Bonus 136: Nationwide Injunctions vs. Nationwide Class Actions

If those who oppose non-plaintiff-specific relief are doing so on principle and not just politics, they should support more robust nationwide class action suits against the federal government.

Welcome back to the weekly bonus content for “One First.” Although Monday’s regular newsletter will remain free for as long as I’m able to do this, I put much of the bonus content behind a paywall as an added incentive for those who are willing and able to support the work that goes into putting this newsletter together every week. I’m grateful to those of you who are already paid subscribers, and I hope that those of you who aren’t will consider a paid subscription if and when your circumstances permit.

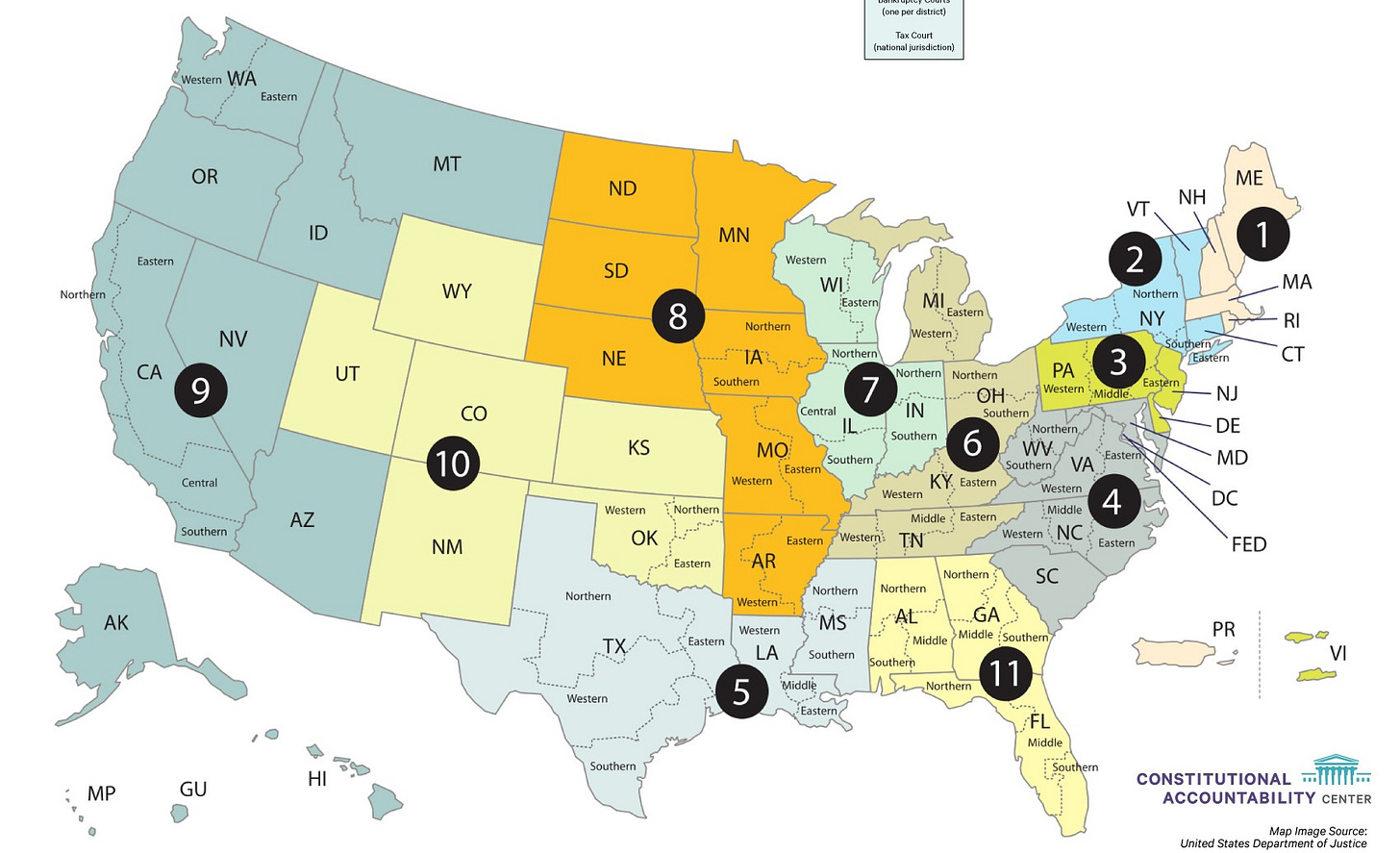

I wanted to use today’s bonus issue to reflect upon a pair of Supreme Court-related congressional hearings from earlier this week: Tuesday’s hearing before the full House Judiciary Committee, and yesterday’s hearing before the full Senate Judiciary Committee, both of which were ostensibly about the need to limit “nationwide” injunctions in reaction to the rash of such rulings against Trump administration policies (the distribution of which was the focus of Monday’s newsletter). [A “nationwide” injunction is one that bars the defendant from taking the challenged action in general, and not just against the named plaintiffs.]

I was the minority witness at the latter hearing, and used my testimony to focus on three basic claims: (1) that this seems like a uniquely poor moment for Congress to be focused on limiting the ability of the federal courts to rein in executive branch lawlessness; (2) that abuses of nationwide injunctions in recent years have been less about the scope of the relief district courts have provided than they have been about abuses by parties and courts of other procedural doctrines (especially standing and venue); and that any reforms should therefore be based on a holistic assessment of how to maximize accountability in both directions—so that courts are properly checked, but so that they don’t lose their ability to meaningfully check the other branches along the way. As I suggested, if Republicans’ current outrage is really about neutral procedural rules, and not just an attempt to insulate much of President Trump’s behavior from judicial review, one solution is simple: have any reforms go into effect on January 20, 2029.

But there’s another point that came up briefly during the Senate hearing that I wanted to expand upon here: Our judicial system already has a procedure for ensuring that every affected party can benefit from a single court order blocking an unlawful federal policy: the nationwide class action. And as I suggested in my testimony, it doesn’t strike me as entirely coincidental that the rise in nationwide injunctions over the past decade came right on the heels of a series of Supreme Court decisions that made it much harder for courts to certify nationwide classes of plaintiffs.

Nationwide class actions, in other words, should be playing a much more central role in debates over nationwide injunctions. Their long existence underscores that it’s generally permissible for a “single district judge” to enter relief that effectively blocks a state or federal policy on a universal basis. And their (problematic) neutering by the Supreme Court underscores that those who believe courts should be able to hold the executive meaningfully accountable, but who don’t love nationwide injunctions, have an easy fix: Reinvigorate the nationwide (or, for state policies, statewide) class action—something Congress unquestionably has the power to do.

In short, an easy way for Republicans to show that their hostility to nationwide injunctions is really about principle, and not just short-term partisan political gain, would be if any bill limiting nationwide injunctions simultaneously made it easier for courts to certify nationwide classes—at least when the plaintiffs are challenging federal policies (ditto, certifying statewide classes for challenges to state policies). Otherwise, opposing nationwide injunctions while refusing to consider an obvious, well-settled, and less controversial alternative leaves at least the appearance that the effort to limit nationwide injunctions is little more than an attempt to insulate this President, at this moment, from most judicial review.

For those who are not paid subscribers, we’ll be back on Monday (if not sooner) with our regular coverage of the Court. For those who are, please read on.

The “class action” is a procedural vehicle through which a single plaintiff or a small group of plaintiffs bring suit on behalf of a “class” of similarly situated individuals such that, if they “win,” the relief benefits the entire “class.” So, for example, if every single Social Security beneficiary was potentially affected by a change to how the Social Security Administration distributes benefits, one or a handful of beneficiaries could sue “on behalf of” all of the “class members,” and a victory would benefit not just the named plaintiffs, but every member of the class. There’s a lot of nuance and complexity here, and the rules vary a bit from state to state. But the basic idea is well-settled, and there are a ton of examples of nationwide class actions historically—both against private parties and against the government, and for both backwards-looking monetary relief (like damages), and forward-looking prospective relief (like injunctions).

In the federal courts, at least, certification of a class under Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure requires the lead plaintiffs to make four showings:

“Numerosity,” i.e., that “the class is so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable”;

“Commonality,” i.e., that “there are questions of law or fact common to the class”;

“Typicality,” i.e., that “the claims or defenses of the representative parties are typical of the claims or defenses of the class”; and

“Adequacy of Representation,” i.e., that “the representative parties will fairly and adequately protect the interests of the class.”

The upshot of the class action is fairly obvious: The ability to sue on behalf of an entire class not only makes relief more likely to run to all of the affected parties (which is especially important when challenging government action), but it also creates incentives for plaintiffs to aggregate claims that might be too costly to litigate on a one-by-one, retail basis. The downsides are also obvious: Class actions tend to be much bigger, much more expensive, and much more intensive lawsuits to both bring and manage—and, especially from the perspective of private defendants, can create extreme settlement pressures even in cases in which the substantive claims are relatively weak, simply to avoid or mitigate all of those costs. Thus, at least since the modern class action was memorialized in the 1966 amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, such suits have been viewed as an imperfect but necessary compromise.

As you might imagine, there’s a ton of case law analyzing each of these four requirements. But to make a very long story short, certifying a class was already no easy lift even before 2011 (more on that date in a moment). Indeed, the Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 was primarily intended to make it easier for defendants to remove to federal courts state-law class actions that were filed in state courts because the certification requirements (and other procedural rules) were more stringent in federal court than in many state courts.

The 2011 inflection point was the Supreme Court’s decision in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes. In that case, a group of female Wal-Mart employees had sought to bring a nationwide class action on behalf of 1.5 million Wal-Mart employees nationwide—alleging a systemic pattern of sex discrimination through pay inequity; hiring and promotion decisions; hostile work environments; and so on. At the core of the lawsuit were claims that each of these individual violations were symptoms of a broader disease. The Supreme Court unanimously agreed that the plaintiffs couldn’t bring their lawsuit as what’s known as a 23(b)(2) class action—and so agreed that, at the very least, they had to proceed under Rule 23(b)(3).1 But in an opinion for a 5-4 majority, Justice Scalia held that the suit couldn’t proceed under that provision, either—because the claims failed to satisfy the “commonality” requirement noted above. In a nutshell, there were too many different alleged violations and too many different theories of why each alleged act was unlawful.

The Wal-Mart decision had an immediate and significant effect on class certification decisions. And it was followed, two years later, by another 5-4 decision (with Justice Scalia again writing for the conservative majority) in Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, this time holding that nationwide classes couldn’t be certified in a case in which individual class members’ damages would vary significantly based upon where in the country they lived (even if the underlying allegation of wrongful conduct was the same).

Between them, Wal-Mart and Comcast have made certification of nationwide classes a much more difficult proposition in the lower courts. And they’re not alone. As Washington & Lee professor Suzette Malveaux has explained (in one of the only pieces to look carefully at the relationship between nationwide class actions and nationwide injunctions), there are an array of other barriers that both the Supreme Court and lower courts have erected—all of which have made it much harder to certify nationwide plaintiff classes, even in suits challenging nationwide policies. And those developments came right at the beginning of the modern uptick in nationwide injunctions—in which federal district judges started issuing relief against the federal government that ran not just to the plaintiffs, but to anyone potentially affected by the challenged policy. If you’re a plaintiffs’ lawyer today and the options are a nationwide class action or a nationwide injunction, the answer is obvious: You seek a nationwide injunction, since it doesn’t carry the burdens of class certification or any of the other additional procedural requirements attendant to class-wide litigation.

For many critics of nationwide injunctions, this distinction underscores the critique: The nationwide injunction is a less procedurally robust, more easily obtained shortcut around class actions. But I think these critics have things entirely backwards: The nationwide injunction is popular today entirely because it has become so unduly burdensome to certify a nationwide class and obtain relief in a nationwide class action. Put another way, what we’re seeing is Newton’s third law in action: because courts have made it so difficult to certify a nationwide class even in lawsuits challenging federal government policies, the response has been to find another, less obvious way to achieve the same kind of relief.

This brings me back to yesterday’s hearing. The two majority witnesses and the Republican members of the Committee kept insisting that their hostility to nationwide injunctions has nothing to do with the fact that they’re currently being used to thwart the policies of a Republican President. (In fairness, Professor Bray has been ruthlessly consistent on this point, but he may be a class of one. And as Professor Malveaux has suggested, even he has perhaps overstated the availability of nationwide class actions as an alternative.)

It seems to me that there’s an easy and obvious way for folks to prove that their objections really are procedural: Congress can and should adopt legislation to make it easier to certify nationwide classes—especially in suits challenging federal policies (likewise for statewide classes and state policies). Indeed, without doing anything to the jurisprudence regarding class actions between private parties, it seems like Congress can and should specifically authorize at least class-wide non-monetary relief in cases like the birthright citizenship cases—in which the challenge is a facial one to a national policy, and in which there are individuals who will be directly affected by the policy all over the nation.

There’s no question that Congress has the power to do this; the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure have the force of law because of a federal statute (the Rules Enabling Act of 1934). And there’s no question that Congress can supersede those rules by statute. Even the harshest critics of nationwide injunctions concede that federal courts have the power to issue relief that benefits nationwide classes of plaintiffs, so the real obstacles here are political, not legal.

And that, to me, is the key point here: If opposition to nationwide injunctions had nothing to do with broader views about when and how the federal courts should be able to hold the executive branch accountable, eliminating them in exchange for more robust nationwide class actions should (and, in my view, would) be a no-brainer. And insofar as those opposed to nationwide injunctions would also be opposed to a reinvigorated nationwide class action, that illustrates, quite powerfully, that their real objection is not to the ability of a single federal district judge (or even a three-judge district court) to provide relief that benefits non-parties; it’s to the ability of federal courts to exercise this kind of power over the federal government in any circumstances.

That’s certainly a coherent objection. But it’s one that has far less grounding in any statutory or constitutional foundations. And it’s one that, especially at this moment in American history, seems profoundly myopic. I’ve written at some length about how Congress should rein in procedural abuses of (and by) the lower courts. But kneecapping the courts’ ability to hold the executive branch accountable is problematic enough in the abstract; it’s only that much more so when we have a Congress that won’t do it, either.

A 23(b)(2) class action, the Court held, can’t be used when the principal relief being sought is monetary.

Thank you so much for your thoughtful commentary on this and other issues. I joined yesterday during Schiff’s time and your comments that I saw after that were very well done, and highlighted the insane contrast with the crap that Cruz, Schmitt and Panuccio were shoveling. It was a sorry spectacle for our democracy, but illustrated that half of congress is still trying to govern responsibly.

Steve: As always, your analysis is exactly right on. I viewed myself as a contrarian on the whole nationwide injunction issue, but your point about nationwide class actions actually addresses my concern, and your approach to having it apply to suits against the government seeking equitable relief rather than monetary damages squarely addressed the problem. What had bothered me about the furor about nationwide injunctions was that if a court finds an action by the government to violate federal law or, even worse, be unconstitutional, without some form of nationwide coverage, you have a situation where the unconstitutionality applies only with respect to certain plaintiffs or a particular geographic location, but not the rest of the country. If government action is unconstitutional, that determination should not be limited to just one state, say Texas, but then for the rest of the country, the government action -- even though having been found to be unconstitutional -- remains in effect as being just fine. That outcome is absolutely nuts -- something is either unconstitutional everywhere or nowhere. Your analysis of nationwide class actions is the perfect solution and addresses this in exactly the right way.