Bonus 193: The Pernicious Effects of Purcell

The remarkable row between the majority and dissent in the three-judge district court's ruling in the Texas redistricting case can be traced directly to the Supreme Court's election-related case law.

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter and other unscheduled issues will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, I put much of the weekly bonus issue behind a paywall as an added incentive for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and I hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit:

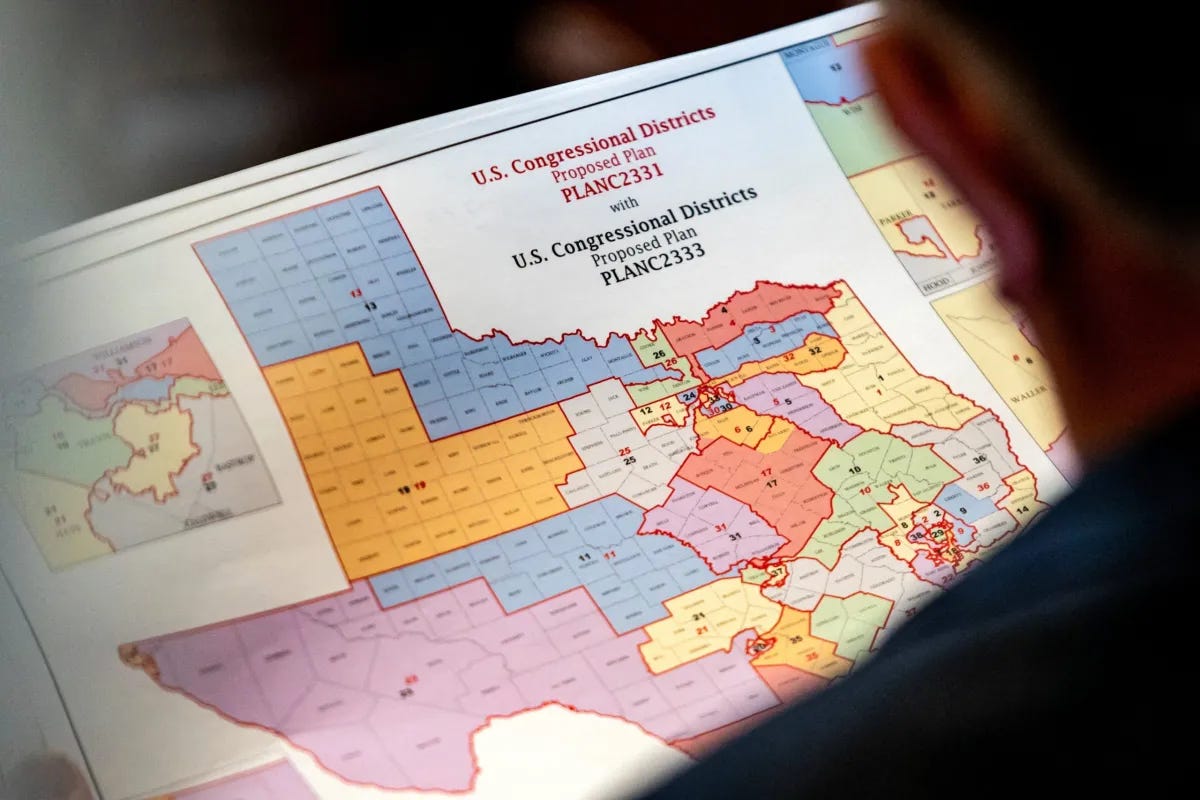

By now, you’ve likely seen at least some media reports about Tuesday’s ruling by a three-judge district court in the Western District of Texas,1 which blocked the Texas legislature’s attempted re-gerrymandering of its House districts in advance of the 2026 midterms. You may also have seen reports of the stunningly intemperate dissent that Judge Jerry Smith filed from that ruling yesterday afternoon. Indeed, even though the majority opinion was written by Judge Jeff Brown, a solidly conservative Trump-appointed district judge, and even though Judge Smith’s dissent reads more like an unhinged rant than a principled series of legal objections (it includes 17 different references to George Soros—who is … not a party to the case), the real point of contention is the majority’s decision to file its opinion without even waiting for the dissent—something it unquestionably had the raw power to do, but that reflects a clear breach of both protocol and ordinary norms of collegiality.

I don’t doubt for a moment that folks’ reactions to the majority and dissenting opinions in these cases are being—and will be—colored by their partisan political preferences. But without getting into who’s right and who’s wrong on the law (i.e., whether the Texas legislature engaged in unconstitutional racial gerrymandering), or what the Supreme Court will do when, not if, Texas seeks a stay of the district court’s ruling so that it can use the new maps next year, I wanted to use today’s bonus post to reflect on the Supreme Court’s own role in causing this mess. The real issue here is the “Purcell principle”—the idea that, to avoid confusion among voters and election administrators, federal courts should generally not change the rules governing elections as Election Day approaches, meaning that injunctions against even unlawful election rules are increasingly disfavored as Election Day draws near.

As I explain below the fold, one of the central problems with Purcell is the uncertainty the decision (and its subsequent applications) creates with respect to how far in advance of an election its “principle” applies. That uncertainty, in turn, creates perverse incentives—in both directions—when it comes to the timing of lower-court rulings sustaining legal objections to local or state election rules. Although the spat between Judge Brown and Judge Smith in the Texas case is an especially ugly one, the procedural disagreement animating it is, in many ways, the inevitable result of the Supreme Court repeatedly insisting that there is a point past which district courts can no longer intervene in elections, but refusing to be clear, in rulings that have spanned two decades, about exactly what (or when) that point is.

Purcell has other problems, too, but if nothing else, the drama arising out of the Texas case should drive home, yet again, why the Supreme Court ought not to be using its impoverished processes for resolving emergency applications (like Purcell) to embark upon fundamental shifts in the law.

For those who are not paid subscribers, we’ll be back (no later than) Monday with our continuing coverage of the Supreme Court. For those who are, please read on.