172. "Federalizing" D.C.

Like any federal enclave, the federal government has plenary power over the District of Columbia. But Congress has delegated most of that power to local officials; it would take new laws to undo that.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current issues, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

After a relatively quiet week at the Supreme Court, I wanted to use today’s post for a bit of a deeper dive on a topic that is (literally) Supreme Court-adjacent: President Trump’s threat to “federalize” the District of Columbia. As a long-time D.C. resident,1 I am, quite obviously, biased. But it seems worth putting into context both the historical relationship between the federal government and the District of Columbia and the relevant current statutes. To make a long story short, the Constitution gives the federal government “plenary” authority over the “seat of government.” But just about everything else—including the fact that the District of Columbia is the “seat of government”—is up to Congress.

And although Congress has retained, both for itself and the President, more authority over D.C. than over any other federal enclave (including, as especially relevant today, with regard to the National Guard and the Metropolitan Police Department), the critical point for present purposes is that it was Congress that created and stood up a local government in 1973. Congress may have the constitutional power to return the city to true federal control, but the President can’t do it all by himself.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

The only formal rulings to come out of the Supreme Court last week were four orders denying stays of execution to Tennessee death-row inmate Byron Black. None came with public dissents. And although the Supreme Court didn’t make any public announcement about it, it appears to have tweaked the format of (and perhaps upgraded) the docket pages for individual cases. Perhaps the change is related to the late-June glitch, in which the Court accidentally sent out premature e-mail notifications of orders in cases that hadn’t been publicly released yet to everyone who had signed up to receive them. Perhaps not. But in ordinary summers, that would be what passes for news from the Supreme Court in early August.

This August, though, we’ve now got two major pending emergency applications from the Trump administration (the 21st and 22nd, if you’re scoring at home). The first, which has been pending since July 24 (and is ripe for a ruling), involves a lower-court ruling that blocked the termination of NIH grants the subjects of which the government purported to find politically objectionable. The second, which is not yet ripe but will be later this week, involves a district court temporary restraining order that purports to bar ICE officers from conducting suspicion-less arrests as part of “roving patrols” in and around Los Angeles, which a unanimous Ninth Circuit panel, after holding argument, refused to stay on August 1. That application was filed on Thursday; Justice Kagan has ordered the plaintiffs to respond by 5 p.m. (ET) tomorrow (August 12).

And it’s a good bet that we’ll get a 23rd emergency application from the Trump administration as early as today—after the D.C. Circuit on Saturday night lifted its temporary freeze of a district court ruling and required the government to restore public access to a statutorily mandated database that tracks the expenditure of congressionally appropriated funds. The unanimous ruling was accompanied by a strident separate opinion by Judge Karen LeCraft Henderson (a rather conservative George H.W. Bush appointee)—which is worth reading if you haven’t seen it yet. Given that the D.C. Circuit’s ruling requires restoration of public access by this Friday, it’s hard to imagine we won’t get at least some movement from the Court this week, perhaps including an administrative stay from Chief Justice Roberts.

Today also marks three weeks since NetChoice filed an important emergency application asking the Court to put back on hold a Mississippi law that requires parental verification for access to most social media websites by minors. The district court had blocked the law on First Amendment grounds; the Fifth Circuit, without explanation, had stayed that order pending appeal. Clearly, someone is writing something at the Court. But unless you’re a justice, your guess is as good as mine whether that augurs in favor of a grant or a denial.

In addition to those three (and probably four) emergency applications, we may also hear from the Court this week on an application from Florida death-row inmate Kayle Bates, who is seeking a stay of his execution, currently scheduled for next Tuesday. In whatever order they come, the Court is, by my count, just one order away from tying, and two orders away from breaking, its all-time single-term record for full Court rulings on emergency applications (122, set last term)—with eight weeks still to go in OT2024.

Otherwise, the next expected news from the Court is the second tranche of summer housekeeping orders—which is due next Monday at 9:30 ET.

The One First “Long Read”:

The President and the District

Later today, President Trump is apparently holding a press conference at which he is going to unveil his plan to “federalize” D.C. in response to completely inflated (if not entirely bogus) claims about violent crime in the nation’s capital (which, according to the MPD’s own data, is down 26% to this point in 2025—and at a 30-year low). As with so many other things involving Trump, it will be important to focus on the specific actions the government takes, and not just the rhetoric coming out of the White House. But it seemed worth it to provide folks with a bit of a primer on what little the Constitution has to say about the District of Columbia—and the far more important things that Congress has (and hasn’t) said.

I. A Brief History of D.C. Governance

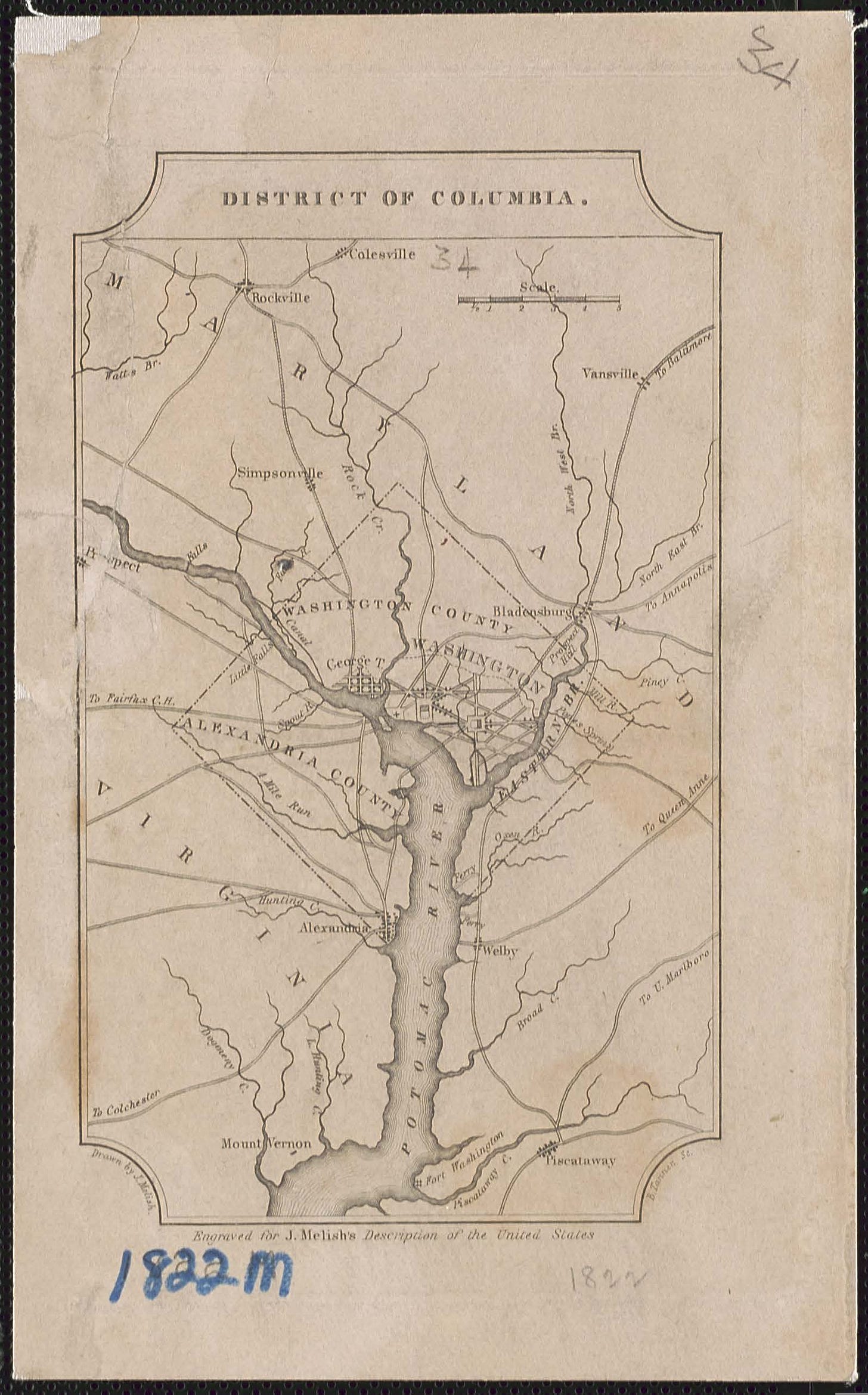

Let’s start at the beginning. The Constitution—even as amended—doesn’t mention the District of Columbia at all. It refers, instead, to “such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States,” over which Congress is given the power to “exercise exclusive legislation.”2 It was not the Constitution, but the Residence Act of 1790, that identified a general stretch of the Potomac River (between the Anacostia River and Conococheague Creek) as the spot for the seat of government—and that delegated to President Washington the power to appoint commissioners to identify the precise 10-square-mile plot that would become the “seat of government.”3 The “District” that the commissioners eventually identified (and that Washington and his Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, approved) included two existing settlements—Alexandria, Virginia and Georgetown, Maryland—and a new city to be built east of Georgetown, known for a time as the “Federal City,” but named “Washington City” by the commissioners in September 1791.

Under the terms of the Residence Act, the federal government formally relocated to Washington City in late 1800—which, at the time, was still governed by Maryland law. It wasn’t until the District of Columbia Organic Act, which was signed into law by President Adams on February 27, 1801, that Congress asserted full federal control over the entire District—which it divided into two counties, “Alexandria County” (the territory formerly belonging to Virginia); and “Washington County” (the territory formerly belonging to Maryland). Indeed, that was the bill that created positions for “justices of the peace” in both Alexandria and Washington Counties, to be appointed by the President, which helped to precipitate Marbury v. Madison.

And although Congress retained plenary control over the counties, it allowed Alexandria and Georgetown to continue exercising local authority; and it devolved upon “Washington City” comparable local governing authority in bills passed in 1802 and 1804. In essence, Congress served as the “state” government, but the three cities were allowed their own local control.

Except for the 1846 retrocession of Alexandria County to Virginia (because slavery),4 that’s how things largely remained until 1871—when the Civil War-era growth of both Georgetown and Washington City and a series of … problematic … inefficiencies led Congress to merge them into a single, local government. (1871 is thus when “Washington” and the “District of Columbia” became geographically indistinguishable, and when most dropped the “City” from “Washington City.”) Critically, Congress abolished that D.C.-wide local government in 1874—and took control of the capital itself—for complicated reasons, at least some of which was related to conflict between a Congress tiring of Reconstruction and the emerging political power of formerly enslaved people within Washington. (Indeed, slavery and its effects are lurking behind almost every corner in any attempt to recount the political history of the nation’s capital—going all the way back to the pitched battle over its location.)

For the next century, the District of Columbia was run by a three-member Board of Commissioners appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate (by law, one member had to be a Democrat; one a Republican; and one a civil engineer). Although the Board wielded both legislative and executive power, the true authority came from Congress—especially the powerful House and Senate Committees for the District of Columbia, which controlled appropriations and most of the relevant regulatory powers.

Finally, after decades of public pressure (in which the 1961 ratification of the Twenty-Third Amendment was but a step), Congress in 1973 passed the Home Rule Act—creating the District of Columbia government as we know it today. Among other things, the Home Rule Act includes the D.C. Charter, which creates legislative, executive, and judicial branches specific to the D.C. “local” government. And although Congress retained control of the judicial branch (yes, Congress, not the D.C. Council, controls the jurisdiction of the D.C. Superior Court and D.C. Court of Appeals, and the President nominates their judges),5 it gave substantial power and independence to both the Mayor of the District of Columbia and the D.C. Council—all of whom would be directly elected by the District’s voters, starting with Mayor Walter Washington in 1975.6

II. D.C. Governance Today

D.C. “local” law may be federal law for constitutional purposes (which is why the first major modern Second Amendment case came from D.C.—where the Second Amendment applied whether or not it also applied to states), but most of the real control of day-to-day life for Washingtonians belongs to the democratically accountable local government.7

Thus, the D.C. local government generally exercises plenary authority over local affairs in the District of Columbia, while the federal government retains authority over federal institutions in the District. So the U.S. Park Police can pull you over for speeding on the Rock Creek Parkway (or the Capitol Police for doing so in front of the Capitol), but ordinary crimes committed not on federal land are the purview of the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). So even “patrols” by federal law enforcement officers are mostly for show—again, unless they’re patrolling federal property or enforcing federal, as opposed to D.C. local, criminal laws.

Beyond the structural points noted above, there are three other ways in which D.C. is different even from the other five permanently inhabited federal territories—all of which have more control over their local affairs than D.C. does.

First, Congress retains the ability to “disapprove” of any legislation enacted by the D.C. Council through special, expedited procedures that aren’t subject to the filibuster. That’s a big deal for ordinary policymaking affecting Washingtonians; it’s actually the least important of the three exceptions for present purposes.

Second, although D.C. has its own National Guard, the Guard is commanded not by the Mayor (like Governors are the commanders-in-chief of state National Guard units), but by the President. (This is not because D.C. is a federal enclave; the other National Guard units in federal territories are commanded by the territorial governor; it’s a D.C.-specific historical quirk.) That means not only that the D.C. National Guard is always under the President’s direct control, but the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel has long taken the position that, unlike other National Guard units, the D.C. National Guard can therefore be used for federal missions without being federalized—which would mean they could be used for ordinary law enforcement purposes without violating the Posse Comitatus Act. This is a troubling loophole, but it is also a relatively a modest one; the D.C. National Guard is quite small—which is part of why President Trump relied upon out-of-state National Guard units in responding to the George Floyd-related protests in 2020. Thus, although the President using D.C. National Guard troops for law enforcement purposes in a context in which there is no plausible claim of emergency is troubling in any number of respects, it doesn’t come close to displacing the D.C. local government or more broadly “federalizing” D.C.

Third, and most significantly, the Home Rule Act gives the President the power to take control of the D.C. Police “whenever [he] determines that special conditions of an emergency nature exist which require the use of the Metropolitan Police force for federal purposes.” The authority is limited to no more than 30 days (it’s limited to 48 hours unless the President sends a special notification to the Chair and Ranking Members of the relevant congressional committees explaining why he needs the authority for longer). And even within those 30 days, the authority is simply to use the MPD “for federal purposes.” In other words, the President can borrow the MPD for his own priorities; but he can’t control how they discharge their other duties.

***

The upshot of all of this is that the President does have two important authorities when it comes to “local” law enforcement in the District of Columbia: He can use the (small) D.C. National Guard in circumstances in which he probably couldn’t use any other military personnel; and he can require the use of MPD “for federal purposes” for up to 30 days. That’s not nothing, but it also isn’t anything close to some kind of federal takeover of the nation’s capital. Unless there are other authorities out there to which no one has pointed, anything further would require new legislation—legislation that would be subject to cloture in the Senate (and, thus, would have virtually no chance of passing).

Of course, there’s still plenty to criticize about the federal government’s broader relationship with the District of Columbia—the 700,000+ residents (a larger population than Wyoming or Vermont) of which continue to pay their full share of federal taxes with no congressional representation. Indeed, it’s not just that D.C. lacks representation; it is that it is a common punching bag (or piggy bank) for members of Congress who have no need to worry about answering to the folks who live and work in the city in which Congress is located. But leaving the “this is why D.C. (and Puerto Rico) should be states” rant for another day, the relevant point for present purposes is that neither the Constitution nor any Act of Congress authorizes the President to “federalize” D.C. in general, even if, decidedly unlike what is true at this moment, there were a good reason for doing so.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Court and the District

Obviously, the Supreme Court sits in Washington. But you’ve probably never thought about the legal authority for that result. It turns out that section 1 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, the relevant language of which is codified today at 28 U.S.C. § 2, provided that the Court shall holds its terms “at the seat of government,” without further specifying where that seat would be. It was only the Residence Act, enacted just under 10 months later, that provided that Washington would be the “permanent seat of government” by December 1800—and that the seat of government would move first to Philadelphia by December 1790 and thence to the Potomac.

I wrote in detail in last Thursday’s bonus issue about the history of circuit riding, and the extent to which pre-1911 (and especially Antebellum) justices spent much of their time sitting on (often faraway) circuit courts. It’s interesting to consider, though, that Congress could also have the Court itself sit, at least every so often, in places other than the “seat of government.” Indeed, unlike Article I, which expressly refers to the “seat of government” in granting Congress plenary regulatory power over it, Article III is notably silent as to where the Court is to sit (and when).

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one:

This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday. Have a great week, all!

This is my second stint in D.C., and my third in the area. I lived in D.C. (in Shaw) from 2007–16 (while teaching at American); and in Silver Spring from 1993–98 (Go Blazers!).

Likewise, the Twenty-Third Amendment, which is often described as giving three electoral votes to D.C., in fact gives them to “The District constituting the seat of Government of the United States.”

Yes, Hamilton fans—this was part of the deal that Alexander Hamilton made with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison that’s memorialized in The Room Where It Happens.

By the mid-1840s, Congress was considering legislation to abolish the slave trade in the District of Columbia. Alexandria was a hub for the slave trade, and so its merchants and other local leaders lobbied both the Virginia legislature and Congress to accept retrocession before such a measure could be enacted (it was eventually adopted as part of the Compromise of 1850).

In an especially clever move, the Nixon administration pushed, as part of the Home Rule movement, to create “local” courts in the District of Columbia. (Prior to Home Rule, the D.C. district court and D.C. Circuit exercised both local and federal jurisdiction—which is a big part of why the old D.C. Circuit had such a dominant role in both administrative law cases and in Civil Rights Era criminal procedure cases.) By creating local D.C. courts, Congress would take much of the (then very liberal) D.C. Circuit’s jurisdiction away. And by leaving control of the new D.C. local courts with the federal government, the task of filling all of those new judgeships would fall to Nixon.

I’ll save for another time the unique role that the D.C. Judicial Nomination Commission is supposed to play in identifying nominees for the D.C. Superior Court and D.C. Court of Appeals—along with the debate over whether part of that role (appointing its own nominee if the President doesn’t nominate one of the individuals it recommends) might be unconstitutional.

One important exception involves prosecutors. Although the D.C. local government has an Attorney General, the D.C. Attorney General has no power to prosecute serious crimes—even those arising under D.C. local law. Instead, all prosecutions of serious crimes are handled by the U.S. Attorney’s Office—even for violations of D.C. local law triable only in D.C. local courts. D.C. is thus the only jurisdiction in the country that has no control over either any of the prosecutors who try its serious crimes or any of the judges who preside on its courts—let alone both.

Personally, observing everything Trump and his lackeys are doing in various other places like LA, it is clear he is setting the stage for further action of using federal law enforcement and the military to consolidate power. Both my husband and I, in our 70s, have always been independents (well-read, well-informed committed voters who have always tried to assess as best we can who would govern well and appoint quality people) and are not wild-eyed conspiracy mongers. However, having lived and worked in New York all of our careers and having observed Trump up close and personal for years, we had pretty much predicted everything that has happened in the last 10 years (and we don't think we are particularly prescient, just very clear-eyed about who the man is and who he would have around him this time around). So, we believe he is setting up conditions to not leave office, to remain physically ensconced in the White House even if he loses the election. And who knows what will happen in 2026? This regime is doing everything possible to rig elections going forward at the state level, But with DOJ's explicit backing. These activities to federalize DC are simply part and parcel and a first step of taking control of cities through federal law enforcement and the military. He's pushing the envelope and testing the waters, and certainly the Supreme Court isn't giving much pushback, at least where it really makes a difference. Do you think I am nuts?

Here are 100 protest signs. The moment demands protest. To each it should be unmistakable—urgent and morally unassailable. I speak for justice, duty, and shared humanity. Act now for those we must protect. Rise. We have protests to do. Good trouble. Restack these signs to spread your wealth.

https://hotbuttons.substack.com/p/100-free-protest-signs?r=3m1bs