13. Bruen's Increasingly Troubling Aftermath

Everyone agrees that the Supreme Court upended Second Amendment jurisprudence last June. Just how far the majority's new approach goes is something the Justices will soon need to clarify.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

As expected, it was a very quiet week at the Supreme Court, as the Justices continued their un-official mid-winter recess. The Court issued only two orders—one refusing to stay Texas’s execution of Wesley Ruiz (furthering a trend I covered a few weeks back); and one clarifying the briefing schedule in two consolidated cases the Court will hear later this Term. We don’t expect anything more from the Justices until at least their next regular Conference, set for Friday, February 17 (the next Order List is due at 9:30 ET on Tuesday, February 21). The Court also released the argument calendars for its March 2023 and April 2023 sessions, which don’t have quite the same critical mass of blockbusters as the earlier sessions from this Term.

There were two Court-related news stories that caught my attention: Ariane DeVogue had a fascinating behind-the-scenes piece for CNN on some of the security lapses that were uncovered during the Court’s investigation into the Dobbs leak, but not disclosed as part of its report. And Steve Eder had a piece for the New York Times about ethical questions surrounding the legal recruiting efforts of Jane Roberts (who, among other things, is married to Chief Justice Roberts). I’ll confess that, like my better half, I think that this story is much ado about very little. But it does underscore, once again, the broader lack of concrete and enforceable ethics rules and standards governing the conduct of the Justices and their immediate family members, which has problematic implications in cases that are far more troubling than this one.

I also had an op-ed in yesterday’s Times about the increasing exploitation of “judge shopping” (where litigants, by filing challenges to federal policies in “single-judge divisions,” can effectively hand-pick the specific judge who hears their case and who can block the policy on a nationwide basis). Among other things, this uptick may have something to do with the topic of an earlier issue—how the Court is increasingly deciding important legal questions at much earlier stages of disputes than has historically been the norm.

The One First Long Read: The Future(?) of Gun Regulation

I was still mulling over what to write about for this week’s feature when, Thursday afternoon, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (covering Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas) handed down a decision that, at least outwardly, seems totally preposterous. In United States v. Rahimi, a unanimous three-judge panel (Jones, Ho, and Wilson, JJ.)1 held that a federal statute that makes it a crime to possess a firearm while under an active domestic violence-related restraining order violates the Second Amendment. Yes, you read that right: an individual who a court has already found poses an ongoing threat of harm to a domestic partner has a constitutional right to possess firearms up to the moment he violates the restraining order (at which point the violation of the restraining order is usually a … secondary … concern).2

The panel defended this analysis (in which Judge Ho was “pleased to concur”) as being compelled by the Supreme Court’s decision last June in New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n v. Bruen. As I suggest in what follows, I don’t think that the panel’s reading of Bruen is necessarily wrong. But insofar as that’s true, it thereby reveals two problems with Bruen itself, both of which the Justices ought to consider at least clarifying (if not fixing) sooner rather than later.

Before turning to the Fifth Circuit’s analysis, let’s start with the underlying statute, 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8):

The statutory subsection is worth reading in full. But in a nutshell, there’s no due process issue here; an individual can violate this statute if and only if they knowingly violate a court order of which they are aware.

As for why this fails constitutional muster, the answer, per the Fifth Circuit, is the absence of any sufficiently on-point historical analogues. This was the key move that the six-Justice majority made in Bruen: In the 14 years since a 5-4 majority first held that the Second Amendment protects a right to private self-defense in District of Columbia v. Heller, courts had generally followed a two-part means-end analysis—analyzing whether a specific gun regulation burdened core Second Amendment conduct, and, if so, demanding an especially persuasive justification for imposing such a burden. (This 2019 Congressional Research Service report nicely summarizes the post-Heller jurisprudence.)

Bruen completely scrapped that framework in favor of a test focused on “history and tradition,” i.e., whether contemporary laws infringing upon the rights of gunowners have precedents from the relevant time period, although whether that time period is 1791, when the Second Amendment was ratified, or 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment—which putatively applied the Second Amendment to state and local governments—was ratified is itself the subject of a significant and vital debate that Bruen … doesn’t resolve.

Thus, after Bruen, the burden falls entirely on the government to find historical analogies for contemporary gun restrictions—and to persuade contemporary courts that the proffered analogies are fitting. Thus, in Rahimi, the federal government argued with more than a little force that § 922(g)(8) could be analogized to Founding-era laws that disarmed entire classes of people considered to be dangerous (kind of like those subject to DV-related restraining orders). Nevertheless, the panel found that analogy insufficiently compelling:

In other words, the reason why § 922(g)(8) doesn’t have a Founding-era analogy is because it is too finely tailored in comparison to older laws that swept more broadly, by requiring both case-specific findings about the restrained individual and about the person to whom they pose a danger. Of course, without such tailoring, § 922(g)(8) would likely violate the Due Process Clause, but that’s no never mind to the panel.

Critically, although others may disagree, I don’t think that the Fifth Circuit’s decision is an obviously incorrect reading of Justice Thomas’s majority opinion. Or, if it is, it’s one that has been repeated by a bunch of federal courts over the last seven months. After all, this kind of “analogy hunting” has led courts to strike down an array of gun restrictions in decisions that seem to defy common sense, like the one striking down the federal statute that makes it a crime to destroy or otherwise mutilate a gun’s serial number because serial numbers were unknown to the Founders. Here’s the key passage from Bruen itself:

In that respect, Rahimi exposes two different problems with Bruen: The first problem is that its command to courts to measure contemporary gun regulations by the yardstick of “historical analogues” yields a profoundly subjective test that will lead principled judges acting reasonably to reach diametrically opposed conclusions about the same laws. As Rahimi makes clear, whether a historical example is sufficiently “analogous” will almost always be in the eye of the beholder.

After all, if “dangerousness” laws aren’t a sufficient analogy for § 922(g)(8), which exists entirely because of the danger those subject to DV-related restraining orders pose to their intimate partner, what could be other than a DV-specific restriction from 1791 (or 1868)? To illustrate the point, there have been, according to Professor Jake Charles, seven district court decisions since Bruen about § 922(n), which bars those under felony indictment from new gun acquisitions. Those seven courts have divided 4-3, largely by disagreeing about the relevance of the claimed historical analogies.

The second problem is that, even if it were possible to articulate a more objective way of identifying historical analogues, this is just no way to ask courts to interpret the Constitution. American society in 1791, and even in 1868, did not recognize domestic violence as the standalone moral and legal scourge that we understand it to be today (the Nineteenth Amendment, guaranteeing women the right to vote, was not ratified until 1920). It would be one thing if there were compelling evidence that those who drafted the Second Amendment in 1791, or those who drafted the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, intended to extend its protections to encompass any and all conduct that was not specifically prohibited at that time. But as Charles (and others) have explained, Bruen doesn’t hold up as an exercise in any recognizable form of “originalism” as an interpretive methodology, even for those who generally adhere to that approach.

I confess to having somewhat idiosyncratic views about the Second Amendment—views that derive in part from my academic work on the Founding-era militia, and just how much importance the Constitution (and early Congresses) placed on able-bodied (white) men to serve as the law enforcement force of last resort in a true domestic emergency; but also in part from my disagreement with Supreme Court cases that have rejected a constitutional right to government protection. Indeed, although there is a lot about Justice Scalia’s decision in Heller that I find deeply problematic, I’m not sure at the end of the day that the Court reached the wrong result.

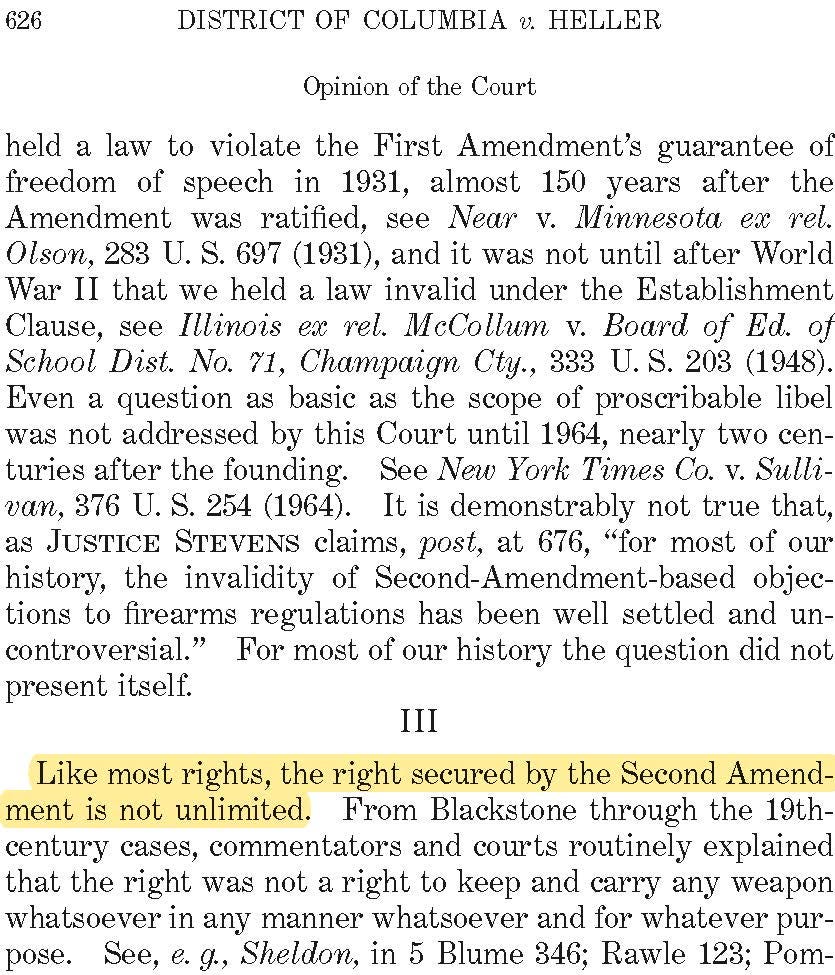

But even Justice Scalia understood that, like every other right in the Constitution, the Second Amendment is not absolute. Here’s his majority opinion in Heller:

And the measure of when Second Amendment rights can be infringed ought not to depend upon the persuasiveness to individual judges of forced (and inevitably flawed) analogies to a time in American history in which people lived radically different lives—and in which, among other things, white men held a monopoly over government offices; and the technology was such that a single individual would have been hard-pressed to use a firearm to kill dozens of others in a single shooting. This may help to explain Justice Kavanaugh’s separate concurring opinion in Bruen, which Chief Justice Roberts joined, which tried to articulate limits to the majority’s analysis. But at least thus far, those limits have proven … elusive.

Simply put, the more that lower courts read Bruen to yield a practical absolutism to the Second Amendment by resisting what sure appear to be apt analogies, the more it is incumbent upon the Supreme Court to either confirm that that’s what the six-Justice majority intended, or to clarify that, to the contrary, governments may reasonably regulate firearms in contexts in which they have especially persuasive justifications for doing so, even if no similar justifications existed at some random prior point in American history.

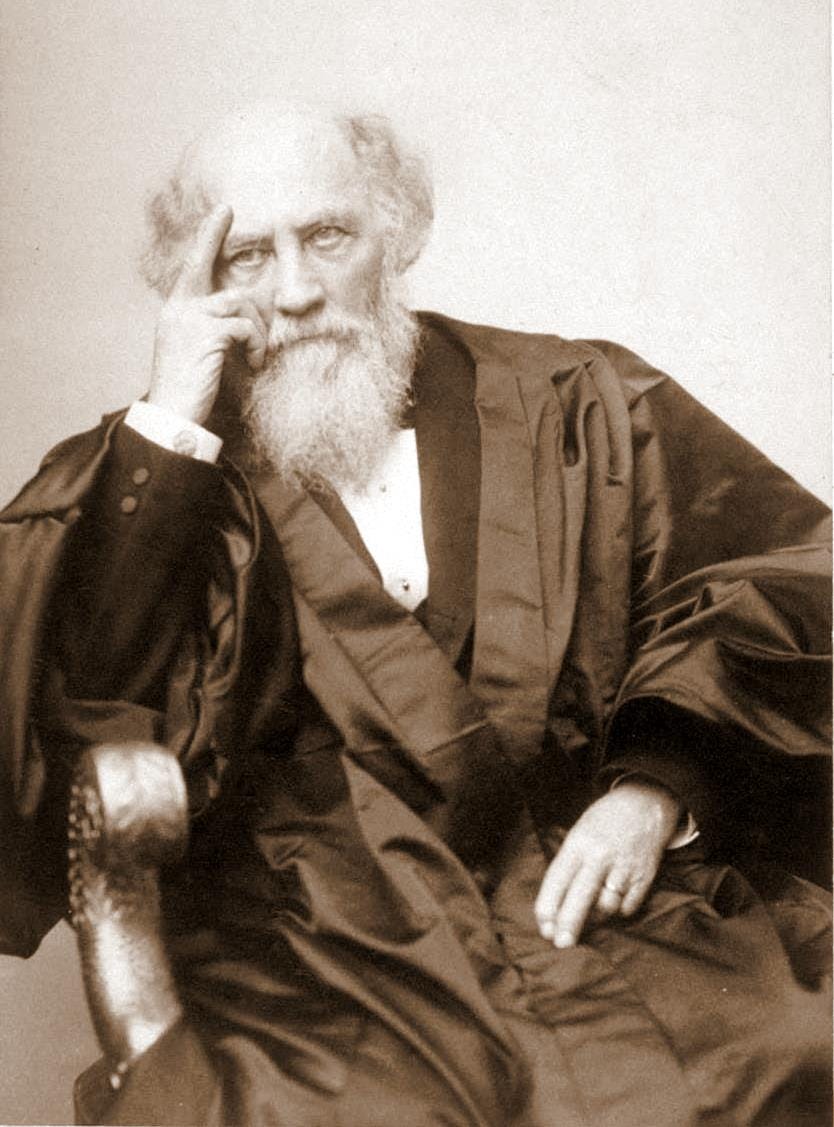

SCOTUS Trivia: Justice Field’s Robes

I already mentioned this piece of trivia in an earlier bonus issue, but it seemed apropos here: As Garrett Epps noted in a February 2016 essay in The Atlantic, there’s probably only one Justice in the Court’s history “to wear a coat specially tailored so that he could fire pistols through both pockets at once.” Indeed, given the background, it’s probably not beyond the realm of plausibility that, at least while he was riding circuit, Justice Stephen Field was armed while sitting on the bench. And those who crossed Field did so at their peril.

The backstory to Field’s arming himself is equal parts preposterous and salacious. Here’s what I wrote about it back in November:

While “riding circuit” (sitting as a circuit judge) in California, Field had presided over a contentious case involving a claim by Sarah Hill, represented by her then-husband David Terry (who had once been Field’s colleague on the California Supreme Court), that Hill had previously been married to a silver baron, and was therefore entitled to a share of his estate. . . . On September 3, 1888, Field ruled against Hill (and Terry), and, although accounts differ on who started it [as between Hill, Terry, and Field himself], eventually held both of them in contempt (and sent them to jail) for causing a scene in the courtroom.

Terry vowed revenge. When Field returned to California in June 1889 to once again ride circuit, the Attorney General ordered the local U.S. Attorney to assign Field a bodyguard. The U.S. Attorney assigned David Neagle to accompany Field, in case Terry tried to make good on his threat. Sure enough, when Terry and Field ended up on the same overnight train from Los Angeles to San Francisco on August 14, matters came to a head. Terry tried to attack Field at a railroad stop in Lathrop. According to witnesses, Neagle raised his pistol and shouted “Stop! Stop! I am an officer!” When Terry reached into his pocket, Neagle killed him with two shots.

Field and Neagle were jailed on charges of murder (yes, this is the only time in American history that a sitting Supreme Court Justice has been arrested on felony charges). But although Field was quickly released (apparently via a writ of habeas corpus), Neagle’s case was harder. The issue Neagle’s petition raised was that Congress had never specifically authorized his appointment. So whether he was acting lawfully in defense of Field when he shot and killed Terry turned on whether the U.S. Attorney had the unilateral legal authority to deputize him—whether the Constitution gave the Executive Branch the power to protect key federal officers even if Congress hadn’t provided for it.

The Supreme Court eventually sided with Neagle, albeit over two dissents(!), in a case that, to this day, stands as an important precedent for the President’s power to act in some circumstances without express congressional authorization. But for present purposes, the focus of the story is Field. As Epps put it seven years ago, “They don’t make justices like the late Stephen J. Field any more.” That may not be a bad thing.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week—and I hope we get our power back in Austin sometime soon (this morning begins Day *6* for us without it).

In legal citations, the norm is to use “JJ.” to refer to a list of multiple judges (or Justices).

According to a 2003 study published in the American Journal of Public Health, the presence of a firearm in the home during a domestic violence incident increases the risk of death fivefold.

Can you say more about your disagreement with Castle Rock and similar decisions?

If Bruen relies on the state of things at the time of the founding, then it follows that 2A only protects the rights to carry single shot pistols or single shot muskets. What am I missing?