161. The Court's Disastrous Ruling in the Third-Country Removal Case

The majority did not just greenlight an especially odious immigration policy without any explanation; it did so in a case in which the government defied the district court—twice—with no consequence.

Welcome back to “One First,” an (increasingly frequent) newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one (and, if you already are, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit):

I wanted to put out an extra issue this afternoon in response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in DHS v. D.V.D.—the unhelpfully captioned dispute over whether, before it can remove migrants to a country other than the one identified in their original removal proceedings, the federal government has to provide them with an opportunity to litigate whether they face torture or other forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment in that “third” country. (For more background, see my lengthy post on the case from May 30. The case is known as “D.V.D.” because those are the pseudonymous initials of the lead plaintiff.) Migrants are already entitled to challenge whether they face mistreatment in the country the government has designated for removal. The question here is whether they’re entitled to challenge the possibility of mistreatment in other countries the government identifies after the removal proceeding has concluded.

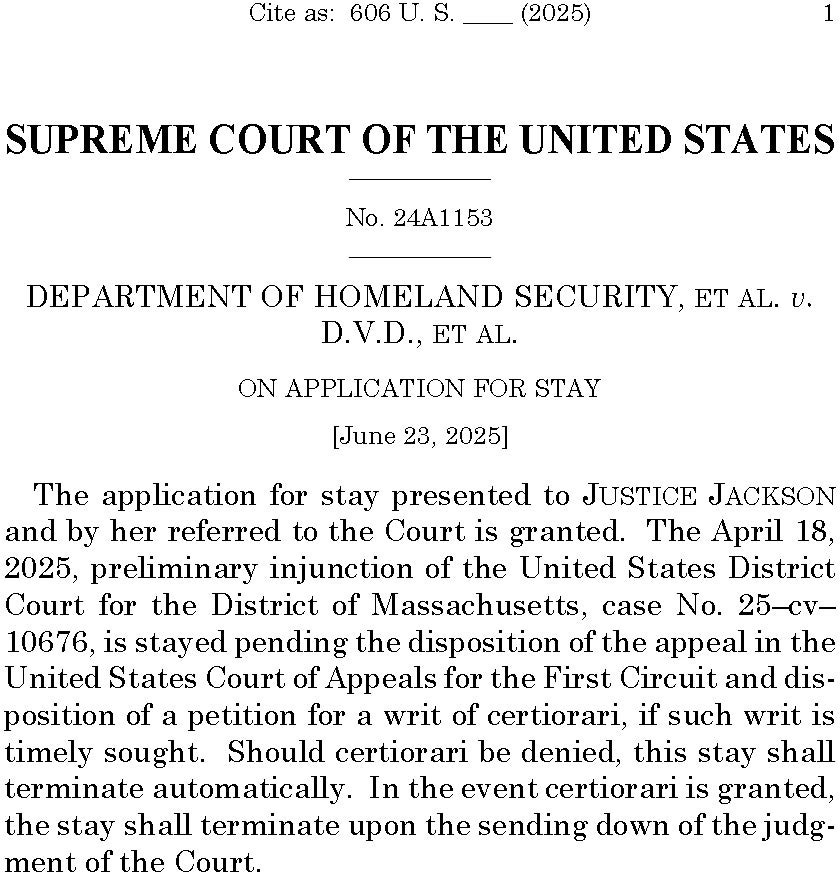

The district court had said yes—and had barred the government from removing individuals to third countries without at least some kind of process. But in an unsigned and completely unexplained order on Monday afternoon, the Supreme Court issued a “stay” of that ruling—allowing the government to immediately resume such removals without providing the process the district court required. Here is the sum-total of what the majority wrote:

Justice Sotomayor wrote a 19-page dissent, joined in full by Justices Kagan and Jackson. And she doesn’t pull her punches. Indeed, the dissent makes three distinct arguments, all of which should have militated against the relief the majority (again, with no analysis) provided.

First, Sotomayor reprises one of the arguments I made in my post from May 30—that equitable relief (like the stay the majority issued) is supposed to be available only to parties with “clean hands.” Here, the government’s behavior in the district court was anything but: “Here, in violation of an unambiguous TRO, the Government flew four noncitizens to Guantanamo Bay, and from there deported them to El Salvador. Then, in violation of the very preliminary injunction from which it now seeks relief, the Government removed six class members to South Sudan with less than 16 hours’ notice and no opportunity to be heard.” As Sotomayor explains, by not imposing any cost on the government for its misconduct, the majority not only defied a fundamental principle of equitable relief, but it is affirmatively threatening the rule of law itself. In her words, “This is not the first time the Court closes its eyes to noncompliance, nor, I fear, will it be the last. Yet each time this Court rewards noncompliance with discretionary relief, it further erodes respect for courts and for the rule of law.”

Second, unclean hands aside, Sotomayor explained in detail why the balance of the equities—which is supposed to be the predicate for any emergency relief—militates entirely against the relief the government sought. As she noted, “the plaintiffs in this case face extraordinary harms from even a temporary grant of relief to the Government.” Meanwhile, the government’s claimed harms (including having to temporarily hold a handful of migrants in Djibouti) were largely of their own making—thanks, again, to its defiance of Judge Murphy’s orders.

Third, even if all that matters is the “merits” (and, again, that’s not supposed to be true for emergency applications), Justice Sotomayor devoted six pages to rejecting all of the possible reasons why the government might prevail in this case—including why the district court properly had jurisdiction; and why removals to third countries without any opportunity to challenge the conditions the migrant could face there violates both the relevant immigration statutes and the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Of course, the government has counterarguments to these conclusions—some of which are at the very least plausible. But (1) my own view is that Sotomayor’s analysis of these issues is persuasive; and (2) in any event, the majority didn’t actually embrace any of those arguments. Instead, at least five1 of the same justices who, as recently as April, were especially adamant that alleged alien enemies have a right to notice and an opportunity to be heard before they can be removed under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 were willing to sign off on a ruling that effectively allows for countless other migrants to be removed to third countries where they have credible arguments that they’ll be mistreated—for no other reason than because they’ve already been held to be removable to some other country. Due process apparently matters to these justices on the initial removability question, but not beyond that.

***

As long-time readers of this newsletter know, I’m not prone to hyperbole. But the title of this piece refers to today’s ruling as “disastrous.” In my view, that’s a fair characterization for at least two reasons:

First, the ruling going to have massive (and potentially harmful) effects. Keep in mind that, in a pair of similarly unexplained grants of emergency relief to the Trump administration last month, the Court cleared the way for the government to treat as many as one million migrants as removable who weren’t previously (including those with “temporary protected status” and those covered by a humanitarian parole program started by the Biden administration). Those folks can now not only be placed in removal proceedings, but even if they can’t be removed to their countries of origin, they can apparently be removed to other countries without additional process—at least until and unless something changes. Some of these individuals may well have been convicted of crimes and/or are affiliated with gangs. But most haven’t been/aren’t.

Second, and even more importantly, here is one of the most stark examples to date of the Trump administration overtly defying rulings by a federal district judge. Indeed, it did so twice in this case. For the Court to not only grant emergency relief in this case, but to offer nary a word of explanation either in criticism of the government’s behavior, or in defense of why it granted relief notwithstanding that behavior, is to invite—if not affirmatively enable—comparable defiance of future district court orders by the government. I would’ve thought that this was a message that this Supreme Court would be ill-inclined to send, even (if not especially) implicitly. But it’s impossible to imagine that the Trump administration will view it any other way.

It’s a technical immigration case, to be sure. And it’s an unsigned, unexplained order. But today’s ruling is a massively important one for the Court and the country—and a massively worrying one, in my view, insofar as it at least appears to reflect the willingness of a majority of the justices to appease a government the behavior of which is increasingly unworthy of any such respect.

It’s possible that one of the six Republican appointees privately dissented, so we can’t say for sure whether the ruling was 6-3 or 5-4.

Retired 42-year lawyer here. Perhaps Prof. Vladeck can offer an explanation (to the extent there is one) WHY the Supreme Court is deciding these stay questions the way it is. For at least the last decade, maybe longer, I have fought the battle of the dinner table with my spouse over whether the Court is largely, maybe even purely, a political animal. I have maintained steadfastly that it isn't, that our legal system has at least a modicum of integrity. But I'm getting to the point where, barring some other explanation, I'll have to concede defeat.

Due process is gone