211. Making Sense of the Tariffs Ruling

Friday's 6-3 ruling reflects an emphatic repudiation of a specific claim of delegated statutory authority by the Trump administration. Folks should be wary about reading it as more—or less—than that.

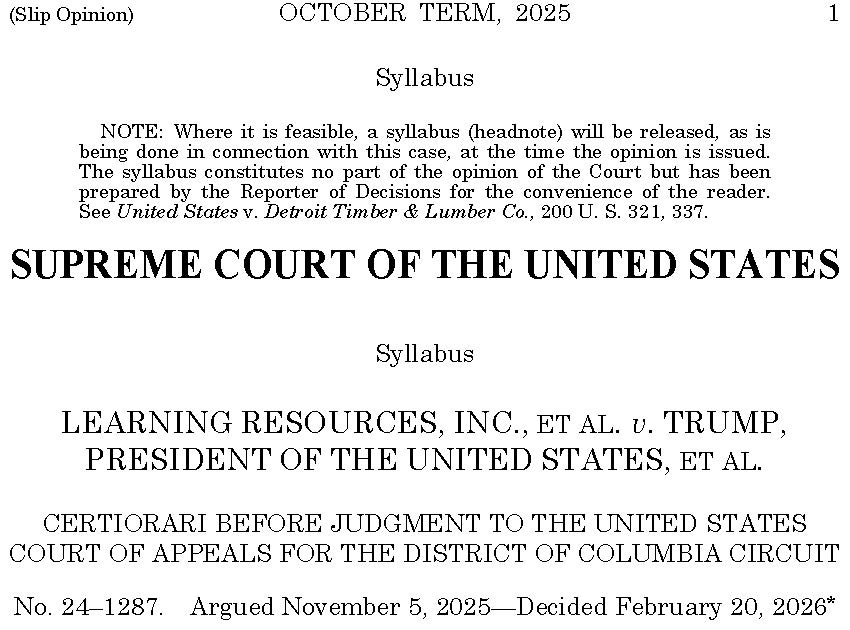

By now, you’ve no doubt seen the headlines about Friday morning’s Supreme Court decision in Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump—in which a 6-3 majority held that the reciprocal and fentanyl tariffs imposed by President Trump were unlawful, because Congress had not authorized them in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA).1 The three Democratic appointees, Justice Gorsuch, and Justice Barrett joined Chief Justice Roberts in holding that IEEPA doesn’t authorize the tariffs, although they split (in ways I’ll get into below) as to why. You’ve also probably seen some of the commentary out there—from the Adam Liptak’s suggestion that the ruling reflects the Court’s “Declaration of Independence” from Trump to Jack Goldsmith’s take that the ruling (and President Trump’s angry but acquiesing reaction to it) “elevated the Court and was a remarkable testament to its power.”

Maybe this isn’t a very exciting or sensational take, but I had a far more modest reaction to the ruling. It is, unequivocally, a sweeping repudiation of President Trump’s ability to use IEEPA for tariffs (or anything else that the 1977 statute doesn’t directly contemplate). That is, in my view, a very good thing—both on the merits of the specific legal question presented in the case and as evidence that there are at least some lines this Court won’t cross, even in cases arising out of Trump administration policies.

But … that’s it. I think it’s wrong to celebrate the ruling as some kind of turning point in the Court’s relationship with Trump, just as I think it’s wrong to denounce it as a cynical move by justices concerned primarily about the economy as opposed to about fidelity to neutral legal principles. This was not a case about the President’s constitutional power, but about the meaning of a 49-year-old statute. And although IEEPA is triggered by the President’s declaration of an amorphously defined “emergency,” the question before the Court wasn’t whether this was an emergency (which would bear on lots of other disputes involving the Trump administration), but rather whether, even in emergencies, the statute authorizes tariffs. Holding that the answer is “no” doesn’t tell us anything especially important about executive power in general, or even about the President’s powers under statutes other than IEEPA.

In the same vein, I think it’s wrong to hold Friday’s ruling out as somehow absolving the Court of its deeply problematic behavior on Trump-related emergency applications, just as I think it’s wrong to see it as auguring a shift in how the justices will approach those cases going forward. As I’ve suggested before, although one reading of the Court’s behavior on emergency applications is that it’s in the bag for Trump, there’s an equally plausible reading in which it isn’t, and is granting emergency relief in so many of these cases for deeply problematic reasons unrelated to a conclusive view of the merits. If that’s accurate, then there’s every reason to treat the Court’s “merits” cases involving Trump (of which this is the first) as belonging to an entirely different category from the emergency applications.

This is all a long way of saying that two things can be true: (1) the tariffs ruling makes clear that the Court is not going to rule reflexively for the Trump administration in every case (a point for which we already had data); and (2) there’s still plenty of reason to be concerned about its overall behavior when Trump is one of the parties at bar.

That’s my top-line take. Here are few more specific reactions:

I. The Fight Over What the Major Questions Doctrine … Is

Although there was a clear majority for the proposition that IEEPA doesn’t authorize President Trump’s tariffs, there’s a pretty firm 3-3 split among the six justices in the majority about how they get there. Three of the justices (the Chief, Gorsuch, and Barrett) relied on the “major questions doctrine,” the (controversial) idea that Congress must legislative with specificity when it comes to questions of “vast economic or political significance.” For the three Democratic appointees, Justice Kagan kept up their consistent view that the MQD is … not a thing (but reached the same result through more traditional methods of statutory interpretation).

What’s interesting to me here is not the daylight between the two three-justice blocs, but the daylight between the Chief and Gorsuch (especially Gorsuch), on one hand, and Justice Barrett, on the other, both of whom wrote separately. This isn’t the first time that Justice Barrett has suggested that the MQD does less work relative to preexisting principles of statutory interpretation than the other Republican appointees, but it’s especially visible here. (For Gorsuch, the MQD is more muscular at least in part because he sees it as a deriviate of the constitutional non-delegation doctrine—which he views as far more robust than just about all of the other justices.)

I have no doubt that forests will be felled by the law review articles and symposia saying more about this very specific debate. Its broader significance, in my view, is that it suggests that there’s less daylight between Barrett and the Democratic appointees in (politically charged) pure statutory interpretation cases than there might be between her and the other Republican appointees. Indeed, her concurrence and Justice Kagan’s concurrence in the tariffs ruling have quite a lot in common. That’s probably not a big deal for future Trump cases entirely about statutory interpretation—where we may well expect this lineup to recur. But it could matter a lot in the next administration—where Barrett may be the fourth vote in support of executive branch interpretations of ambiguous statutes. The question then will be who, if anyone, would be the fifth vote. If today’s ruling sheds light on that answer, the most plausible answer is the Chief Justice (at least if the next president is a Democrat).

II. The Gorsuch/Kavanaugh Flip

That leads me to the “flip” between Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh. For what little it’s worth, I had thought that Gorsuch effectively telegraphed his position at the oral argument in November. The more surprising vote here (to me, anyway) is Kavanaugh’s. There’s quite a lot to say about his “principal” dissenting opinion (and I’ll say some of it below). For now, it seems worth at least asking whether this signals that, in counting votes in Trump-related cases, Gorsuch is now more in the Court’s “middle” than his fellow Georgetown Prep alum.

To be clear, I think this is a question that’s a lot more about Kavanaugh than it is about Gorsuch. At least looking at the data, there’s only one visible example of Kavanaugh joining the Democratic appointees in a case in which Gorsuch didn’t (Trump v. Illinois)—and now there’s one visible example in the other direction. So I think it’s too soon to view them as flipping in general. But what can’t be denied, based on both the emergency application rulings to date and Friday’s tariffs ruling, is that it the most likely votes to join the Democratic appointees in Trump cases, by far, are (and have been) the Chief Justice and Justice Barrett—with growing daylight between those two and Gorsuch and Kavanaugh. Compared to those who suggested, back when Kavanaugh was nominated in 2018, that he’d be likely to vote most closely with Chief Justice Roberts, the shift is … striking.

III. The Dissenters’ Hypocrisy

And then there’s the substance of the dissenting opinion. There’s more to say about Justice Kavanaugh’s 63-page opinion than I have room for here, so I’ll reduce my reaction to two quick points:

First, the heart of the dissent’s argument is that the major questions doctrine doesn’t apply to foreign affairs or national security cases. However attractive that may sound in the abstract, it may be worth reminding readers of the specific statute that the Court confronted in the student loan debt forgiveness cases—the HEROES Act of 2003. That statute was a post-9/11 measure designed to authorize the Secretary of Education to take certain extraordinary measures “as the Secretary deems necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency” (emphasis added). And President Biden’s program was specifically pinned to the national emergency declared in response to the COVID pandemic. One must do more than just wave their hands to explain why the major questions doctrine applied to (and invalidated) that “national security” measure, but not this one. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, all three of Friday’s dissenters were in the majority in Biden v. Nebraska.)

Second, Justice Kavanaugh’s dissent closes by worrying about the costs (the “serious practical consequences”) of the Court’s ruling, especially the “mess” surrounding the question of whether those who paid the tariffs are, and ought to be, entitled to refunds (more on this in a moment). But to what end? If consequentialism is supposed to factor into how we interpret statutes, well, there are some other decisions with which we might quibble. If the point is that those costs are too steep for the Court to intervene now, well, that would lead to the rather stunning result that, the greater the impact of a President’s unlawful behavior, the less ability courts have to strike it down. The opinion doesn’t identify the relevance of those concerns, but it’s a striking note on which to end a dissent that was putatively about neutral legal principles—and not in a good way.

IV. So What About the Remedy?

The $140-billion question, of course, is what happens now. A lot of commentators have expressed surprise that the Court didn’t reach and address the remedy, but (1) the lower courts didn’t either; (2) it was, at best, thinly briefed in the Supreme Court; and (3) it barely came up at the oral argument. Indeed, there are plenty of examples, throughout history, of the Supreme Court handing down a ruling likely to produce significant economic effects—and then leaving it to other actors to sort out how to ameliorate those effects.

The problem here is that, historically, that other actor was Congress. In the 1940s, for instance, Congress responded to a trio of Supreme Court rulings potentially creating billions of dollars of retroactive back-pay liability by … extinguishing the claims for back pay. In 1982, when the Supreme Court invalidated the entire bankrupcy court system, it stayed its ruling for 3.5 months expressly to buy time for Congress to come up with a fix. And there are other examples, too. And so, measured against the sweep of history, it’s not at all unusual for the Court to leave the remedy question alone even as its ruling seems to open the door to a whole lot of monetary liability on the federal government’s part.

Without a functioning Congress, that onus falls on the lower courts—at least in the first instance. And without getting too far into the weeds, let me just say that it’s not an easy set of questions. Does everyone get a refund—not just importers who paid these unlawful tariffs, but consumers who paid a higher price for goods as a result? If not, do all importers get a refund, or only those who had/have already sued the government seeking their money back? And what about the Customs and Border Protection process for processing refunds of over-paid tariffs? Does that apply here, too? What if that agency is … entirely unprepared … for the flood of claims to come? It certainly seems possible that lower courts faced with these questions will just throw their hands up and give the ruling only prospective effect. It’s also possible that they’ll try to come up with some kind of compromise. The key, for now, is that it shouldn’t be up to the lower courts—and those who are frustrated by this reality should place the blame where it belongs, not with the Supreme Court for reaching out to resolve that issue now, but with Congress for abandoning its responsibility for addressing these kinds of (messy) public policy problems.

As for the tariffs themselves, it’s always been true that President Trump could have relied upon other statutes for at least some of them—statutes that prior presidents (including, it should be noted, first-term President Trump) successfully relied upon to impose narrower tariffs in other contexts. Those statutes are far more specific than IEEPA, and have more robust substantive and procedural constraints (which is why Trump didn’t use them here). But when President Trump imposes a handful of new tariffs and claims that he’s doing “the same thing” (as it seems he’s already doing by purporting to impose a 10% tax on all imports), all I can say is that folks would be well-advised to not take the parity claim at face value. Just like President Biden was within his rights to attempt to find a different statutory rationale for the student loan program after the Court rejected the HEROES Act, so too, here. And although Justice Kavanaugh’s dissent on Friday seemed to suggest that this is yet another reason to be critical of the majority, I see it as further evidence of the Court doing … what the Court does—no more, and no less.

There will surely be more to say about this ruling in the days and weeks to come—including President Trump’s … not exactly measured … reaction to it. But it’s Friday night, and life (and my 10-year-old’s volleyball practice) goes on, so we’ll hit the pause button here. We’ll be back with our “regular” coverage of the Court on Monday morning.

In the interim, if you’re not already a subscriber, and have found this discussion useful and/or interesting, I hope you’ll consider subscribing (and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit):

Stay safe out there, y’all.

It’s more fun if you pronounce it the way Bobby Chesney and I did on the National Security Law Podcast: “eye-EEE-pah.”

Cogent analysis as always, thank you. I particularly liked the (perhaps too polite) way you singled out Kananaugh's foray into "consequentialism" as a guide to interpreting federal statutes, which plainly deserves ridicule. That part of his dissent will remain a standing joke in law schools for decades to come.

First, this group of opinions seems to emphasize that we have a very deeply divided Court that will have difficulty deciding difficult cases. This was not a difficult case to decide.

Second, I share the skepticism about MQD and have thought that it was really conceived as a flexible tool to rule for favored policies and against disfavored policies. I am wearily pleased that there was a 6-vote majority to apply roughly the same rules to Trump as the Court applied to Biden.

Steve's pointed comments about abdication by Congress are right on point. Congress has all the authority it needs to eliminate any chaos resulting from this decision and to create more clear rules surrounding the President's tariff authority. As has been made clear by this episode, laws passed by past Congresses on the subject are a complete mess.