least 16 strikes in those geographic areas that have killed at least 67 individuals (and from which at least two others survived).

There’s no question that, over the last half-century, we’ve seen a significant drift of war powers from Congress to the executive—one that many have long criticized, myself included. It is therefore possible that at least some folks have become desensitized to these headlines by the military force exercised by previous presidents—and view what’s happening in the Caribbean and the Pacific as different, if at all, only in degree. When we’re drinking from a firehose, it’s hard to focus on the individual spouts of water. But the post that follows explains why this is a serious underreaction—and why there is, especially as of this past Monday, no viable legal basis under U.S. law for what the Trump administration is doing.

Worse than that, whatever the internal legal rationale for these strikes is (and the Trump administration has pointedly refused to share it with anyone other than a handful of Republican members of Congress), there’s no publicly obvious reason why it would be limited to non-citizens and/or targets outside U.S. territory. Kentucky Senator Rand Paul was absolutely right to describe these strikes as “extrajudicial killings,” a term that has come to be used to refer to targeted uses of force by the state against specific individuals. But they’re even worse than that, for they are, near as I can tell, blatantly unlawful as a matter of U.S. domestic law—and a quickly spreading stain on whatever is left of the executive branch’s commitment to the rule of law.1

To help unpack these issues, the post that follows asks—and attempts to answer—five questions. If you prefer a more interactive version of what follows, I sat down with my friend Joyce Vance on Monday night for a Substack Live interview that’s archived here.

I. What is the Trump Administration Claiming?

The most official statement we’ve received from the Trump administration about the strikes is a notification President Trump sent on September 4 (ostensibly to comply with the War Powers Resolution of 1973, about which more below). That letter asserts that:

Extraordinarily violent drug trafficking cartels that the United States has designated as terrorist organizations have wrought devastating consequences on American communities for decades, causing the deaths of tens of thousands of United States citizens each year and threatening our national security and foreign policy interests both at home and abroad. These organizations have evolved into complex structures with the financial means and paramilitary capabilities needed to operate with impunity, engaging in violence and terrorism that threaten the United States and destabilize other nations in our own Hemisphere.

And, thus:

In the face of the inability or unwillingness of some states in the region to address the continuing threat to United States persons and interests emanating from their territories, we have now reached a critical point where we must meet this threat to our citizens and our most vital national interests with United States military force in self-defense. Accordingly, at my direction, on September 2, 2025, United States forces struck a vessel at a location beyond the territorial seas of any nation that was assessed to be affiliated with a designated terrorist organization and to be engaged in illicit drug trafficking activities.

There is, apparently, a memorandum or other formal analysis by the Office of Legal Counsel in the Department of Justice that has (maybe?) been shared with some (Republican) members of Congress, but that hasn’t been shared with other members or, needless to say, the public. Thus, the best we can do is try to infer what the government’s arguments might be. And … they’re not good.

II. Does Any Statute Authorize These Strikes?

Let’s start with the easiest of the legal issues here: There is no statute that can fairly be read to authorize these strikes. Let me break this out into four parts:

First, and quite obviously, Congress hasn’t declared war against … anyone (since 1942). And although the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force remains on the books, and authorizes the use of “necessary and appropriate force” against those nations or organizations that were responsible for the September 11 attacks, there is no claim, nor could there be one, that the drug cartels to which these boats are allegedly connected fall within the aegis of that statute (or, obviously, the 2002 Iraq AUMF—which somehow still hasn’t been repealed).

Second, to whatever extent one might argue that the War Powers Resolution of 1973 actually tolerates unilateral uses of military force so long as they are of limited duration and scope (and, to be clear, this is quite a controversial argument all its own—and not one I’ve ever found especially persuasive), that argument necessarily collapsed earlier this week—when the 60-day clock triggered by President Trump’s September 4 letter to Congress ran its course. In other words, even the most open-ended reading of the WPR would’ve cut off the President’s authority no later than Monday—the day before the most recent strike of which we’re aware. (For an excellent, longer version of this argument, see this Just Security post by Bec Ingber and Jessica Thibodeau.) The Justice Department is apparently of the view that the strikes never triggered the WPR in the first place. That’s highly contestable—but for present purposes, it only underscores how the WPR can’t be a source of authority for them.

Third, the President’s reference to “designated terrorist organizations” may be an attempt to rely upon the authorities Congress has provided with regard to “foreign terrorist organizations” (FTOs) so designated by the Secretary of State under 8 U.S.C. § 1189. (In an earlier post, I wrote about the Trump administration’s troubling effort to create a new category of “domestic terrorist organizations” paralleling FTOs.) But even if that’s the case, those authorities all involve civil and criminal sanctions and penalties for those organizations and those who associate with (or provide material support to) them. Indeed, the point of the FTO designation regime is to empower the State and Treasury Departments to use an array of tools to throttle support for those entities. Not even in the heyday of the Bush administration’s response to the September 11 attacks did anyone suggest that the FTO regime also authorized military force—and for good reason.

Finally, although there are a series of statutes authorizing U.S. Coast Guard and Navy vessels to undertake drug interdiction efforts on the high seas, most prominently the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act of 1986, those statutes, too, are focused on the use of ordinary law enforcement authorities—where the Coast Guard (and, in some cases, the Navy) are authorized to stop and arrest individuals under their auspices. It may well be that, once in the midst of an interdiction operation, those U.S. ships would have the legal authority to respond to force with force. But that quite obviously isn’t what’s happening here.

Simply put, without an AUMF, without the WPR, without the ability to rely upon the FTO designation regime, and with statutes like the MDLEA focused exclusively on law enforcement, there’s just no viable argument that Congress has provided the kind of authorization for these uses of force that the Constitution generally requires. If anything, as my Georgetown colleague Marty Lederman has pointed out, these strikes probably violate a series of federal statutes.

III. What About President Trump’s “Self-Defense” Claim?

Instead, my best guess is that the Trump administration’s real argument, as alluded to only elliptically in President Trump’s September 4 letter, is that the strikes are in “self defense,” which, if true, would trigger the limited constitutional power the Supreme Court has recognized for the President to respond to attacks against the United States with military force by dint of his unilateral authority under Article II. Indeed, I doubt anyone would dispute that, on the morning of December 7, 1941, President Roosevelt wouldn’t have needed statutory authorization to order the military to shoot down Japanese fighters and bombers over Hawaii.

There have also been arguments, for some time, that the President’s constitutional self-defense power may extend even to “preemptive” self defense (so, attacking the Japanese aircraft carriers while they were in international waters on December 6). Not surprisingly, that view is controversial enough in its own right. But it also is necessarily limited by plausible evidence that the United States is under an imminent threat of attack by those it is attacking in turn. Here, the strikes are against boats that, to all appearances, lack both the ability and the intent to even reach the United States (or U.S. targets overseas), let alone to attack them.

Even if the boats are actively transporting drugs across the Caribbean or eastern Pacific Ocean (and that is a big “if”), there is no universe in which Article II of the Constitution could fairly be read to authorize unilateral military action by the President—any more so than President Roosevelt could’ve attacked weapons shipments between Germany and its allies in 1940 on the ground that those weapons might one day be fired at the United States. Nor is there any prior example of a President invoking Article II with such a tenuous connection to any evident need for self defense. Put another way, if this is enough to trigger Article II, what wouldn’t be?

IV. How Is This Different From Cases Like Anwar al-Awlaki’s?

As I suggested above, I think part of why this has not been a bigger scandal is because of the degree to which many Americans have become desensitized to uses of military force outside our borders. Thus, one superficial reaction may be to analogize what President Trump is doing to the drone strikes that came into vogue late in the Bush administration and throughout the Obama administration. Indeed, one of the more well-known examples of those strikes deliberately targeted—and killed—an American, Anwar al-Awlaki. If those strikes were lawful, how are these different?

There are, it seems to me, at least three critical differences. First, those strikes were invariably carried out under the auspices of the 2001 AUMF—a statute that specifically authorized the President to use offensive military force against individuals he determined were part of the organizations responsible for the September 11 attacks, to wit, al Qaeda and the Taliban.

Second, in those cases, the federal government generated—and, at least to outward appearances, rigorously applied—meaningful criteria to determine whether the individuals they were targeting were, in fact, members of the relevant organizations. Indeed, we’re privy to quite a fair amount of the Obama administration’s internal legal reasoning—not just about who could be targeted and under what circumstances, but how the government was taking steps to ensure that the target was who they said it was. Contrast that with what (little) we know about the recent strikes by the Trump administration—including the, frankly, staggering reporting, via Democratic Rep. Sara Jacobs, that “Pentagon officials said they needed to prove only that the targeted people were connected to designated terrorist organizations, even if the connection is ‘as much as three hops away from a known member’ of a designated terrorist organization.” The difference between targeting a specific individual against whom force could lawfully be used and targeting unknown individuals who might be as much as three degrees of separation removed from a “known member” of a designated FTO is … large.

Third, it was not a coincidence that virtually all of those strikes were carried out in parts of the world in which there was virtually no effective governmental control—i.e., where arrest and detention were not viable alternatives to lethal military force (such as the disputed parts of Yemen and the area along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border). Not only is there no evidence that this is true with respect to the Caribbean and Pacific Ocean strikes, but we know that at least one of those strikes resulted in the capture of two of the boat’s occupants. And rather than subject those individuals to long-term military detention or to criminal prosecution in a U.S. civilian court (both of which would’ve provided those individuals with a chance to contest the Trump administration’s legal and factual arguments), the Trump administration quickly repatriated them. That’s not what you do when you believe you have a strong case on your legal authority. (Ecuador’s government later released one of the men for lack of evidence of wrongdoing. The other man, from Colombia, reportedly remains hospitalized.)

Don’t get me wrong: I was (and remain) plenty critical of targeted killings carried out as part of the military operations authorized by the AUMF. But there’s just no comparison when it comes to the legal arguments in the two cases. Reasonable folks may disagree about operations like the one that killed al-Awlaki; I just don’t see the argument for using missiles to blow up drug boats because there’s a chance someone on the boat is “three hops” from a known member of a drug cartel.

V. What’s the Remedy?

Long before January 20 (or September 2), there has been a serious gap in the ability of those against whom the United States directs military force to obtain any judicial redress in U.S. courts. Although the reasons vary, courts have relied upon a series of procedural doctrines to avoid reaching the merits—including in the case of Anwar al-Awlaki himself. I’ve long been unpersuaded by that body of case law, but I can’t deny that it’s out there.

One possibility, of course, is that courts faced with uses of military force in such novel contexts—where the legal authority is so patently dubious and where there’s no obvious connection to an armed conflict—might be more willing to find those procedural obstacles validly overcome and reach the merits, assuming that any of the families of the victims would actually want to even try that route. I’m not especially optimistic (for non-citizens killed outside the United States, it’s not even clear which rights such a suit would be trying to enforce). But that’s not a reason to not try it.

The more significant possibility is for Congress to stir from its slumber—as, at the very least, Senator Paul already has. I understand that it’s hard to believe this Congress will motivate to do anything—especially when it comes to reining in President Trump. But some of that may be a reflection of public opinion, which, for various reasons, seems less galvanized by what the Trump administration is doing in the Caribbean and the eastern Pacific than I would’ve expected. (As for what Congress could do, the immediate task would be oversight and accountability for what’s actually happening; the longer-term task is to provide for more robust judicial review, as I proposed with respect to targeted killings back in 2014.)

Indeed, at least to my mind, there’s very little daylight between the debates we had in the spring over whether migrants were entitled to due process before they could be removed from the United States and the debate over whether the President has the authority to just blow out of the sea any boat suspected of drug trafficking in the wrong parts of international waters. Those latter cases may seem less immediately relevant to us than disputes about our family members, friends, and neighbors. But it’s not at all clear why whatever arguments the Trump administration is relying on to justify these strikes internally wouldn’t apply with equal force to boats on Lake Michigan or in the Chesapeake Bay. Put another way, if there are no consequences for these strikes, where will this administration stop?

Looking back at our history, we’ll never agree on the specific moment when presidential claims to war power crossed whatever line the Founders intended. But the one point that seems undeniable is that such a moment is necessarily in our rearview mirror. And if this President doesn’t have to justify what’s happening right now in the Caribbean and the Pacific, it’s terrifying to think of what other uses of force he and his successors wouldn’t have to justify next—in contexts far closer, both literally and metaphorically, to home.

Extrajudicial killings should be reserved for extraordinary cases in which we are as sure as we can be that the target is who we think it is; where the law authorizes the use of force against them; and where there’s no other means of incapacitating them. Whatever else is happening in these strikes, it sure ain’t any of that.

If you enjoyed this issue of “One First,” I hope you’ll consider subscribing—or, if you already do, upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

And regardless, we’ll be back (no later than) Monday with our continuing coverage of the Supreme Court—and the increasingly fraught legal questions around it.

Happy Thursday, all.

In this post, at least, I’m not going to delve into the questions these strikes raise under international law. Those questions are important in their own right, but my focus here is on the U.S. law side of the analysis.

Excellent and to the heart of the matter with,

“Kentucky Senator Rand Paul was absolutely right to describe these strikes as “extrajudicial killings,” a term that has come to be used to refer to targeted uses of force by the state against specific individuals. But they’re even worse than that, for they are, near as I can tell, blatantly unlawful as a matter of U.S. domestic law—and a quickly spreading stain on whatever is left of the executive branch’s commitment to the rule of law.1”

Bringing back the failed "War on Drugs" with even worse reasoning and potentially more devastating consequences. MAGA, indeed.