64. Federal vs. State Immigration Enforcement Under Arizona v. United States

The Supreme Court may soon be asked to revisit Justice Kennedy's 2012 majority opinion reaffirming federal primacy over immigration. Doing so could have implications far beyond the U.S.-Mexico border.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

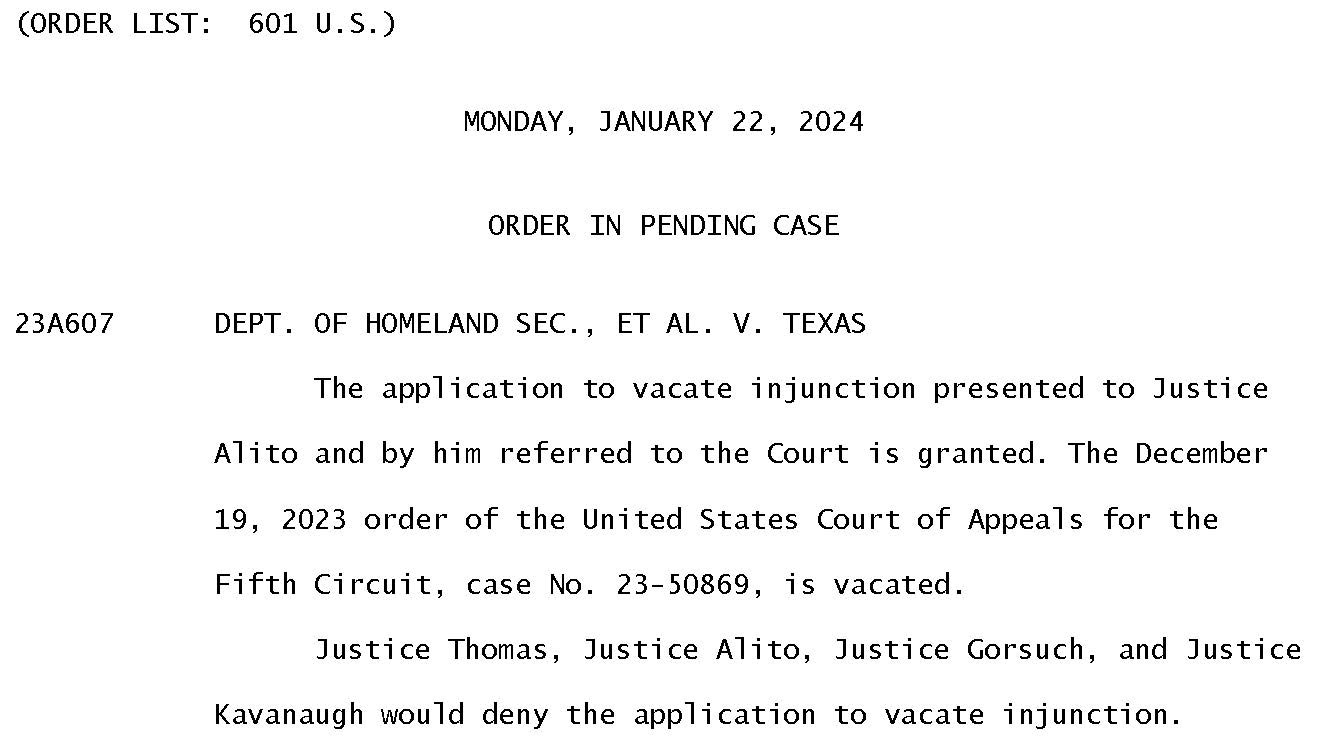

As predicted, the big news out of the Court last week involved a pair of emergency applications. First, on Monday, the justices handed down an unsigned, unexplained order in which a 5-4 majority granted the Biden administration’s request to vacate the Fifth Circuit’s injunction pending appeal in the dispute between Texas and the federal government over the latter’s removal of razor wire Texas placed along the U.S.-Mexico border (for background, see here). Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh dissented, but also didn’t provide any explanation. All we got was this:

Given how long it took the Court to … say nothing (the Biden administration had filed its application on January 2), one possibility is that there had been an attempt to say more, but there ultimately weren’t enough justices to form a majority. Regardless, perhaps the most important thing to say about the order is how little it actually resolved (someone really ought to write a book about why this is a bad thing): By vacating the Fifth Circuit’s injunction, the Court effectively protected the federal government from contempt sanctions if it continues to remove the razor wire that Texas has placed along the border—and nothing more. Thus, nothing Texas did or said later in the week was “defying” the Court’s ruling; much like President Jefferson and Marbury v. Madison, there was no real way Abbott could defy such a modest ruling because it wasn’t directed at Texas in the first place. Instead, as explained in more detail below, the real legal disputes between Texas and the federal government at the border remain very much open and unsettled (and are likely to only escalate further, given the politics of the moment).

It’s also worth noting that Monday’s order was yet another grant of emergency relief (1) to the Biden administration (the ninth in 14 tries); and (2) against the Fifth Circuit (the fourth this term and the eleventh(!) since the beginning of OT2021). As I’ve documented previously, the Biden administration has a surprisingly good track record in how its requests have fared, and much of that is because of how poorly the Fifth Circuit’s emergency interventions have stood up, both in cases involving the federal government and otherwise. I’m a broken record on this point, but the Court really ought to say something soon about the unnecessary mischief the Fifth Circuit keeps creating for it.

Then, on Thursday, the Court refused to step in to block Alabama’s second attempt to execute Kenneth Eugene Smith, even though he raised seemingly serious concerns about whether his execution by nitrogen gas (apparently the first ever) would inflict cruel and unusual punishment—concerns that some accounts from media witnesses of his subsequent execution appear to have borne out. Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson publicly dissented, with Sotomayor and Kagan each filing separate opinions (the latter of which Jackson joined). Even as the results in death penalty-related emergency applications have become completely predictable, the Democratic appointees appear to be picking the cases they find most disturbing to publicly object.

The Court also announced last week that it will next issue opinions in argued cases on Thursday, February 8—a move that will cause more than a little heartburn for the Supreme Court press corps, since that will be immediately followed by the oral argument in the Trump disqualification case. (No one other than arguing counsel is allowed to come and go from the courtroom, so those who want to be physically present for the Trump argument wouldn’t be able to cover any opinions until the argument is over.) And in an otherwise quiet Order List, the Court added an important death penalty case to their docket for next term—granting certiorari in Glossip v. Oklahoma, in which the state concedes that the defendant should get a new trial, but the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals still denied relief.

All of this activity obscures the fact that the justices are in the middle of their annual midwinter “recess”—so nothing is expected this week on either the orders or opinions front. That said, there’s a new emergency application from the plaintiffs in last year’s affirmative action cases, who are now challenging whether racial preferences at the federal military service academies are unconstitutional (Chief Justice Roberts specifically reserved that question in his majority opinion last June). Having not obtained relief yet from either the district court or the court of appeals, the plaintiffs are now seeking an emergency injunction pending appeal from the Supreme Court. Justice Sotomayor has called for a response by 5:00 ET tomorrow. I’ll just go out on a limb and say that I expect the Court to deny the application—albeit in a way that won’t necessarily tell us anything about how the justices would ultimately rule on the merits.

The One First “Long Read”: Federalism at the Border

There is a lot to say about both what is actually happening along the U.S.-Mexico border and the hyperbolic public rhetoric at both ends of the political spectrum surrounding the events in Eagle Pass. I already wrote a primer on the three cases currently underway; and I have a long post up at the Lawfare blog this morning on why Texas’s emerging constitutional argument—that Article I, § 10, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution allows it to impede federal enforcement efforts as part of its right to defend itself against an “invasion”—fails on multiple levels.

My goal in this post is to provide a bit of a broader overview of what the Supreme Court has said about the relative roles and responsibilities of state and federal governments when it comes to immigration policy (and federal law enforcement, more generally)—with an eye toward explaining (1) the difference between states supplementing federal authority and states supplanting it; (2) why sanctuary cities are different; and (3) why much of what Texas is currently doing is likely preempted by federal law, at least so long as the Supreme Court’s 2012 decision in Arizona v. United States remains good law. Of course, part of Texas’s strategy appears to reflect an organized and orchestrated effort to persuade the Court to revisit Arizona, but such a move by the justices would have potentially monumental effects far from the specific context of immigration policy.

Let’s start with four basic principles established by the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence:

Under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, conflicts between state and federal policy must be resolved in favor of the federal government, regardless of the relative strengths of the interests/arguments on both sides.

Although preemption of local/state law and policy comes from the Constitution, whether preemption has occurred is usually a question of federal statutory interpretation—to ascertain exactly what the federal policy is that is constitutionally entitled to preemptive effect. In other words, the constitutional principle is not in doubt; the real debate in these cases is over the scope of the federal government’s statutory authority.

The federal government cannot “commandeer” local or state law enforcement—meaning that neither Congress nor the executive branch can force local or state law enforcement to carry out federal laws.

Instead, local and state governments are free to choose whether or not to assist in the enforcement of federal laws—which is why sanctuary cities are generally not unconstitutional (and why they raise a different question from state or local officials impairing federal law enforcement).

Taking these principles together, the upside is that state and local governments are always allowed (but never required) to help federal law enforcement, but they are never allowed to usurp it.

It’s against that backdrop that the Supreme Court in 2012 decided Arizona v. United States. That case arose from “SB1070,” a controversial law Arizona enacted in response to claims that the Obama administration was not doing enough to enforce federal immigration law—and to empower Arizona officials to “assist” in those efforts. Among other things, SB1070 created several new state crimes related to being out of immigration status; barred undocumented immigrants from working or applying to work in Arizona; and created a host of new law enforcement authorities related to the enforcement of those prohibitions.

The federal government sued Arizona, arguing that most of SB1070 was preempted by federal statutes relating to immigration policy. And the Supreme Court mostly sided with the federal government. In an opinion by Justice Kennedy for a 5-3 majority (Justice Kagan recused, presumably because she had been Solicitor General at earlier points in the litigation), the Court concluded that three of SB1070’s central provisions had crossed the constitutional line.1 As Kennedy wrote, “[t]he federal power to determine immigration policy is well settled,” and “[f]ederal governance of immigration and alien status is extensive and complex.” Thus, the Court struck down the provisions that made it a crime for undocumented immigrants to fail to comply with federal registration requirements and to work or apply for work in the state, along with a separate provision that authorized state arrests for any conduct that made the non-citizen removable under federal law. In the Court’s words:

Federal law specifies limited circumstances in which state officers may perform the functions of an immigration officer. . . . By authorizing state officers to decide whether an alien should be detained for being removable, § 6 violates the principle that the removal process is entrusted to the discretion of the Federal Government. A decision on removability requires a determination whether it is appropriate to allow a foreign national to continue living in the United States. Decisions of this nature touch on foreign relations and must be made with one voice.

Thus, “[a]lthough [the Arizona law] attempts to achieve one of the same goals as federal law—the deterrence of unlawful employment—it involves a conflict in the method of enforcement” (emphasis mine).

This last point is key, for what Arizona drives home is that federal immigration policy is entitled to preemptive effect even when its critics believe that the laws on the books are not being adequately or appropriately enforced. Part of the President’s prerogative under the Take Care Clause is the right to set enforcement priorities—even when those priorities include non-enforcement in some cases in which that non-enforcement imposes costs on others. In the immigration context, specifically, it has long been true, politics aside, that the federal government lacks the resources to find, arrest, and remove every single non-citizen who is subject to removal from the country. Politics may drive which groups of removable non-citizens each successive administration chooses to prioritize; but limits on enforcement capacity is what requires prioritization in the first place.

Recognizing that reality (which Congress could address, but hasn’t), Arizona held that federal enforcement discretion is thus itself entitled to preemptive effect. Thus, states can’t adopt their own enforcement priorities—or try to impose them on the federal government. Justice Scalia’s acerbic dissent, on which Governor Abbott has relied in recent statements, only reinforces this reading of the majority opinion—even as he bitterly objected to it. As he put it, “[t]he laws under challenge here do not extend or revise federal immigration restrictions, but merely enforce those restrictions more effectively” (emphasis mine).

So framed, the question Arizona asks about what Texas is doing is not whether it is filling in gaps in the federal immigration enforcement scheme; it is whether it is making different policy choices about how to enforce immigration law than the federal government. And it’s pretty hard to look at the pending cases and conclude that the answer is anything other than “yes.”

Consider, in that regard, SB4—the new Texas immigration bill signed into law last year, and which is set to go into effect on March 5. The bill makes it a crime under Texas state law for noncitizens to enter or re-enter the United States without authorization (even though it is already a federal offense); allows Texas law enforcement authorities to stop, arrest, and jail those suspected of having committed the new state offense; and empowers state judges to issue de facto state-law deportation orders against those convicted of violating the new law.

The law further authorizes Texas law enforcement officers to transport noncitizens to a “port of entry,” at which point it is assumed federal authorities will take custody of the detainees and, perhaps, remove them from the country. If not, the bill creates a third crime for individuals who remain in the U.S. despite a state removal order. Finally, and perhaps most cynically, SB4 also purports to indemnify officials who, while enforcing the new state law, violate the federal Constitution or other federal laws.

Compared to the current disputes over buoys in the Rio Grande (which turns on the scope of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899) or razor wire along it (which turns on the scope of the federal government’s sovereign immunity), it is SB4 that truly represents the frontal assault on federal primacy in immigration. Indeed, what Texas is attempting goes even further than Arizona’s SB1070 in several critical respects—including the ersatz state deportation regime it purports to create. It would be difficult for an objective lawyer to compare SB4 to those parts of SB1070 that the Court blocked in Arizona and think that SB4 is less problematic from a preemption perspective; in key respects, it’s an even greater arrogation of the federal government’s immigration enforcement function—and discretion.

Instead, the real showdown Texas appears to be trying to provoke is not the one along the Rio Grande (which may be good politics, but is bad constitutional law), but whether the current Supreme Court is willing to stick by Arizona even as immigration has become even more of a partisan wedge issue (and as the Court’s center of gravity has shifted significantly to the right). Four of the justices who participated in Arizona remain—two from the majority (Roberts and Sotomayor); and two from the dissent (Thomas and Alito). It is not a wild prediction to assume that Justices Kagan and Jackson will hew to Justice Kennedy’s position and that Justice Gorsuch will align more with the Scalia dissent. That likely leaves the question to Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett, and it raises the very real possibility that last Monday’s cryptic, 5-4 vote in the razor-wire case (in which Justice Barrett joined the Chief Justice and the three Democratic appointees in the majority and Justice Kavanaugh joined Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch in dissent) could have been a harbinger of votes to come.

When (not if) the federal government’s challenge to SB4 makes it to the Court (a preliminary injunction hearing in the federal district court here in Austin is scheduled for February 13), the implications will be enormous—and not just for the future of immigration policy. In an era of congressional dysfunction in which presidents of both parties depend upon statutory interpretation to justify many of their most significant domestic policies, the question of whether those interpretations displace contrary state laws could arise with respect to everything from environmental regulation to consumer protection to drug control to public health to, well, you get the idea. And so as sympathetic as some of the justices (and outside observers) might be to what Texas claims it is trying to do along the U.S.-Mexico border, the real referendum is over whether all states, going forward, should be able to use disagreement with how federal policies are being enforced as a justification for carving out regulatory space to enforce policies all their own.

SCOTUS Trivia: Taney’s Capacity in Ex parte Merryman

The incorrect but loud public claims that Governor Abbott was “defying” the Supreme Court’s ruling last Monday (or, from the right, that he should defy it) bring to mind the most visible example of a President openly defying a ruling by a Supreme Court justice—President Lincoln’s refusal to comply with the writ of habeas corpus that Chief Justice Taney issued in Ex parte Merryman in May 1861. There is a lot to say about Merryman (and one of these weeks, when there’s a little … less news, I promise to go into a lot more detail on the truly remarkable dispute). But today’s trivia is much more trivial—about the specific capacity in which Taney issued the writ (and Lincoln defied him).

All agree that Taney acted by himself. (So Lincoln never defied the full Court.) What’s messy is that, under the relevant statutes, it is unclear whether Taney issued the writ in his capacity as justice of the Circuit Court for the District of Maryland (while “riding circuit” in Baltimore) or as a single justice of the Supreme Court “in chambers,” as section 14 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 authorized him to do. (He issued the writ from the federal courthouse in Baltimore, but the geography doesn’t control; “in-chambers” opinions can come from anywhere.) There is contemporaneous evidence (and there are plausible arguments) in both directions, along with academic arguments for why either was legally possible.

The good news is that there is literally no respect in which this distinction matters for present purposes—other than as the subject of a fun (and surprisingly intense) academic debate. At most, it might’ve affected how Lincoln appealed the ruling to the full Court if he had appealed it. Instead, Lincoln famously appealed to the court of public opinion—defending his actions in and around Baltimore in April 1861 both in legal and extra-legal terms in his July 4, 1861 message to Congress.

The better news is that, notwithstanding Andrew Jackson’s (“almost surely”) apocryphal quote about Chief Justice Marshall trying to enforce Worcester v. Georgia, we’ve never had an example of a President clearly and openly defying a decision of the Supreme Court. Much of that reflects just how profoundly politically damaging it would be for a President to do so. But it’s worth wondering (and worrying) about whether, as public confidence in the Court continues to erode, we might come to a point where the politics don’t cut so severely against defiance. As fantastical as such a scenario might have seemed as recently as a decade ago, consider the speed with which Republican elected officials called upon Governor Abbott last week to ignore this Supreme Court—and what it would mean for the Court and the country if he could have and did.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning. And we’ll be back with a regular issue next Monday.

Until then, happy Monday, everyone! I hope that you have a great week.

The Court reversed that part of a lower-court injunction that had blocked the SB1070 provision requiring state officers to make a “reasonable attempt . . . to determine the immigration status” of any person they stop, detain, or arrest on some other legitimate basis if “reasonable suspicion exists that the person is an alien and is unlawfully present in the United States.” Although the Court reserved the possibility that such status checks might raise other constitutional problems, they were not preempted by federal immigration law.

Thank you for the explanation of what the Supreme Court did and didn't do. More and more examples of Republicans who do not want the rule of law, who want to weaken and impoverish Federal laws while ushering in chaos. It's very clear that Republicans cannot govern and, therefore, want to get their positions implemented through minority rule power grabs. All of this in addition to them refusing to work together with Democrats to pass immigration legislation because Trump said not to cooperate. Make certain everyone you know is registered to vote and that they do vote in November. Take deep breaths, get plenty of rest and move forward on protecting democracy.

Excellent summary (as usual - I admire your ability to churn out at a good clip consistently high quality analysis, both legal and historic).

This Texas situation is redolent of the 1820-1861 history of tensions leading to the Civil War. Governor Abbot's neo-Calhounist rhetoric has been as defiant as any exhibited by fire-breathing secessionists of that period. A difference is that we have no Websters or Lincolns to clarify the centrality of the Constitutional issues at stake. It is an incipient crisis that presents a very delicate issue for the sitting President, particularly given the extent of the passions and the disinformation/misinformation fog that have settled over immigration law and policy. No faithful president can permit local or state authorities to actively, by threat of force, interfere with execution of federal court orders or the carrying out by federal officials of their lawful functions. On the other hand, much of this is political hot air exhaust without overt action. There's no question that an Abbott or a Patrick or a Trump etc. can garner considerable public support form a citizenry not sensitive to the potential harm to the constitutional foundations of the Republic caused by the notion that a state my unilaterally determine the final content of federal policy on core, enumerated federal functions.

I've argued Supremacy Clause issues at all levels of the federal court system. In no other area of my practice and career do I feel that I have a profound debt to the earlier champions of preservation of the Union. I hope the absolutely wretched, hyper-ventilated political atmosphere of our time does not distort the outcome of this issue and that, to the extent these issues are reviewed by the Supreme Court, the Court can be unanimous or nearly so in issuing clear, durable reminders of why some subject matters must be left to the federal government and with clear authority to brush aside local or state impulses to displace federal control.