32. The Supreme Court and the Thirteenth Amendment

On Juneteenth, a brief look back at the 1883 ruling that gave the constitutional abolition of slavery a remarkably narrow compass

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

The Supreme Court last week handed down another five decisions in argued cases—leaving 18 to go with two weeks before the Court’s usual end-of-June deadline. Because of today’s federal holiday, the regular Order List from last week’s Conference is expected tomorrow at 9:30 ET, followed by decisions in one or more argued cases Thursday at 10:00 ET (and possibly, but not definitely, Friday as well).

As for the five merits rulings, the first three came down Thursday; the fourth and fifth on Friday:

Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians v. Coughlin: For seven Justices (with Justice Thomas concurring in the judgment), Justice Jackson held that, where a provision of federal bankruptcy law subjects various “governmental unit[s]” to suit (thereby abrogating those entities’ sovereign immunity), that statutory term includes Native American tribes. Justice Gorsuch dissented.

Haaland v. Brackeen: In a case that could have been one of the Term’s biggest, the Court largely sidestepped the most contentions issues in a challenge to the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act—a 1978 statute that gives various priorities to Native American families when it comes to adoptions of Native American children. For a 7-2 majority, Justice Barrett held that Congress had the constitutional authority under Article I to enact the statute; that the statute did not unconstitutionally “commandeer” state law; and that neither Texas nor the private plaintiffs had standing to challenge the statute on equal protection or non-delegation grounds. The equal protection issue, in particular (challenging the statute’s preference for Native American families), could have been a blockbuster—and may yet come back to the Court if a party with standing brings a similar challenge as part of a state-court adoption proceeding. For the moment, though, the Court dodged a potential constitutional landmine, with only Justices Thomas and Alito dissenting. (Justice Gorsuch’s separate concurrence is a remarkable read—and a compelling critique of the Supreme Court’s historically … skeptical … treatment of tribal sovereignty).

Smith v. United States: For a unanimous Court, Justice Alito held that, where a criminal defendant is convicted in a federal district court that is an improper venue, he can be retried in the correct venue (rather than having his re-trial barred by the Double Jeopardy Clause).

Lora v. United States: For a unanimous Court, Justice Jackson held that a provision of federal law that bars certain criminal sentences from being imposed concurrently (and thus requires the sentences to be imposed consecutively) applies only to a small and specific subset of crimes—not including the offense for which the defendant in Lora had been convicted.

United States ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, Inc.: For eight Justices, Justice Kagan held that, when a private party (a “qui tam relator”) brings a fraud claim on behalf of the federal government under the False Claims Act, the government may seek to dismiss the case after it intervenes regardless of whether it intervenes at the beginning of the case or later. Dissenting, Justice Thomas argued that, because he disagreed with the majority and would have held that the government cannot seek dismissal at any point, he believed that there are serious constitutional questions about whether the False Claims Act (and other statutes authorizing qui tam suits) violates Article II of the Constitution by giving private parties the ability to vindicate the “government’s” interests in certain civil suits. Given that Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett signaled their agreement about the gravity of the constitutional question (even while joining the majority opinion), it’s a good bet that this issue works its way back to the Court sometime soon.

The One First Long Read: The Civil Rights Cases and the Thirteenth Amendment

Juneteenth commemorates the anniversary of the order by Major General Gordon Granger proclaiming freedom for slaves in Texas on June 19, 1865—the last part of the United States in which emancipation became legally operative. By that point, the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, had already passed both the House and the Senate. It would be ratified on December 6, and proclaimed to be in force on December 18.

The text of the Thirteenth Amendment was designed to be sweeping. Section 1 provides that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” And, for the first time, a constitutional amendment expressly gave Congress the power to enforce the substantive provision, with section 2 providing that “Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

The Fourteenth Amendment (ratified in 1868) and the Fifteenth Amendment (ratified in 1870) would soon follow, but it was the Thirteenth Amendment—the first constitutional provision to directly regulate private conduct—that was supposed to be at the center of Reconstruction. And yet, as would be true for the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, the Thirteenth Amendment was soon interpreted by the Supreme Court more than a little modestly.

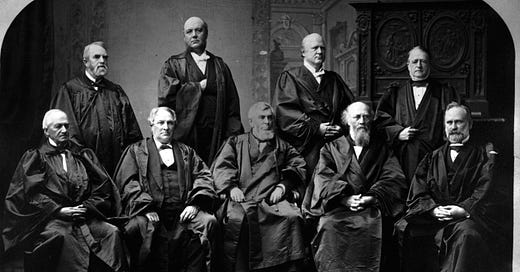

At issue in what’s known as The Civil Rights Cases was the Civil Rights Act of 1875—which banned discrimination based upon race in places of public accommodation, including “inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement.” By the time a series of constitutional challenges to the statute reached the Supreme Court in 1883, Reconstruction was over—unofficially by dint of the Compromise of 1877, but unquestionably in both Congress and the courts. Indeed, even though all nine Justices had been appointed by Republican Presidents, the Court had already signaled its hostility to broad readings of the Reconstruction amendments—in the Slaugherhouse Cases in 1873 and United States v. Cruikshank in 1876.

But Justice Joseph Bradley’s opinion for an 8-1 majority in The Civil Rights Cases went even further. The Civil Rights Cases is best known today for cementing the proposition that the Fourteenth Amendment only applies to “state action,” which does not include a state’s failure to enforce its own laws banning racial discrimination in places of public accommodation. Thus, racial discrimination by private actors can’t violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. Its holding that Congress couldn’t base the 1875 act on the Thirteenth Amendment was just as significant. In Bradley’s words:

The long existence of African slavery in this country gave us very distinct notions of what it was, and what were its necessary incidents. Compulsory service of the slave for the benefit of the master, restraint of his movements except by the master's will, disability to hold property, to make contracts, to have a standing in court, to be a witness against a white person, and such like burdens and incapacities were the inseparable incidents of the institution. Severer punishments for crimes were imposed on the slave than on free persons guilty of the same offenses. Congress, as we have seen, by the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, passed in view of the Thirteenth Amendment, before the Fourteenth was adopted, undertook to wipe out these burdens and disabilities, the necessary incidents of slavery, constituting its substance and visible from; and to secure to all citizens of every race and color, and without regard to previous servitude, those fundamental rights which are the essence of civil freedom, namely, the same right to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, and convey property, as is enjoyed by white citizens. Whether this legislation was fully authorized by the Thirteenth Amendment alone, without the support which it afterwards received from the Fourteenth Amendment, after the adoption of which it was re-enacted with some additions, it is not necessary to inquire. It is referred to for the purpose of showing that at that time (in 1866) Congress did not assume, under the authority given by the Thirteenth Amendment, to adjust what may be called the social rights of men and races in the community; but only to declare and vindicate those fundamental rights which appertain to the essence of citizenship, and the enjoyment or deprivation of which constitutes the essential distinction between freedom and slavery.

In other words, racial discrimination in places of public accommodation, however odious, was insufficiently connected to slavery (or to the “badges" of slavery) to be within Congress’s power to regulate under Section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment. As Bradley concluded, “When a man has emerged from slavery, and by the aid of beneficent legislation has shaken off the inseparable concomitants of that state, there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen, and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws, and when his rights as a citizen, or a man, are to be protected in the ordinary modes by which other men’s rights are protected.”

Only Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented. And although Harlan’s dissent 13 years later in Plessy v. Ferguson is perhaps better known, color me one who views his dissent in The Civil Rights Cases as some of his best work. On the scope of the Thirteenth Amendment, he fired back at Bradley:

The Thirteenth Amendment did something more than to prohibit slavery as an institution, resting upon distinctions of race, and upheld by positive law. My brethren admit that it established and decreed universal civil freedom throughout the United States. But did the freedom thus established involve nothing more than exemption from actual slavery? Was nothing more intended than to forbid one man from owning another as property? Was it the purpose of the nation simply to destroy the institution, and then remit the race, theretofore held in bondage, to the several states for such protection, in their civil rights, necessarily growing out of freedom, as those States, in their discretion, choose to provide? Were the States, against whose protest the institution was destroyed, to be left free, so far as national interference was concerned, to make or allow discriminations against that race, as such, in the enjoyment of those fundamental rights which by universal concession, that inhere in a state of freedom?

Thus, Harlan argued, “That there are burdens and disabilities which constitute badges of slavery and servitude, and that the power to enforce by appropriate legislation, the Thirteenth Amendment may be exerted by legislation of a direct and primary character, for the eradication, not simply of the institution, but of its badges and incidents, are propositions which ought to be deemed indisputable.” By refusing to allow Congress to regulate based upon that understanding, Harlan concluded, the Court was turning a blind eye toward the history that helped to precipitate the Thirteenth Amendment and the amendment itself—and opening the door to what would become the “Jim Crow” era in the South, with private businesses openly discriminating based upon race; state governments turning a blind eye; and federal courts powerless to provide any redress.

In that respect (and others), The Civil Rights Cases marked a turning point, not just for the Court, but for Congress. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 would be the last civil rights law Congress would enact for 82 years. And when Congress enacted a strikingly similar ban on racial discrimination in places of public accommodation as Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Supreme Court upheld it not by revisiting The Civil Rights Cases, but by relying upon the Commerce Clause—and data on which Congress had relied identifying the massive economic effects of racial discrimination in public accommodations, especially in the South. (Justice Douglas was alone in urging the Court to revisit The Civil Rights Cases.)

The Court finally embraced at least a somewhat broader reading of the Thirteenth Amendment in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., in which it relied upon Section 2 of the amendment to uphold the key provisions of the Fair Housing Act of 1968—which prohibit racial discrimination in certain private real-estate transactions. But Jones distinguished The Civil Rights Cases; it didn’t overrule the Court’s 1883 ruling. The net effect has been to push Congress to rely upon less well-tailored authorities, like the Commerce Clause, when it has sought to regulate and prohibit racial discrimination by non-governmental actors—reliance that has precipitated its own set of constitutional challenges, and that, if Harlan was right (and my own view is that he was), has prevented the Thirteenth Amendment from achieving anything close to its full constitutional purposes.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Constitution and Private Conduct

The Thirteenth Amendment stands out as one of only two constitutional provisions (and the first, chronologically) to directly regulate (and limit) private conduct. The other such provision is the Eighteenth Amendment, which inaugurated Prohibition (and was repealed by the Twenty-First Amendment). Because both provisions act not just against governments, but against people, they both specify that they apply within the United States, or any place “subject to their jurisdiction” / “the jurisdiction thereof.” This raises a raft of interesting (and still mostly unanswered) questions about the extraterritorial scope not just of these provisions, but of the rest of the Constitution.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

Today’s piece is very interesting, but leaves me wanting to know more about that time in our country. Seems to me the Court was very “activist” during those years.

Can anyone recommend good books about that period?

How Clarence Thomas and SCOTUS were beaten and reveresed by the new Democrat Arizona AG and Pima County DA. An innocent project finally got Barry Jones off death row for a crime he didn't commit.

But Republican AG Mark Brnovitch and Clarence Thomas said, "Innocence does not matter".

https://theintercept.com/2023/06/17/barry-jones-released-arizona-death-row/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=The%20Intercept%20Newsletter

An evidentiary hearing held by US District Court Judge Timothy Burgess, confirmed Barry Jones was innocent due to the Medical Examiners changing the time of death window from 24 to hrs. But Republican AG Mark Brnovich appealed to SCOTUS-

"During oral argument, the attorney general’s office said that it didn’t matter if the evidence showed Jones was not responsible for the crime that sent him to death row. “Innocence isn’t enough,” the state’s lawyer, Brunn Wall Roysden III, said. In May 2022, the justices agreed, reinstating Jones’s death sentence and destroying a lifeline for incarcerated people whose lawyers failed them at trial."

The new AZ AG stopped executions. Allowing Jones kegal team to do a deal to get released.

"On April 19, US District Judge Burgess approved the settlement agreement between Jones’s attorneys and the state. Two weeks later, Sandman filed a petition with the Pima County Superior Court requesting that Jones’s conviction be overturned. The state would agree to the request on the condition that Jones plead guilty to the agreed-upon charge. He would then be sentenced to 25 years with credit for time served."