23. The Resignation of Justice Fortas

The only scandal-impelled resignation of a Supreme Court Justice in the Court's history provides a revealing yardstick against which to measure current events

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

As last week’s regular and bonus issues covered in detail (and predicted), the biggest news to come out of the Court involved the two “administrative” stays that Justice Alito issued Friday afternoon, temporarily freezing lower-court rulings that would have severely restricted access to mifepristone beginning at midnight (CT) Saturday morning. Alito’s rulings pause the lower-court rulings only until 11:59 p.m. (ET) this Wednesday.1 Thus, we should expect a ruling from the full Court on whether it will stay the lower-court rulings indefinitely pending appeal before Thursday (most likely, late in the day Wednesday).

The Court also issued a single ruling in an argued case on Friday, holding, in Axon Enterprise, Inc. v. FTC, that when litigants want to challenge the constitutionality of how SEC or FTC administrative law judges are appointed, they can bring those claims in federal district courts without first raising them before the agencies. It’s a technical ruling about statutory preclusion/exhaustion, but it also makes it easier for litigants to bring some of the very challenges to the contemporary administrative state that are in vogue with the Court’s current majority. That may explain why the result was unanimous—and why every Justice except Gorsuch joined in Justice Kagan’s majority opinion.

Axon brings to a paltry total of nine the number of signed rulings in argued cases so far this Term (by this point last Term, the Court had handed down 15 such rulings, which was itself unusually slow). Indeed, because the Axon ruling resolves two separate appeals, we now expect one fewer decision on the merits this Term.

Beyond the mifepristone mess, the Justices denied two other applications for emergency relief—refusing to block Florida’s execution of Louis Gaskin; and refusing to freeze a settlement between the Department of Education and student loan borrowers in a suit arising out of predatory behavior by for-profit colleges (three of which had asked the Justices to put the settlement on hold).

In addition to the denouement of the emergency applications in the mifepristone case, the Court has a busy week of regular business ahead. We expect a regular Order List at 9:30 ET today, followed by the beginning of the April argument session. And decisions in one or more argued cases are expected both tomorrow and Wednesday at 10:00 ET.

We’re starting to get into the busy period for the Court, and with the Justices so far behind in handing down merits rulings (and taking up cases for next Term), the next two months are figuring to be even busier than usual.

Finally, stories about Justice Thomas’s … less-than-ideal … financial reporting and disclosure habits continued to pile up last week, including a follow-on report from ProPublica about Thomas’s failure to disclose the proceeds from the 2014 sale (to Harlan Crow) of his mother’s home and two adjacent properties; and a Washington Post story on Sunday about Thomas continuing to claim income from a real estate firm that has long been defunct. The pattern of behavior may seem especially troubling in light of this not being Justice Thomas’s first time facing similar charges; in both 2011 and 2020, Thomas was required to retroactively amend a whole bunch of financial disclosure forms to accurately reflect information he had previously failed to disclose (suggesting, in the first episode, that he had not properly understood the filing requirements).

The One First Long Read: Justice Fortas

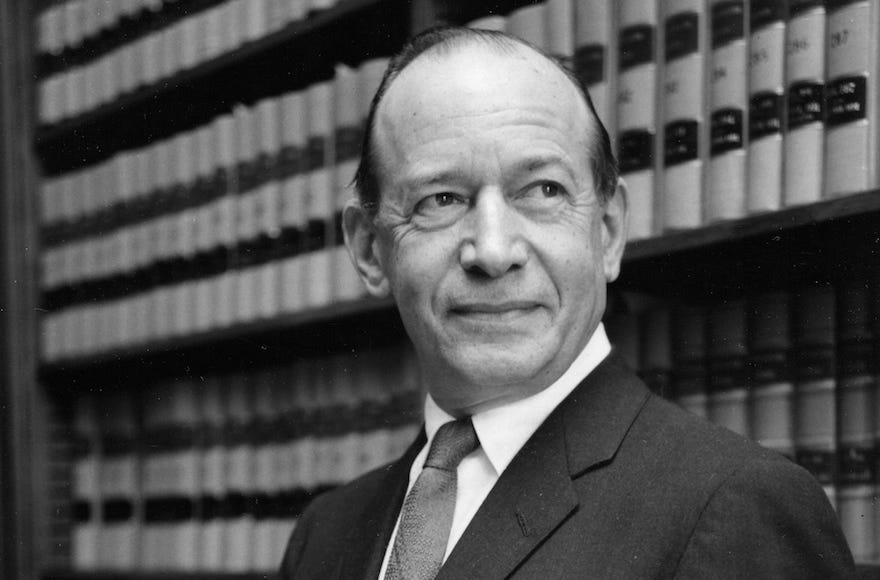

On May 14, 1969, Justice Abe Fortas resigned from the Supreme Court—less than four years after his October 1965 appointment. (That date was the last day, through the present, on which a majority of the Justices had been appointed by Democratic presidents.) To understand why Fortas was all-but forced to resign, and what (if any) yardstick his resignation provides against which to measure current events, we have to go back one year earlier—to his nomination to succeed Earl Warren as Chief Justice.

On June 13, 1968, Warren announced his intention to retire from the Supreme Court “effective at [President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s] pleasure.” 13 days later, Johnson wrote to Warren that he “accept[ed] your decision to retire effective at such time as a successor is qualified,” and he nominated Fortas as Warren’s putative successor (and Fifth Circuit Judge Homer Thornberry to fill Fortas’s seat).

Just about everyone involved had miscalculated badly. By June 26, Johnson was a lame duck; he had announced on March 31 that he would neither seek nor accept the Democratic nomination to run for a second full term, and thus he simply did not have the same influence over Senate Democrats that he had exercised for most of the previous four-plus years. And although Johnson believed that the nomination of his old friend Thornberry would placate conservative Southern Democrats opposed to the more liberal Fortas, Thornberry was instead seen, like Fortas, as being too close to Johnson—amplifying charges of cronyism by a lame duck. (Clark Clifford had privately urged Johnson to nominate a moderate Republican alongside Fortas; history might well have been different if LBJ had listened.) Republicans, sensing a serious chance of recapturing the White House that November (by late June, the Democratic field was in a fair amount of chaos following the assassination of Bobby Kennedy), dug in their heels—insisting, among other things, that Fortas take the unprecedented step of testifying in support of his nomination.

Fortas also miscalculated by accepting the invitation (the two prior sitting Justices to be nominated to the Chief Justiceship, Edward Douglass White and Harlan Fiske Stone, had refused to testify). The four-day hearing not only put him at loggerheads with both Republicans and conservative Democrats over some of the Warren Court’s more controversial decisions (especially when it came to pornography), but it also brought out new details about just how close his personal connection was to Johnson, and how often he continued to informally consult with Johnson even as he was sitting on the Court. Fortas thus got tagged with both the full criticisms of the Warren Court and growing opposition to the lame duck President Johnson.

But the real nail in the coffin for Fortas’s nomination was the revelation that he had received $15,000 to teach a seminar at American University’s Washington College of Law in 1967. (At the time, the salary of an associate justice was $39,500; Congress would raise it to $60,000 in 1969.) The payment itself was not unlawful, but part of the money that the University had used to fund the seminar had been raised from private donors, at least some of whom had interests in litigation before the Court (and who were well aware of Fortas’s … frustrations … with the sharp salary decrease from his previous salary as a law firm partner when he ascended the bench). When this came out during the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings, the remaining liberal Republican support for Fortas collapsed—effectively dooming his nomination.

On October 1, 1968, Fortas “won” a cloture vote by only a 45-43 vote. The writing was on the wall, and he asked Johnson to withdraw his nomination the next day. Johnson begrudgingly acquiesced later that night, and vowed to let the next President fill Warren’s seat.

Matters might have ended there, but for the persistence of two other actors: The Nixon administration (once it came to office in January 1969), and William Lambert, a reporter for Life magazine. Both had heard rumors about Fortas’s association with Louis Wolfson—a wealthy financier who had been convicted in 1967 of conspiracy to violate federal securities laws and of selling unregistered stock. Wolfson had been one of Fortas’s clients prior to the latter’s elevation to the Court, and their relationship had … continued after Fortas’s 1965 confirmation, with Fortas continuing to provide informal advice (but no formal representation) to Wolfson about his impending troubles with the SEC.

Critically, as would later emerge, as part of their relationship, Fortas had agreed to enter into a financial arrangement with Wolfson wherein the latter would pay him $20,000 annually in exchange for unspecified services and assistance (and would pay Carolyn Agger, a prominent tax lawyer and also Fortas’s wife, the same annual sum upon the Justice’s death if she survived him). At least at the time, such a payment was neither unlawful nor prohibited by the then-prevailing standards for judicial ethics. But given Wolfson’s impending troubles, it was unseemly, to say the least. And yet, although Fortas accepted a single payment from Wolfson in January 1966, he returned it that December (at least in part because one of his current law clerks was deeply troubled by the specter it created)—and never took another penny. There is some evidence that Fortas spoke to Johnson at some point about a potential pardon for Wolfson, but nothing to suggest any kind of quid pro quo.

Nevertheless, when Lambert broke the story of Fortas’s relationship with Wolfson on May 5, 1969 (at least largely based on leaks from the Nixon Justice Department), it was a bombshell. The Nixon administration, which had already picked up the scent, went even further, with Attorney General Mitchell threatening to investigate Fortas (and convening a grand jury to investigate an unrelated claim that Agger had obstructed the government in a price-fixing case). Shortly, Democratic senators who had previously supported Fortas began to publicly call for his resignation.

But perhaps the critical pressure came not from outside the Court, but from within it. Although some of Fortas’s colleagues (including Hugo Black, who had come to be one of his foremost rivals within the Court) urged him to stay the course, Chief Justice Warren privately told Fortas that he should resign for the good of the Court—and to potentially stave off impeachment proceedings. (Warren had agreed to a private meeting with Attorney General Mitchell on May 7, at which the latter had laid out what was portrayed as an “ongoing” investigation into Fortas—rather than admitting that the Wolfson matter was where it started and ended.)

As Laura Kalman writes in her excellent 1990 biography of him, Fortas feared not only for his (and Agger’s) own future, but also that the Nixon administration’s feeding frenzy would extend to ensnare other Justices. On May 14, 1969, Fortas transmitted his brief letter of resignation to President Nixon, alongside a longer letter to Chief Justice Warren memorializing his version of events. As Kalman notes, he told a friend that he “resigned to save Douglas.”

In retrospect, Fortas’s relationship with Wolfson was undoubtedly inappropriate. But it also seems to pale in comparison to some of the more recent reporting regarding Justice Thomas in its frequency, its specifics, and the pure cash benefit he derived from it. (Thomas is also subject to far stricter financial disclosure requirements and ethical constraints, some of which were a reaction to Fortas’s case.) Indeed, Fortas returned the only money Wolfson had given him long before the arrangement became public; and his real misstep was in continuing to counsel and advise Wolfson after being elevated to the Court—a breach of norms, protocol, and common sense, but not of any more formal prohibition on the Justices’ behavior that was then in effect.

In that respect, perhaps the Fortas episode might have ended differently had he not just gone through a failed nomination to be Chief Justice. But with his close (and ongoing) personal and professional relationship with Johnson and the private funding for his American University seminar still fresh in everyone’s minds from the previous year, the Wolfson scandal was just a bridge too far.

A reader not previously familiar with the Fortas affair might be surprised that this is it; an inappropriate relationship with a shady financier from which Fortas received no ultimate financial benefit; a lavish payment for a seminar where the real problem was not the amount, but who funded it; and a far-too-close relationship with the sitting President even while he was sitting on the Court. That was enough to lead Fortas’s own Chief Justice, an ideological ally and personal friend, to persuade him to resign in 1969 knowing full well that the vacancy would be filled by a President of the opposite party (Fortas’s seat would eventually be filled by Justice Harry Blackmun).

The contrast with today is … striking.

SCOTUS Trivia: Failed Chief Justice Nominations

Fortas’s failed 1968 nomination to replace Warren as Chief Justice remains the only failed nomination for the Court’s center seat since 1874, when President Grant offered the position (which had become vacant upon the May 1873 death of Salmon Chase) to seven different candidates, and formally nominated three: New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, who declined; Attorney General George Williams, who withdrew in the face of significant Senate opposition; and Morrison Waite, who was ultimately confirmed. Of the 11 men who have since been nominated to serve as Chief Justice, all but Fortas were confirmed.

But the only time in the Court’s history in which the Senate has ever formally rejected a Chief Justice nominee was in 1795, when the Senate voted 14-10 to decline to confirm John Rutledge (largely in response to intemperate public remarks Rutledge had made in opposition to the Jay Treaty). What’s especially remarkable about the rejection of Rutledge is that he was already serving as Chief Justice when it happened, having received a recess appointment from President Washington four months earlier.

I’ll save for a future issue the strange-but-true history of recess-appointed Supreme Court Justices (and the open question of whether the practice squares with Article III’s mandate that Justices keep their offices during “good behavior”). For now, I’ll just note that, long after Rutledge, the most recent Justice to receive a recess appointment was Potter Stewart in 1958; and the most recent Chief Justice to receive one was Earl Warren, in 1953.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

Although some Justices prefer to issue indefinite administrative stays, the deadline from Alito was not unusual for him; he imposed an even tighter deadline in August 2021 when the Biden administration sought to freeze a nationwide injunction against its rescission of the “remain in Mexico” asylum policy.

"The contrast with today is . . . striking." Striking indeed. Thomas must resign for the good of the court and the nation. But he won't - he's already shown his contempt for the rules, so he will feel no obligation to, and few (if any) within the GOP will pressure him will do so. He's a powerful reminder that the Republican party is broken and has been broken for a long time.

Thank you for your column. I am old enough to remember the event. I kept trying to figure out what Fortas did wrong, and I am still waiting. He resigned from the court to prevent a purge. He to use a phrase "fell on his sword" for the good of the court. He had a case of his client come to the court. He properly recused himself. If he had ruled on it, that would be improper. A lesson to be learned from those who talk about the politics of the court.