195. The Immigration Detention Flood

The Trump administration's attempt to quietly—but massively—expand who can be detained pending their removal has been met with overwhelming pushback from a remarkably large number of district courts.

Welcome back to “One First,” a (more-than) weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court and related legal topics more accessible to lawyers and non-lawyers alike. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support—and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks:

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current issues, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

I wanted to use today’s “Long Read” to write about an issue that, at least in my universe, hasn’t gotten a lot of public attention—but that may well be one of the more quietly important legal stories of the year: The role federal district courts are playing in pushing back against a massively significant change to immigration detention policy that the Trump administration quietly attempted to implement back in July.

In a nutshell, the executive branch has radically expanded its interpretation of which non-citizens can be arrested and detained without bond pending their removal proceedings—a move that has exposed hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of individuals already living inside the United States to immigration arrest and detention to which they would not realistically have been subject prior to this summer, and with no right to seek release once they’ve been arrested. Many of those arrests have taken place at ICE facilities or courthouses when these same individuals have appeared for regular check-ins or for the next steps in their asylum applications. But regardless of where these arrests are taking place, it’s safe to say that this quiet attempt to expand what’s often shorthanded, however inaccurately, as “mandatory detention” is directly connected to many of the arrests we’re seeing during ICE raids in U.S. cities.

The Trump administration’s new interpretation of a 29-year-old statute, in turn, has been rejected by a truly staggering array of federal district courts across the country. According to Politico’s Kyle Cheney, since July,

At least 225 judges have ruled in more than 700 cases that the administration’s new policy, which also deprives people of an opportunity to seek release from an immigration court, is a likely violation of law and the right to due process. Those judges were appointed by all modern presidents—including 23 by Trump himself—and hail from at least 35 states . . . . In contrast, only eight judges nationwide, including six appointed by Trump, have sided with the administration’s new mass detention policy.

What is striking about this pattern is not just its volume or the scorecard; it’s that the judges in many of these cases are writing thorough, persuasive opinions explaining why the Trump administration is utterly wrong on the law—including an especially strident ruling from Judge Lewis Kaplan in the Southern District of New York just last Wednesday. Kaplan appended to his 33-page decision a list of more than 350 of additional rulings by his district court colleagues. And although the litigation has proceeded at a retail, case-by-case level to date (hence the high number of cases), last Tuesday, Judge Sunshine Sykes in the Central District of California certified a nationwide class action at least for purposes of declaratory relief against the policy—which may accelerate how quickly this issue moves to the courts of appeals and, inevitably it seems, to the Supreme Court.1

I’ve written before about the role federal district courts have played in issuing coercive relief against Trump administration policies over the past 10 months. These cases have not been part of the dataset my research assistants and I have maintained because they have been, to date, individual requests for release from detention rather than lawsuits seeking coercive relief against the policies themselves. But excepting changes to federal criminal sentencing laws, I can’t recall any other example of a federal policy that provoked quite so much litigation in such a short period of time—or litigation in which so many judges from across the geographical and ideological spectrum so overwhelmingly rejected the executive branch’s new interpretation of the relevant statutes. It’s a striking story not just about the Trump administration’s zealotry when it comes to immigration policy, but about the critical role hundreds of federal judges have played in steadfastly holding the executive branch to the law.

But first, the (SCOTUS-related) news.

On the Docket

The Merits Docket

Last week’s regular Order List brought with it the Court’s first two opinions of the term—both of which were “summary reversals” in which the justices reversed a court of appeals at the certiorari stage in an unsigned (“per curiam”) opinion, without hearing oral argument or otherwise conducting plenary review:

In Pitts v. Mississippi, the Court reversed the Supreme Court of Mississippi—which had rejected a Sixth Amendment Confrontation Clause challenge to a Mississippi statute mandating the physical screening of all child abuse victims from criminal defendants during their testimony. As the Court reaffirmed in a five-page opinion, the Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause requires trial courts in those circumstances to make case-specific determinations of whether such screening truly is necessary, regardless of any categorical state law rule to the contrary. There were no public dissents.

And in Clark v. Sweeney, the Court reversed the Fourth Circuit—holding that it had wrongly granted post-conviction habeas relief to a Maryland prisoner based upon an argument that the prisoner had failed to fully and fairly present himself (in a case in which one of the jurors had visited the crime scene without authorization and had subsequently been dismissed). The only issue the prisoner had preserved, the Court held in a four-page opinion, was whether his trial counsel had rendered ineffective assistance by agreeing to allow the case to proceed to a verdict once the juror was dismissed.

When Will Baude coined the term “shadow docket” in 2015, he was specifically responding to a significant uptick at that moment in these kinds of certiorari-stage “summary” rulings. They had rather petered out over the ensuing decade, so it will be interesting to see if the two rulings last Monday end up as outliers, or as a sign that more of these rulings are incoming. Time will tell.

The only other especially noteworthy developments in last Monday’s Order List were the separate opinions respecting the denial of certiorari in Beck v. United States. The issue in Beck is the so-called “Feres doctrine,” an (entirely atextual) interpretation of the Federal Tort Claims Act adopted by the Supreme Court in 1950 that bars any and all lawsuits by military servicemembers against the federal government for torts “arising out of, or incident to” their military service. Justice Thomas has long been (quite rightly, in my view) a staunch critic of Feres, and has been calling, for years, for the justices to revisit that precedent. Alas, he seems to once again have come up short. Although Justice Gorsuch also noted that he would have voted to take up this case, Justice Sotomayor penned a separate “statement” suggesting that it should be up to Congress to fix the mess the Court created—“out of respect for the Court’s rules of stare decisis, and in recognition of the reliance interests that Feres has generated.” Of course, it’s hard to imagine any Congress, let alone the current one, making it easier for servicemembers to sue the federal government. That’s why Feres, handed down just four years after the FTCA was enacted, was so problematic in the first place.

The Emergency Docket

It was a surprisingly quiet week with respect to emergency applications. The only action of note from the full Court came Wednesday—when the Court issued an order … declining to act … on the Trump administration’s request to freeze a lower court ruling that had blocked the attempted removal of Shira Perlmutter as the Register of Copyrights. The Court’s order, from which only Justice Thomas publicly dissented, noted that the application is being deferred pending the Court’s consideration of Trump v. Slaughter (set to be argued next Monday) and Trump v. Cook (set to be argued in January). Frankly, I don’t get it. The underlying question in Perlmutter is a very specific, statutory question (is the Library of Congress an “executive agency” for purposes of the Federal Vacancies Reform Act) the answer to which won’t be implicated at all in those two other cases. And although the second question the justices asked the parties to address in Slaughter (what’s the remedy for federal officers who are unlawfully removed) could obviously affect other cases, Perlmutter is still … in her job, and doesn’t need to be reinstated by a court. This last point, of course, means that the ruling is effectively a loss for the Trump administration. But it’s not clear to me why there wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) have been five votes to just say that now.

The Week Ahead

This morning kicks off a busy week at the Court—with the beginning of the December argument session starting at 10. We also continue to wait for the Court to rule on the two especially high-profile emergency applications that remain pending—Texas’s application in the Texas redistricting case; and the Trump administration’s application in the Illinois National Guard case.

As has so often been true with the Supreme Court this year, there’s a lot going on.

The One First “Long Read”:

Mandatory Detention and the Lyons Memo

To understand the flood of immigration detention cases currently inundating the federal courts, it may be helpful to start with a brief background on immigration detention. I’ll also refer folks who’d like even more detail to this helpful 2019 Congressional Research Service report.

Background

In particular, three points seem especially foundational here.

First, the general immigration detention statute, section 236(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. § 1226(a)), provides rules for the arrest and detention of any non-citizen “pending a decision on whether [they are] to be removed from the United States.” But detention under section 236(a) comes, among other things, with a right to a bond hearing (based upon a showing that the individual poses no danger to others; security threat; or flight risk) and eligibility for parole—denials of both of which are subject to judicial review. What’s more, detention under section 236(a) has always been understood to be discretionary—meaning there is no requirement that individuals subject to detention under that provision actually be detained.

Thus, as Judge Kaplan put it last week, “Section 236, since a 1996 amendment, has given immigration authorities essentially two options at the outset of removal proceedings. One option is to keep the noncitizen in custody throughout the proceedings. The other option is to release the noncitizen on bond or parole.” For a host of reasons, the norm, historically, has been to choose the latter—especially for those individuals who have committed no crimes, and who are subject to removal only because they are present in the United States without legal authorization. Those individuals will usually be entitled to release on bond—which, for obvious reasons, has led the executive branch to not prioritize arresting and detaining them in the first place.

Second, and in contrast, there are a handful of more specific “mandatory” detention statutes, which, at least in theory, require the detention of individuals who meet the more specific statutory criteria. The one that is especially relevant here is section 235(b), codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1225(b). That provision actually includes two separate authorities. Section 235(b)(1) is for non-citizens stopped at (or near) the border who are “inadmissible”—and who are subject to “expedited” removal “without further hearing or review unless the alien indicates either an intention to apply for asylum . . . or a fear of persecution.” (The grounds on which someone can be “inadmissible” are a lot more specific than the grounds on which they can be removable.)

Section 235(b)(2), in contrast, mandates detention for the duration of “regular” removal proceedings “in the case of an alien who is an applicant for admission, if the examining immigration officer determines that an alien seeking admission is not clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to be admitted.” Historically, both parts of section 235(b) have been understood to refer, as the section heading reflects, to “applicants for admission” to the United States, i.e., those stopped either (1) at the border; or (2) within some temporal and geographic proximity to having entered the country without inspection. Those who are inadmissible [section 235(b)(1)] can be placed in expedited removal; those who are not [section 235(b)(2)] must go through ordinary removal proceedings during which they can be detained without bond.

Indeed, when section 235(b)(2) applies, not only is there no statutory right to a bond hearing, but the only mechanism for internal review by ICE (a narrow form of humanitarian parole) is not subject to judicial review, either. Thus, there are massively significant differences between detention under section 235(b)(2) and detention under section 236(a)—including not just the likelihood of detention but also the ability of someone detained under these provisions to challenge the factual or legal basis for that detention, or even to seek release on bond while those proceedings continue.

Third, during both the first and second Trump administrations, the executive branch has separately tried to expand the category of individuals subject to expedited removal (and mandatory detention under section 235(b)(1)) based upon when they entered into the United States without inspection. In other words, it’s tried to move the line for who counts as an “arriving alien” to include at least some individuals who have been in the United States for some time. For context, in 2004, the Bush administration had (controversially) interpreted that category to include those stopped at the border or those apprehended (1) within 100 miles of the border and (2) within 14 days of entering the country without inspection. That was a big enough move, but that was the understood (and judicially sustained) limit on who could be subjected to “expedited removal” for decades.

The Trump administration has since sought to expand that category dramatically—to include anyone found anywhere in the United States who cannot prove their continuous presence in the United States for more than two years (the statutory maximum Congress authorized in 1996). But that attempted policy shift was blocked by a D.C. federal district judge on August 29—primarily on the ground that it likely violates the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment by depriving those with significant connections to the United States of a meaningful opportunity to challenge the basis for their expedited removal. Just last Monday, the D.C. Circuit, by a 2-1 vote, denied in relevant part the federal government’s application for a stay of that ruling pending appeal.

***

There’s a lot of complicated immigration law here, and I’m already giving short shrift to some of the nuances. (The American Immigration Council has published a fantastic practice advisory that goes into much more detail for those who are so inclined.) The key for present purposes is that, prior to the July 8 detention policy shift, even the Trump administration’s view had been that, once an individual had been continuously present in the United States for at least two years, they were no longer subject to expedited removal as if they were an “arriving alien” under section 235(b)(1)—and the “ordinary” immigration process [section 236(a)] would otherwise apply barring special circumstances. Those individuals could still be subject to mandatory detention if they fell into one of the specific categories of such detention (e.g., certain individuals convicted of crimes or for the 90 days preceding the effectuation of a removal order). But absent those special circumstances, individuals who had been continuously present in the United States for at least two years (under the Trump administration’s contested view) or even just two weeks (under the Bush administration’s view) were subject to arrest and detention only under the more generous, bond-eligible, discretionary authority of section 236(a).

I’m not aware of any specific data on what percentage of the total population of non-citizens living today in the United States without inspection has been continuously present in the United States for at least two years. But a 2024 DHS report found that 79% of undocumented immigrants had been present in the United States since before 2010. It stands to reason that the percentage of that population who have been in the United States since at least November 2023 is … much higher. In other words, there are a lot more undocumented immigrants who have been continuously present in the United States for more than two years than who have not been.

The July 8 Memo and Subsequent Developments

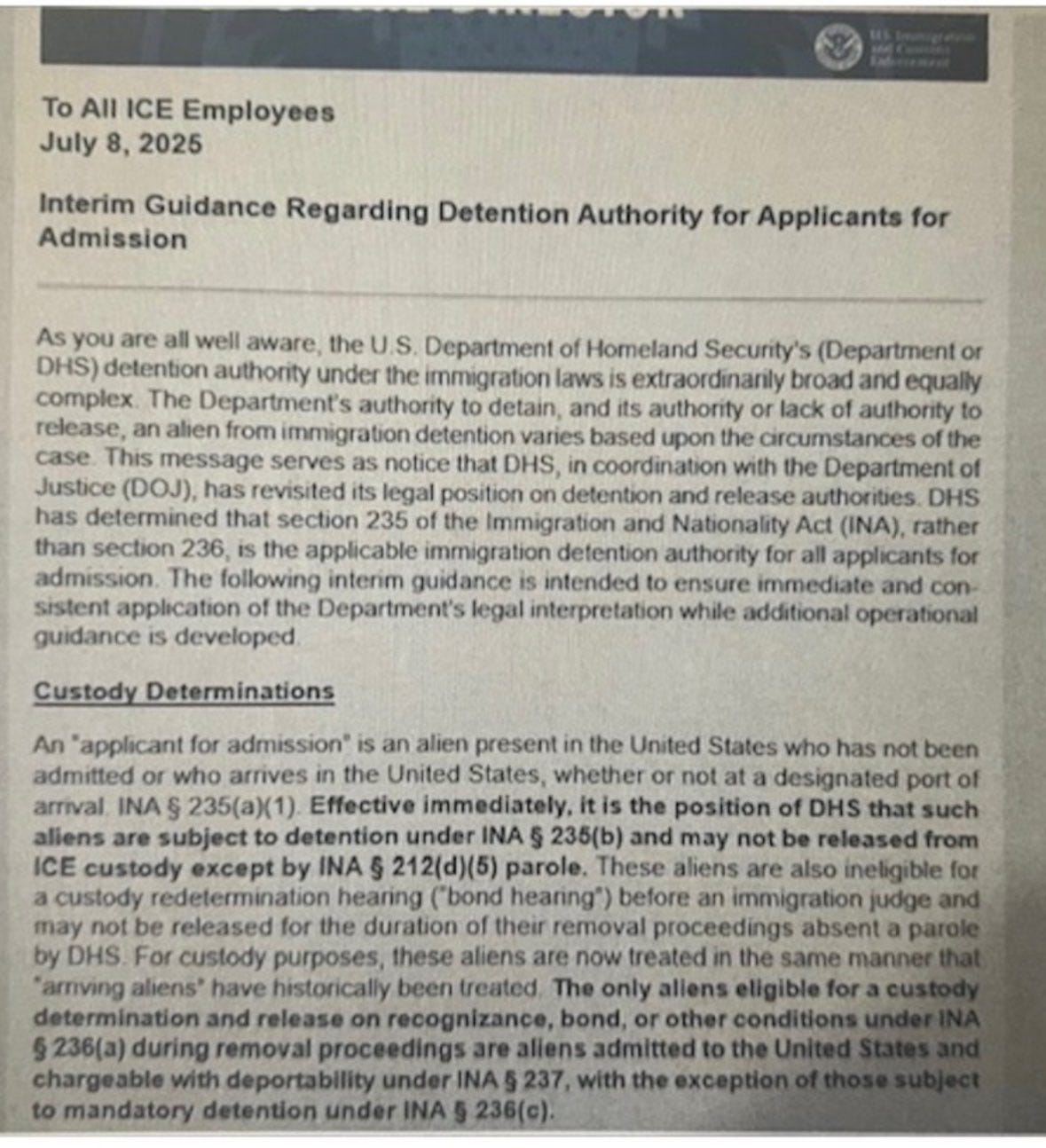

On July 8, Todd Lyons, then the Acting Director of ICE, issued a memorandum titled “Interim Guidance Regarding Detention Authority for Applicants for Admission.” In it, Lyons wrote that “It is the position of DHS that [any non-citizens who entered the United States without being admitted] are subject to detention under INA § 235(b) and may not be released from ICE custody except by INA § 212(d)(5) parole.” To make the point clear, the memo continued, “For custody purposes, these aliens are now treated in the same manner that ‘arriving aliens’ have historically been treated.” The only non-citizens who would still be covered by the “ordinary” detention provision would be those who had been lawfully admitted to the United States upon entry or received some lawful status thereafter, only to have committed some immigration or criminal offense that subjects them to removal.

Just to underscore the point, the Lyons memo effectively subjected to immediate arrest and to mandatory detention pending removal every single non-citizen physically present in the United States who had never been lawfully admitted, no matter how long they have been here or how carefully they’ve followed the law since their arrival. And although initial headlines (e.g., in the Washington Post) highlighted that the memo revoked those individuals’ right to a bond hearing, no less important is the extent to which it subjected them to arrest and detention in the first place—arrest and detention that would not have been a realistic possibility, even if it was formally available, under section 236(a). A non-citizen, for instance, who came to the United States with their parents when they were a child, and who has lived in the country for decades without committing any crimes, is now subject to mandatory detention with no possibility of bond under the July 8 memo; before that, even if the law might have allowed for their arrest and detention, they would almost certainly have been released on bond for the duration of their removal proceedings—assuming the government wanted to remove them in the first place.

Almost overnight, as ICE started implementing the July 8 policy, individuals who, all of a sudden, were subject to arrest and detention under the new interpretation of these 29-year-old statutes brought habeas petitions challenging their detention in the federal district court in which they were held. This led to a remarkable flurry of rulings by federal district judges across the country—as reflected in a public database maintained by the American Immigration Council in conjunction with the University of Iowa immigration law clinic. And the judges in the overwhelming majority of those rulings have concluded that the July 8 policy is unlawful—because section 235(b), by its terms, does not apply to individuals who are not “seeking admission into the country” (because they have already been here for some time). As one district court succinctly put it in August, “someone who enters a movie theater without purchasing a ticket and then proceeds to sit through the first few minutes of a film would not ordinarily then be described as ‘seeking admission’ to the theater.”

Although I could link to any of dozens of these rulings, two especially illustrative examples are last Wednesday’s decision by Judge Kaplan in Manhattan; and a ruling from the previous week by Judge Lynn Winmill in Idaho. As Judge Kaplan concluded, “Requiring the detention of noncitizens like [the petitioner in that case] would be inconsistent with how immigration law in this country long has worked, not to mention the rule of law and basic notions of due process.” And in Judge Winmill’s words,

Since the United States began restricting immigration into this country in the late 19th century, it has distinguished between those noncitizens seeking entry into the country and those already residing within it. Noncitizens “stopped at the boundary line” who have “gained no foothold in the United States,” do not enjoy the same constitutional protections afforded to persons inside the United States. But once a noncitizen enters the United States, “the legal circumstance changes,” for the constitutional right to due process applies to all “persons” within our nation’s borders, “whether their presence here is lawful, unlawful, temporary, or permanent.” This distinction between noncitizens who have entered and reside in the United States and those who have not yet entered “runs throughout immigration law.”

It’s not just that this distinction “runs throughout immigration law”; it’s that it also reflects the more humane reality that, however they entered the United States, those who have lived in the country for years (if not decades), and who have pose no risk to their communities or the country, may lawfully be subject to removal—but they do not pose the same risk justifying aggressive (and expensive) uses of law enforcement resources along the way.

To be sure, there have been a handful of rulings in the other direction—most notably a decision by the Board of Immigration Appeals (which is in the Department of Justice) in September—which, among other things, effectively bars any of the Department’s internal immigration judges from ruling otherwise. Indeed, that’s a big part of why so many of these cases have ended up in federal district court. But the arguments the district courts keep embracing seem pretty straightforward to me, regardless of one’s preferred approach to statutory interpretation. Even the Supreme Court, as recently as 2018, was clear on the core distinction here: “U.S. immigration law authorizes the Government to detain certain aliens seeking admission into the country under §§ 1225(b)(1) and (b)(2). It also authorizes the Government to detain certain aliens already in the country pending the outcome of removal proceedings under §§ 1226(a) and (c).” Indeed.

***

It’s hard to predict exactly what’s going to happen next in these fast-moving cases. As Kyle Cheney noted in his Politico piece last week, “The Trump administration has asked appeals courts in the Texas-based 5th Circuit and the Missouri-based 8th Circuit for expedited rulings on the matter. But it has also asked appeals courts in other parts of the country to slow-walk their consideration.” And the class certification order in the Central District of California case can also be immediately appealed—at least with the permission of the Ninth Circuit.

One way or the other, it stands to reason that the legality of the Lyons memo will make its way to the Supreme Court sooner, rather than later. And when it does, it will necessarily be one of the most important immigration disputes to arise out of this administration’s efforts to date—not just because of the number of people who are directly affected by the policy (and how it affects them), but because of how fundamentally it attempts to rewrite a distinction that U.S. immigration law (and the Supreme Court’s own case law) has maintained since at least the 1950s: Between those stopped at the border, and those who, through whatever means, are living their lives on U.S. soil—to whom the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment unquestionably applies. To borrow a line from Adam Serwer, the cruelty may well be the point of the Lyons memo. But the law demands—and ought to demand—a heck of a lot more.

SCOTUS Trivia: The First Monday in … December?

This isn’t Supreme Court trivia, per se. But I’ve been spending a lot of time recently with old congressional records, and wanted to flag a quirk that’s in the text of the original Constitution and that says quite a lot about how the Founders originally envisioned the job of being a member of Congress. Specifically, as Article I, Section 4, Clause 2 of the Constitution provided, “The Congress shall assemble at least once in every Year, and such Meeting shall be on the first Monday in December, unless they shall by Law appoint a different Day.”

Thus, congressional sessions typically began on the first Monday in December, even for a Congress that entered into office that March—from the Founding all the way through the entrance into force of the Twentieth Amendment in 1933. Section 2 of that latter proviso specifies that “The Congress shall assemble at least once in every year, and such meeting shall begin at noon on the 3d day of January, unless they shall by law appoint a different day.” And although Congress has, at various points, appointed a different day for the beginning of the next session, the strong norm has been to follow the constitutional formulation (as amended) throughout our history.

Among other things, the First Monday in December Clause meant not only that Congress was often out of session for months even after newly being elected, but that the second session of each Congress typically post-dated the intervening elections—during which many of the members would often be “lame ducks.”

There’s broad consensus on why the Founders initially opted for December. As one historical note on the Senate’s website explains, “The 18th-century framers of the United States Constitution, accustomed to an agriculturally based economy with its cycles of planting, growing, and harvesting, considered the mostly dormant month of December to be a particularly good time for senators and representatives to begin their legislative sessions.” The Supreme Court, too, eventually followed the same pattern—with its term beginning on the first Monday in January as of 1827; and the first Monday in December as of 1844 (where it remained until 1873). In other words, the First Monday in December used to mark the beginning of the work year for official Washington—with the business at hand usually (albeit not always) wrapped up by the end of June, if not sooner. Even back then, it seems, no one wanted to spend their summers in the District of Columbia.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one. If you are, I hope, circumstances permitting, that you’ll consider upgrading:

Either way, this week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content no later than next Monday (and something tells me sooner). Have a great week, all!

In case you’re wondering why the class action is seeking only declaratory relief, rather than an injunction against the policy on a nationwide basis, there are statutory limits on the jurisdiction of federal district courts to issue class-wide injunctions in immigration detention cases that arguably don’t apply to class-wide declaratory relief.

"Of course, it’s hard to imagine any Congress, let alone the current one, making it easier for servicemembers to sue the federal government." True, but that fact only highlights the ease with which Congress allowed for huge damage claims (for senators and only for senators), retroactively, when the government lawfully subpoenas phone records. Prigs!

Thanks so much for this! I've been wondering the details of their legal justification so I can understand better who is at the greatest risk. (Not that immigrant of color isn't at risk in this lawless and cruel environment).