9. The Missing Court-Martial Docket

Forty years after Congress gave the Court the power to hear direct appeals from military convictions, the Justices are taking virtually no cases brought by servicemembers

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

As expected, last week was quiet at the Court, producing just a lone housekeeping order regarding an upcoming argument. We expect a regular Order List (out of last Friday’s Conference) later this morning at 9:30 ET, which could include new grants of certiorari (for cases to be argued later this year); and a bunch of denials of pending petitions, as well.

Then, at 10:00, the Court’s January argument session begins. The Court is hearing only seven cases over the next two weeks (despite having 10 argument slots), part of the broader trend of the shrinking merits docket. And although some of the cases are of potentially broad significance, the January session doesn’t have the same collection of blockbusters that we saw in the fall argument sittings (or that we’re expecting in February).

There’s also been no announcement from the Court that any opinions in argued cases are expected this week. That extends the unprecedented streak of not having a single opinion of the Court since the Term began back in October. As Dr. Adam Feldman notes, the Court has already set a record for the longest period without such a decision from the beginning of a Term, and that record is getting longer by the day. We can’t know for sure why this is happening, but it can’t help that every week brings with it new, divisive emergency applications (including a pending request to put back on hold a number of New York gun control laws that a federal district court had temporarily blocked on Second Amendment grounds, only to have its ruling stayed by the Second Circuit). Indeed, a ruling on the gun application is likely in the next couple of days (and may well be the focus of next week’s issue).

Texas has also scheduled an execution for 6 p.m. (CT) on Tuesday—for which an emergency application is already pending. Expect a ruling on that either later today or tomorrow.

The One First Long Read: The Court’s Stingy Approach to Courts-Martial

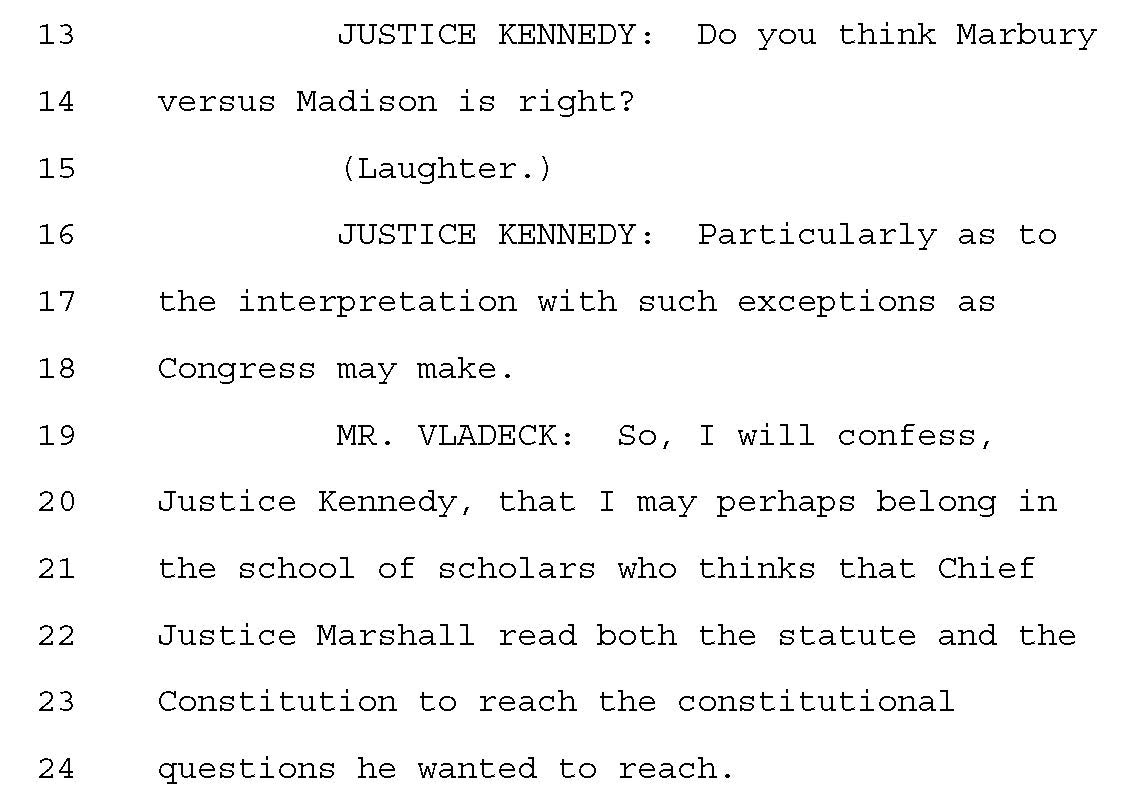

In thinking about what to cover this week, I was reminded that next week is the fifth anniversary of my first argument before the (or any) Court—in consolidated cases known initially as Dalmazzi v. United States, but in which the main ruling came in Ortiz v. United States. The argument was … an experience:

But Dalmazzi is a relevant foil here because it’s also the last time that the Justices granted a cert. petition from a servicemember (in that case, eight of them) in a direct appeal from a court-martial conviction. More than that, it is, as of today, the only such grant of certiorari since November 1996 (the Court has taken four other direct appeals from courts-martial since then, but all four were at the government’s request—and only two have come this century). The Justices’ reluctance to take up appeals from the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (CAAF) has become such an article of faith that there are miniature trophies—“Golden CAAFs”—awarded to the rare lawyer who succeeds in getting such a petition granted:

The paucity of grants is not reflective of an absence of cert.-worthy appeals. For instance, after CAAF in 2015 identified a conflict between two Supreme Court decisions—a 1996 case about the military death penalty and a 2002 decision involving Arizona’s—that only the Justices could resolve, the Court denied the resulting petition for certiorari without comment. The Court also refused to review a controversial 2016 CAAF decision about the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, even though former Solicitor General Paul Clement was lead counsel for the petitioner. In the last few years, the Justices have turned away a pair of petitions challenging whether retired servicemembers can constitutionally be subject to court-martial for post-retirement offenses (disclosure: I was counsel of record for the petitioners); and have refused to take up capital cases raising substantial statutory, constitutional, and jurisdictional questions. And there are plenty of other individual examples, along with broader critiques of CAAF and well-taken claims that it is not living up to its purpose as the military’s court of last resort.

Historically, this trend might not seem surprising. As late as World War II, courts-martial were ad hoc proceedings better understood as administrative impositions of discipline than as judicial proceedings. The only way civilian courts could review convictions by courts-martial was through habeas petitions brought by military prisoners. And even then, civilian courts could only decide if the court-martial had subject-matter jurisdiction over the offense and/or the offender; no non-jurisdictional errors could be corrected. (The Court broadened the standard of review in military habeas cases in 1953, but only to those claims that did not receive “full and fair consideration” in the military.)

It was only with the enactment of the Uniform Code of Military Justice in 1950 that Congress first created a court-like system for permitting (and resolving) direct appeals of court-martial judgments, with intermediate service-branch specific Courts of Criminal Appeals and then CAAF—the “supreme court of the military.”1 But these reforms, which have often been viewed as helping to promote the “civilianization of military justice,” had a massive effect on the procedural and substantive regularity and fairness of courts-martial. Almost overnight, courts began applying constitutional criminal procedure protections to courts-martial, and the “rough form of justice” decried by Justice Black in a 1955 decision started looking more and more like a recognizable criminal court system.

The one remaining aberration was the unavailability of direct review by the Supreme Court. Finally, in 1983, Congress agreed to (partially) close the gap. The Military Justice Act of 1983 gave the Supreme Court the power to review CAAF’s decisions via certiorari, treating it (with one major and deeply problematic exception) as if it were a state court of last resort.2 (One of the conclusions that the Court reached in Ortiz in 2018 was that the 1983 statute was constitutional in authorizing such appellate review.)

But if one of the primary goals of the 1983 statute was to encourage the Supreme Court to review CAAF as if it were a state court of last resort, that hasn’t ever materialized. In four decades, the Court has granted a total of 11 cases from CAAF, and seven of the 11 involved questions about either the subject-matter jurisdiction of the military courts or Appointments Clause issues arising from how military judges are selected (or, as in Dalmazzi/Ortiz, both). In other words, the Court is taking up substantive criminal law or criminal procedure issues from CAAF at a once-a-decade clip.

Given the bevy of worthy cases in which the Court is denying review, it would be one thing if the reluctance to take direct appeals from CAAF was in deference to collateral review via habeas corpus in the lower (civilian) federal courts. But again, that review extends only to issues that did not receive “full and fair consideration” in the military. And that standard is a remarkably deferential one—even more deferential than the incredibly broad deference that state convictions now receive in federal habeas cases. Here’s how the Tenth Circuit (which, because Fort Leavenworth is in Kansas, gets the lion’s share of military habeas cases) has framed it:

When an issue is briefed and argued before a military board of review, we have held that the military tribunal has given the claim fair consideration, even though its opinion summarily disposed of the issue with the mere statement that it did not consider the issue meritorious or requiring discussion. (emphasis mine)

In other words, even unexplained egregious errors by military courts that end up depriving servicemembers of their statutory or constitutional rights can’t usually be remedied on collateral review; it’s direct appeal or bust. (One of my favorite opinions by Justice Frankfurter is a dissent from the denial of rehearing in the 1953 case in which the Court articulated the “full and fair consideration” standard, where he explained all of the problems with it.)

Servicemembers are thus uniquely disadvantaged among all criminal defendants in the United States. Their ability to directly appeal a conviction to the Supreme Court turns, in almost every case, on whether CAAF grants a discretionary appeal. Whether CAAF does or not, they are uniquely unable to collaterally attack their convictions and sentences in civilian courts. And the Supreme Court has responded to these developments by … granting ever-fewer petitions from servicemembers. That reality is both inconsistent with the purpose of the 1983 statute and overly deferential to decisions by Article I civilian judges (as CAAF’s judges are required by statute to be) on questions of general federal constitutional or statutory interpretation.

There may soon be another case to test the Court’s lack of interest in military justice issues: In 2020, a 6-3 majority held in Ramos v. Louisiana that the right to a unanimous conviction protected by the Sixth Amendment is a “fundamental right” that also applies to the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. (Louisiana was the second-to-last state to allow non-unanimous convictions; Oregon was the last.) But the rationale of Justice Gorsuch’s majority opinion—that unanimity is an essential feature of impartiality—should also apply to courts-martial. Even though servicemembers don’t have a constitutional right to be tried by a jury, they have a statutory right to a jury-like “panel.” And CAAF has held that military defendants (“accused”) have (1) a Sixth Amendment right for the panel to be impartial; and (2) a due process right to an impartial factfinder.

During its current term, CAAF has agreed to take up six cases raising the question of whether non-unanimous court-martial convictions survive Ramos, and it heard argument in one of them, Anderson, on October 25. If (as seems likely) CAAF distinguishes Ramos and upholds the practice, it will be fascinating to see whether the Supreme Court is once again willing to leave such important questions to the military justice system—when, forty years ago, Congress unequivocally indicated a desire that it not do so.

SCOTUS Trivia: Justices Who Served

It seems only fitting to focus this week’s trivia on (some of) the Justices who served in the military before (or, in at least one case, during) their tenure on the Court.

According to the Curator of the Supreme Court (as relayed in a helpful summary by Kathy Shurtleff for the Supreme Court Historical Society), 40 of the Court’s 116 Justices served in the military at some point, although only one of the Court’s current members is on that list (Justice Alito, who joined the Army ROTC while at Princeton, and served in the Army Reserve from 1972–80). And Justice/Chief Justice Edward Douglass White was one of three Justices to serve in the Confederate Army (along with Justices L.Q.C. Lamar and Horace Lurton).

But whereas most of the 40 Justices who served had long since hung up their uniforms when they ascended the bench, the most glaring exception is Justice Frank Murphy. Murphy, who accepted FDR’s 1940 nomination to the Court only begrudgingly, spent most of World War II badgering the White House and the War Department for some type of military assignment (Murphy had served with distinction in the American Expeditionary Force during World War I). In the summer of 1942, he even persuaded General George Marshall to appoint him as a Lieutenant Colonel in inactive reserve status so that he could participate in training activities at Fort Benning, Georgia during the Supreme Court’s summer recess (Murphy would credit the time he spent in the Deep South during the war with drawing his attention to the systemic racism and civil rights deprivations faced by Black southerners).3

The problem that arose later during the summer of 1942 was the need for the adjourned Court to reassemble in a “Special Term” to decide whether a military commission could try eight Nazi saboteurs in Ex parte Quirin. Murphy was on “maneuvers” in North Carolina when Chief Justice Stone decided to convene the sensational hearing, and was summoned back to Washington through a “field telephone hanging on the side of a tree,” as Sidney Fine recounted in a 1966 article in the Journal of American History. But when Murphy showed up at the Court for the first day of argument wearing his Army uniform, it became apparent that his present military involvement precluded him from participating in an appeal (the record is … unclear … whether Murphy came to that realization on his own or had it made clear to him).

Suffice it to say, it’s not likely that the Murphy episode will repeat itself anytime soon.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, I hope you’ll consider sharing it:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue, which will be available only to paid subscribers (and will reflect upon the complexities of teaching the Federal Courts class given recent developments at the Court), will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

For convenience, I’m using the current names for these bodies. The service-branch courts of criminal appeals were originally “Boards of Military Review,” and CAAF was originally the “Court of Military Appeals,” yielding the rather amusing acronym, CoMA.

The exception involves cases in which CAAF has declined to grant a court-martial defendant’s discretionary appeal. In state courts, a criminal defendant can appeal to SCOTUS from an intermediate court if the supreme court denies discretionary review. In the military, though, the only way to get a case to SCOTUS is if (1) it’s a death penalty case; the government is the party that appealed to CAAF; or (3) CAAF exercises its discretion to grant a defendant’s permissive (non-capital) appeal. As Gene Fidell and I explained in a 2019 New York Times op-ed, this problematic loophole was deliberate (to reduce the docket pressure on SCOTUS), but is now anachronistic; in 1988, Congress eliminated most of the Court’s remaining mandatory jurisdiction—effectively cutting its docket in half.

An 1870 federal statute (the very one that was at issue in the 2018 Dalmazzi/Ortiz cases) bars individuals from simultaneously holding civil and military offices unless specifically authorized to do so by Congress. Murphy’s military assignment did not trigger that statute, though, because he was only a reserve officer on inactive status.

When I saw the "Golden CAAF," I was hoping that we oldtimers would get our military justice acronym pun due. So glad to have that hope paid off in the footnote shoutout to good ol' "CoMA." The prior name reinforces your excellent argument that the SCOTUS appeals from the military justice system need resuscitating. Call a Code Blue to remedy a Code Red.

Steve, your reference to " a controversial 2016 CAAF decision about the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, even though former Solicitor General Paul Clement was lead counsel for the petitioner.," appears to be referring to Sterling v. U.S., a USMC, case. "Controversy" I guess is in the eye of the beholder, but IMHO, it was anything but. I authored an Amicus Brief "In Support of Neither Party" objecting to certiorari as there were significant preservation and procedural issues permeating the case. Paul Clement--a brilliant appellate counsel--was boxed into a corner with respect to the RFRA issue, as the Petitioner had never made any requests for religious "accommodations" prior to her court-martial.