152. Non-Party Relief and Judicial Supremacy

Thursday's birthright citizenship oral argument hits at least somewhat different after and in light of Friday's Alien Enemies Act ruling—in which the Court ... provided relief to non-parties.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. I’m grateful to all of you for your continued support, and I hope that you’ll consider sharing some of what we’re doing with your networks.

As has been true every week since we launched in November 2022, each Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. We also just launched “First One,” the weekly bonus audio companion to the newsletter for paid subscribers, with the latest episode dropping last night. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit:

I already wrote a lengthy post about Friday’s ruling in “A.A.R.P. II”—in which a majority of the Court indefinitely blocked any further removals under the Alien Enemies Act of anyone detained in the Northern District of Texas. I thought I’d use today’s regular issue of the newsletter to do two things: to expand a bit on one of the points I made Friday—that the A.A.R.P. ruling paints Thursday’s oral argument in the birthright citizenship cases in a very different light; and to take a step back and say a bit more about the real stakes of all of these cases, i.e., when is the entire federal government “bound” to comply with a federal court ruling?

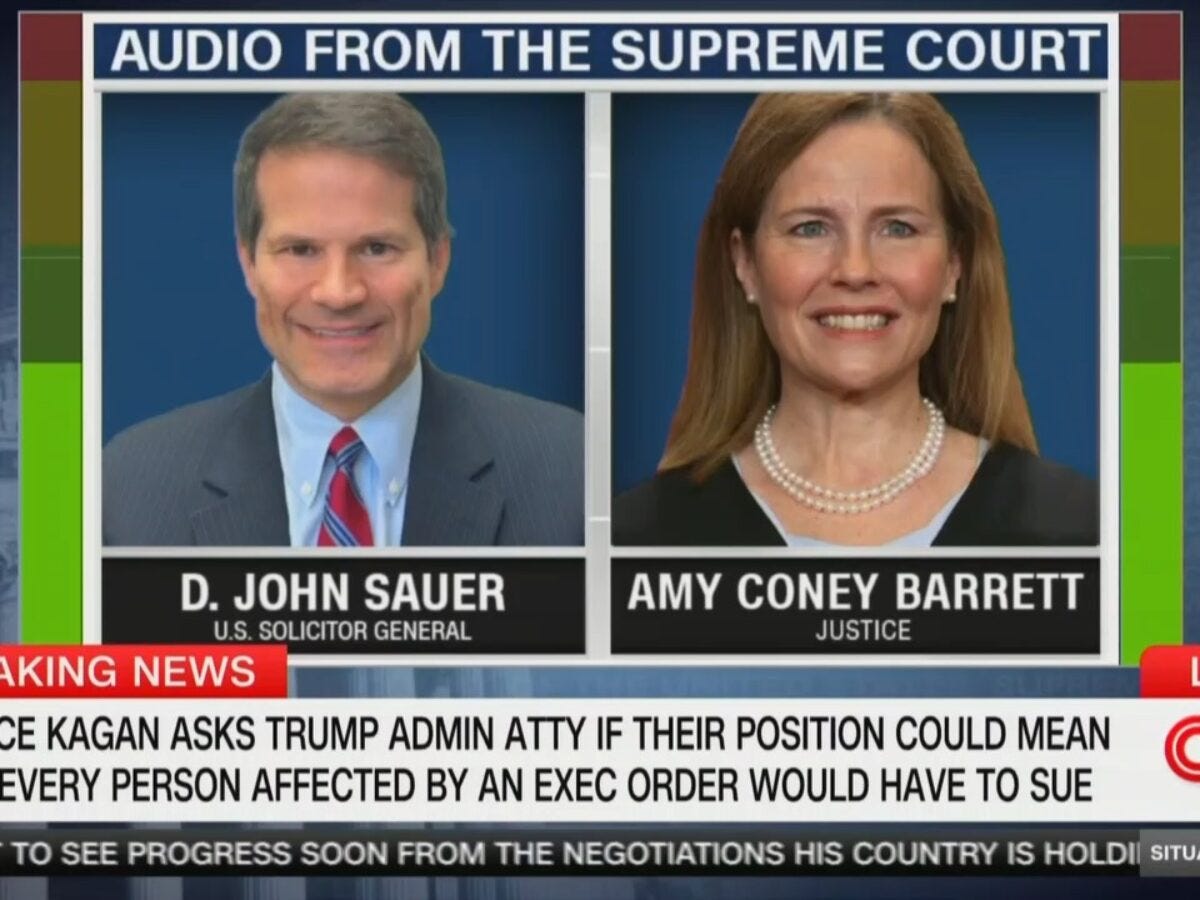

After a few attempts at hedging, Solicitor General Sauer eventually gave a remarkably direct answer when asked this question by Justice Barrett on Thursday. And as I explain below the fold, my own view is that his answer is correct—albeit in a way that heavily undercuts a key analytical piece of the government’s opposition to “nationwide” injunctions. Simply put, you can’t simultaneously accept what Justice Barrett called the “Cooper versus Aaron kind of situation” (more on that below) and argue that federal courts lack the power to provide relief that benefits non-parties. Ultimately, it’s one or the other. And the question A.A.R.P. II raises is whether the justices fully understand the implications of the choice that now confronts them.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

Besides Thursday’s argument and Friday’s ruling in A.A.R.P. II, there were only two other newsworthy events to come out of the Court last week. On Wednesday, and over no public dissents, the Court refused to block Florida’s impending execution of Glen Rogers. And on Thursday, the Court issued a single (unanimous) ruling in an argued case—with Justice Kagan’s opinion in Barnes v. Felix rejecting the “moment of threat” rule some lower courts, including the Fifth Circuit, had adopted with respect to when law enforcement officers are entitled to qualified immunity from excessive force claims. Instead, the Court reaffirmed that the question is whether, under the totality of circumstances (and not just at the moment the officer uses force) a reasonable officer would have known that his conduct was unlawfully excessive. The Court remanded that question to the Fifth Circuit—hence the unanimity. (Justice Kavanaugh wrote a separate concurrence, highlighting the challenges courts face in trying to conduct after-the-fact analysis of use-of-force claims when drivers pull away in the midst of a traffic stop.)

For those keeping score at home, the decision in Barnes continues the rough start to the term for the Fifth Circuit, which is already 0-3 in merits cases at the Supreme Court this term—with a whole bunch more still to come. (The Fifth Circuit was also summarily reversed in A.A.R.P. II, although that doesn’t count toward the totals for merits cases.)

Turning to this week, the only two things we expect for sure are an Order List at 9:30 ET this morning; and one or more opinions in argued cases Thursday starting at 10:00 ET. Even with Friday’s ruling in A.A.R.P. II, the justices are still sitting on a bevy of high-profile emergency applications—including the two immigration cases I wrote about last Thursday;1 the DOGE-access-to-Social-Security-data case; the Wilcox case (in which Chief Justice Roberts’s administrative stay has now been in place for 40 days); and yet another emergency application filed by the Trump administration on Friday, this one seeking both an “administrative” stay and a stay pending appeal of a district court ruling blocking a large number of the government’s attempted RIFs of existing employees. It’s impossible to predict which of these applications will produce rulings in which order. But it stands to reason that, at some point, the justices will have to clear out the backlog.

The One First “Long Read”:

The “Cooper Versus Aaron Kind of Situation”

There is a heck of a lot to say about Thursday’s oral argument in the birthright citizenship cases (some of which I said in an op-ed in Saturday’s New York Times). For now, though, I want to focus on a specific exchange between Solicitor General Sauer and Justice Barrett—both to explain, in English, what Barrett was asking; and to unpack the rather remarkable consequences of what Sauer eventually answered.

The exchange started with Barrett trying to reconcile answers Sauer had previously given to questions from Justices Kagan and Kavanaugh. To the former, he had suggested that the government might not follow a circuit-level precedent in a different case, even within the same circuit. To the latter, he had suggested that, once the Supreme Court had resolved the merits of a legal question (like the validity of President Trump’s executive order purporting to restrict birthright citizenship), the government would abide by that ruling. Pushed to reconcile the seeming disparity between those views, Sauer responded that it’s the longstanding practice of the Department of Justice to “generally” respect intra-circuit precedent.2 But he confirmed, twice, that the government would follow any Supreme Court ruling on the merits. As Justice Barrett summed it up, “you accept a Cooper versus Aaron kind of situation for the Supreme Court but not for, say, the Second Circuit.”

This exchange got a lot of play in the media after the argument—mostly for Sauer not agreeing that the government would always be bound by circuit precedent within that circuit. But I actually think Sauer’s response is analytically (and historically) correct. It’s just that it ought to have some rather unintended consequences in the very cases in which he gave it.

Who is “Bound” by the Supreme Court?

Back in August 2023, I devoted a bonus issue of the newsletter to the question of what it means to be “bound” by a Supreme Court decision. As I explained in some detail there, when the Supreme Court decides a case, its judgment only formally binds the parties and lower courts in that specific case. Any majority opinion only “binds” lower courts in other cases because it presumably reflects how the justices will rule on an appeal if those courts rule to the contrary. And it only “binds” government officers because officers who act in a manner contrary to the Supreme Court’s opinion will likely (1) be sued; and (2) lose. We may use the word “bound” to describe each of these latter scenarios, but we’re actually (if not obviously) using different definitions of the verb than what we mean when we refer to those who are formally bound by the Court’s mandates.

The “Cooper versus Aaron situation” to which Justice Barrett was alluding is the ongoing debate over the Supreme Court’s monumental but analytically … unsatisfying August 1958 ruling in Cooper v. Aaron, in which the Court held that Little Rock school board officials were themselves bound to desegregate Little Rock’s public schools by the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. As my earlier post explained, Cooper may reach the right result, but the crucial analytical moves it makes to support that result are a combination of overstated and incomplete. What Cooper really stands for is what Sauer conceded at Thursday’s argument—that practically, albeit not formally, once the Supreme Court has ruled on a legal question, the federal government understands that ruling to have conclusively settled the matter, at least in the near term. That does, indeed, follow from Cooper. And I think it has to be correct, albeit for the prosaic reasons I suggested in my earlier post—not the analytically implausible ones provided by the Cooper Court.

But whereas a number of accounts of Thursday’s argument seized on Sauer’s hedging with respect to following circuit precedent, the far bigger story to me is his lack of hedging on Cooper v. Aaron. For some astute Court-watchers, the upshot of that exchange was Sauer conceding that the Trump administration will necessarily follow whatever the Supreme Court says in this (and other) cases. I certainly hope that that’s true. For now, I think the implications are smaller—and, in the short term, perhaps more significant.

A.A.R.P. II and the Implications of Sauer’s Concession

Recall that the whole debate in the birthright citizenship cases, at least in the posture in which they reached the Supreme Court, is over whether federal courts have the power to issue relief that directly benefits non-parties. The principal legal (as opposed to practical) objection to “nationwide” injunctions is that they violate Article III because federal courts lack such power. Indeed, the government’s applications in the birthright citizenship cases devote significant attention to this claim.

But Sauer’s (in my view, correct) concession that the government must necessarily follow the Supreme Court’s legal interpretations—its opinions, and not just its judgments—seems to concede that there are circumstances in which non-parties permissibly benefit from federal court rulings, i.e., everyone who benefits from a Supreme Court decision the reasoning of which calls into question a state law, federal statute, or executive order. Even Sauer seems to be agreeing that, were the Supreme Court, in a case brought by a single, proper plaintiff, to hold that Trump’s birthright citizenship executive order is invalid, that ruling would redound to the immediate benefit of … everyone—without running afoul of Article III. If the government, in response to such a ruling, stops applying the executive order to anyone, then the ruling has the same effect as a nationwide injunction. This reasoning crystallizes a point I’ve tried to make before: The fight over nationwide injunctions is entirely (and only) over what happens until the Supreme Court has conclusively reached the merits—whether federal courts can issue interim rulings that also benefit non-parties. Even the government, at least as of Thursday, concedes that once the Court has spoken, that’s that.

But consider, in this respect, what happened the very next day in A.A.R.P. II. There, 27.5 hours after the end of oral arguments in the birthright citizenship cases, the Supreme Court itself directly granted relief to non-parties—barring the government from using the Alien Enemies Act to remove from the Northern District of Texas not just the two named plaintiffs, but the “putative class members,” i.e., every immigration detainee who has been, is being, or will be held in the Northern District of Texas, and is (allegedly) subject to President Trump’s March 15 Alien Enemies Act proclamation. It’s true that, once a class is certified, even absent class members (those folks who are part of the class but are not the named plaintiffs) are typically treated as “parties” for purposes of federal procedural rules. But that is not typically true prior to certification.

There are certainly good arguments for why courts should nevertheless be allowed to recognize putative classes for purposes of providing preliminary relief; the key here is that the Supreme Court accepted those arguments in A.A.R.P. II (over Justice Alito’s bitter dissent). Thus, not only has the Supreme Court now reaffirmed its power to provide direct relief to non-parties, but, pace Sauer, the government is now “bound” to respect at least that specific reasoning.

What Does All of this Mean?

I don’t mean to overstate things; the above analysis doesn’t mean the government must lose in the birthright citizenship cases. At most, it just means that, if the government prevails, it almost certainly won’t be because of a holding that Article III itself bars federal courts from issuing relief that benefits non-parties—since the Supreme Court regularly does it in general and just did it with remarkable specificity. (The government could win on the narrower ground that, although nationwide injunctions are consistent with Article III, they require additional showings that haven’t been made here—although Thursday’s argument spent surprisingly little time on what that additional showing ought to be.)

Rather, it seems like there are at least two important conclusions that emerge from reading Friday’s ruling and Thursday’s argument together as I’ve tried to above:

First, if Article III permits relief benefitting non-parties, then what we’re really fighting over is the Pareto-optimal way to protect non-parties (while not unduly burdening the government) during the time that it takes for a case to get from filing to the Supreme Court. I can understand why the justices might be drawn to provisional certifications of putative classes (as in A.A.R.P. II), but (1) that approach has downsides all its own; and (2) if this really is the fight, it might lead one to wonder why all this fuss over getting rid of nationwide injunctions in the first place—especially if there’s a way in which federal courts can provide much the same temporary relief in many (if not most) cases.

Second, any world in which the Court does anything to make it harder for plaintiffs to obtain effective, nationwide relief in that critical time period (between filing and Supreme Court review) is going to put much more pressure on the justices to reach the merits in these cases much faster. This came up repeatedly at Thursday’s argument (with the two advocates arguing against the stays urging the justices to reach the merits as soon as possible); and Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence in A.A.R.P. II suggests he lost an internal effort to have the Court immediately take up the two biggest, class-wide AEA questions: whether Trump’s invocation of the 1798 statute against Tren de Aragua is valid on its face; and the form and timing of the notice detainees must receive before they can be removed under the act.

Last December, I published a lengthy law review article pushing back against the Court’s mantra that it is “a court of review, not first view.” Specifically, I documented the sharp increase in recent years in the number of cases (and contexts) in which the justices have reached the merits of disputes in preliminary, if not premature, procedural postures. The article wasn’t critical of the practice per se, but it went to some lengths to document the many both visible and hidden costs that such behavior creates—especially at the scale we’ve recently seen. And even that pales in comparison to what it would mean if the Court started looking for ways to expedite plenary review in even some of the Trump-related cases, let alone most or all of them.

This, then, is the trap the Court has set for itself in the birthright citizenship cases: Any decision making it harder for lower courts to issue preliminary relief that is effectively nationwide will necessarily (and, perhaps, dramatically) ratchet up the pressure on the justices to intervene themselves at ever-earlier stages of these cases—interventions that may be justified on a case-by-case basis, but that will produce mounting, if not increasingly unsustainable, costs over time.

In contrast, leaving in place mechanisms to comprehensively freeze the status quo (as the Court itself did in A.A.R.P. II) buys the justices time to let the merits play out first in the lower courts (hence the remand to the Fifth Circuit in A.A.R.P. II), and have the matter come back to the Court without the urgency of an emergency application or a hyper-expedited plenary appeal.

Whatever the justices decide, the one point that is hopefully clear is that there’s a third door here—the worst of both worlds, in which the Court both kneecaps the ability of lower courts to provide meaningfully universal interim relief and does nothing to allow itself to reach the merits at earlier stages of these disputes. I have my own views about which of the first two options would be better for the Court and the country; what can’t be denied is that the third would be a stunning abdication of judicial power at the moment in American history in which it is arguably needed the most.

SCOTUS Trivia: Cooper’s Uniqueness

Just because Cooper v. Aaron is on the brain, it’s a good chance to remind folks of the two points of trivia for which it is currently the clubhouse leader. First, and most significantly, it remains the only majority opinion in the Court’s history that was signed by all nine justices. It wasn’t just unanimous; it was issued in all of their names.

Second, and far more trivially, Cooper, decided almost 67 years ago, remains the most recent case in which the full Court held an oral argument in the month of August—there, the argument on the emergency application that helped precipitate the Court’s plenary review a few weeks later. As I noted in the trivia to a prior issue, the Court has held at least one argument in every calendar month more recently than the last time it sat in August.

Of course, the way things are going this year (and with this President)…

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone (no later than) next Monday.

Until then, I hope you have a great week!

One note on the application in the Venezuelan TPS case: The government received a rather … indecorous … amicus brief in support of its application from America’s Future, Citizens United, and the Conservative Legal Defense and Education Fund, much of which was devoted to casting a series of aspersions on the district judge who had issued the injunction at issue—including that he had manipulated the “related case” rules in order to preside over this one. Counsel for the amici has since filed a letter explaining that, in fact, the case was randomly assigned to Judge Chen. Sigh.

For a good summary of the practice, and of the history of (and reasons for) what the Department of Justice calls “intracircuit nonacquiescence,” see this 2010 OLC memo by now-First Circuit Judge David Barron.

Given your argument that Article III itself doesn’t prevent universal injunctions, do you think we might see some very narrow ruling in these cases? I’ve been thinking that even if universal injunctions should be rare, there are various ways they could be applied to the birthright citizenship cases without reaching a decision on universal injunctions more generally - for example, where the lower court is just saying that SCOTUS already decided this issue (i.e. in Wong Kim Ark) and allowing the government’s conduct would enable a constitutional violation, that seems like the strongest possible case for a universal injunction, and one that wouldn’t have applied to, say, Kacsmaryk’s mifepristone ruling. Or am I missing something here?

Thank you so much for your time and effort. Really helps to understand the SC actions by me, a non lawyer