31. Emergency Applications and the Merits

A common defense of the Supreme Court's aggressive granting of emergency relief is that the justices are just previewing the merits. Thursday's Alabama redistricting ruling was another counterexample.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

We’re entering the home stretch for decisions in cases that were argued during the Court’s October 2022 Term. In addition to handing down a regular Order List at 9:30 ET today, the justices are set to hand down some of the 23 remaining rulings from argued cases both Thursday and Friday at 10 ET. In other words, it could be a big week.

The Court handed down four decisions in argued cases last Thursday:

Health and Hospital Corporation of Marion Cty. v. Talevski: In the first of two surprising rulings to come down on Thursday, Justice Jackson, for a 7-2 majority, held that nursing home residents could sue a county-owned nursing home under 42 U.S.C. § 1983—for claims that the nursing home violated the Federal Nursing Home Reform Act. The ruling was surprising because (1) the Court has spent much of the past two decades making it harder for plaintiffs to enforce federal statutes in suits under § 1983; and (2) there was no circuit split on this issue, which made it unlikely that the Court was granting just to affirm the decision below (as it nevertheless did). But only Justices Thomas and Alito dissented from Justice Jackson’s majority opinion (Justices Gorsuch and Barrett each penned separate concurrences, but joined the majority in full). [N.B.: I helped to draft and file an amicus brief in this case in support of the plaintiffs on behalf of former HHS officials.]

Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC: For a unanimous Court, Justice Kagan sided with Jack Daniel’s in a trademark dispute against the maker of the “Bad Spaniels” squeaky chew toy for dogs. The majority opinion is a really fun read, but I’ll spare you the details here and encourage those who would like to know more to read it for themselves. (There are separate concurrences from Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justice Alito; and Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justices Thomas and Barrett—but all joined the majority opinion in full.)

Dubin v. United States: For an effectively unanimous Court (Justice Gorsuch concurred in the judgment), Justice Sotomayor held that the federal “aggravated identity theft” statute requires that a defendant’s use of another person’s means of identification be central to the offense, rather than merely ancillary to it (like the customer’s name on a credit card slip that includes a fraudulent charge). The Court thus reversed the Fifth Circuit, which had adopted the broader reading of the statute.

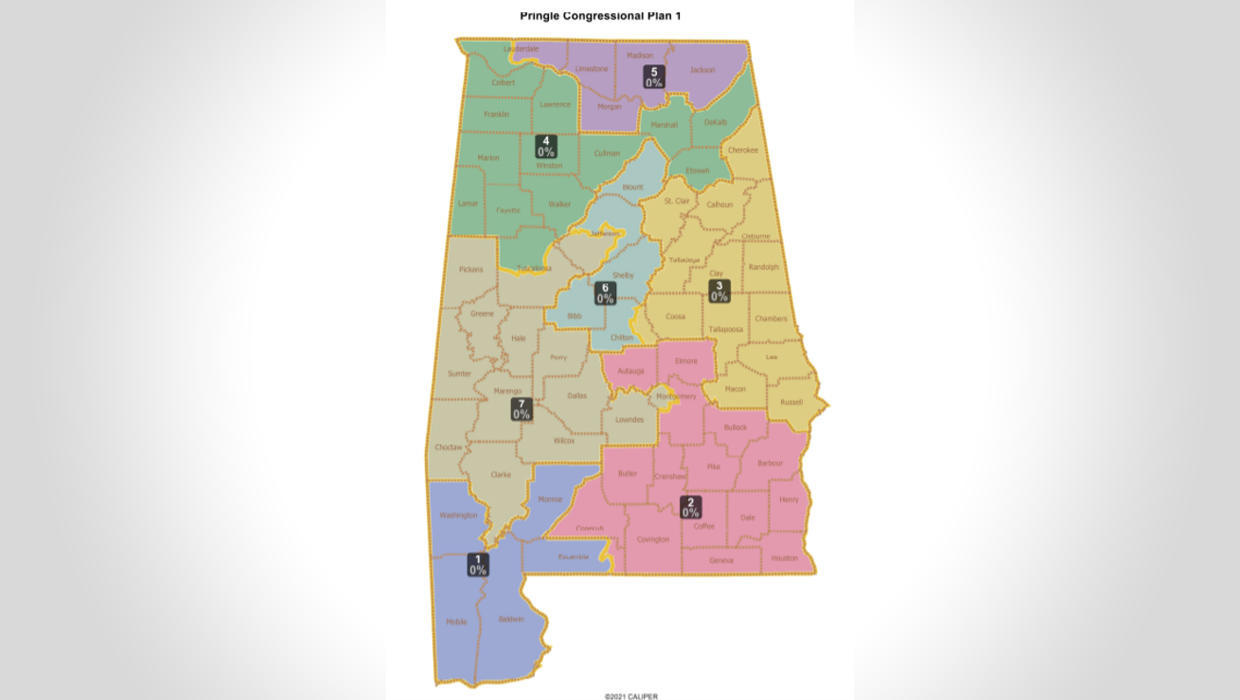

Allen v. Milligan: Finally, in what was, at least to this point, the most surprising outcome of the term, Chief Justice Roberts wrote for a 5-4 Court in affirming two district court rulings that had held that Alabama’s post-2020 Census congressional redistricting likely violates the Voting Rights Act. With Justice Kavanaugh and the three Democratic appointees joining him, Roberts reaffirmed—rather than narrowed—the Court’s 1986 ruling in Thornburg v. Gingles, and its interpretation of the Voting Rights Act to require states, in certain circumstances, to draw congressional districts specifically to provide opportunities to large and geographically compact minority groups. The ruling, which could have massive effects in ongoing challenges to the post-2020 redistricting in a number of states, was a surprise not only because of Chief Justice Roberts’ (and the other conservatives’) well-documented hostility to the Voting Rights Act, but because a 5-4 majority stayed those district court rulings (allowing Alabama to use its maps) in an unsigned, unexplained order last February. And that’s the prompt for this week’s long read.

The One First Long Read: The Merits of Emergency Orders

As the Supreme Court has come under increased criticism in recent years for the uptick in when and how it had granted applications for emergency relief (including from me), one of the common responses from the Court’s defenders is that, if the justices are confident that they are ultimately going to reverse a lower-court ruling when it reaches them for plenary review, then they ought to be able to get a head-start by freezing that ruling for however long the appellate process takes.

Even assuming the premise of this argument, it still runs into two serious problems. First, it effectively rewrites the relevant statutory authority to issue emergency relief by having a party’s entitlement to emergency relief rise and fall on just one of the four considerations that the Court has repeatedly held go into an application for a stay: the likelihood of success on the merits. And even if the Court is effectively eliminating the traditional balancing of the equities, including whether upsetting the status quo or preserving it would cause more harm (never mind the well-settled principle that the Court’s prior statutory interpretations require special justifications for rewriting), at the very least, it ought to say so.

Second, as we saw with a number of Trump-era cases, it’s increasingly true that, once the Court grants emergency relief at an early stage of the litigation, it ends up as the justices’ last word on the matter. Of the dozen-plus emergency applications involving Trump immigration policies, only one of those policies ever produced a merits ruling from the justices—Travel Ban 3.0. The others were discontinued before the Court could reach the merits, either before the end of the Trump administration, or after. The same pattern surfaced in non-Trump cases; when the Court blocked COVID mitigation policies in New York and California through emergency writs of injunction, the state and local governments tended to change the blocked policies—rather than continue to pursue what appeared to be a doomed appeal. In both of these respects, the “the Court is just previewing the merits” defense is more than a little unsatisfying.

But as the Alabama redistricting cases underscore, the premise itself is faulty. There are a meaningful (and growing) number of recent examples of cases in which the justices’ ruling at the emergency application stage did not presage their ruling on the merits. Here, as noted above, a 5-4 majority had voted last February to freeze the two district court injunctions at issue—and allow Alabama to use its contested congressional district maps for the 2022 midterm cycle—maps that included only a single minority “opportunity” district among Alabama’s seven seats, even though 27% of Alabamians (roughly two out of seven) are Black.

But in Thursday’s ruling, a different 5-4 majority (with Justice Kavanaugh the only justice in both majorities ) held that the district courts were correct—that the maps likely do violate section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by not creating a second minority opportunity district, and thus were appropriately subject to preliminary injunctive relief.

The net effect of this about-face is that Alabama was able to use congressional district maps in the 2022 midterm cycle that every court to review them held to violate the Voting Rights Act—and that produced a safe Republican seat as opposed to a seat that could well have been a safe Democratic seat. Ditto Louisiana and Georgia, and perhaps Ohio and South Carolina, as well. Indeed, as Melissa Murray and I suggested in the Washington Post on Thursday, it’s not a stretch to suggest that the Court’s unsigned, unexplained interventions in redistricting cases was directly responsible for Republican control of the House of Representatives. That’s problematic enough in the abstract; it’s even more troubling when, on plenary consideration, the Court walked away from those prior rulings.

The same thing happened last Term in Biden v. Texas—Texas’s challenge to the Biden administrations’ rescission of the Trump-era “Remain in Mexico” asylum program. After the rescission was subject to a nationwide injunction, the Biden administration sought emergency relief from the Supreme Court—making the same arguments that had regularly succeeded during the Trump administration, including that the President is entitled to deference when it comes to immigration policy and that nationwide injunctions are especially fraught. In August 2021, the Court denied the emergency application without explanation (over public dissents from the three Democratic appointees). But in June 2022, a 5-4 majority sided with the Biden administration and reversed the injunction.

To be sure, there’s one critical difference between these two cases: Because the standard for emergency relief is supposed to be higher than the merits, it is to be expected that there will be cases mirroring the Biden v. Texas scenario—a denial of emergency relief followed by a ruling for the applicant on the merits, where the justices are sympathetic on the merits but the equities don’t justify emergency intervention. But insofar as the Court is hewing to such a traditional understanding of emergency relief, that just further undermines the claim from its defenders that the Court’s rulings at the emergency application stage are just previews of the merits.

But the Alabama cases present the flip side: Where five justices thought Alabama met the high bar for emergency relief but not the lower bar for prevailing on the merits. The only justification provided at the time came in a concurrence by Justice Kavanaugh, which was joined by Justice Alito. For Kavanaugh, the problem was that the district court injunctions came “too close” to the election, and so ought to be frozen under the “Purcell” principle. But that argument was laughable then (the injunctions came in January when the election was 10 months away and the primary was four months away). And it looks even worse in hindsight. And although Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence included a cryptic footnote suggesting that a stay would have been justified even under traditional equitable analysis, he never explained why the harm to Black voters of allowing Alabama to use an unlawful congressional map was outstripped by the harm to Alabama of requiring it to redraw the map (even though that would’ve had to be the key for a justice who thought the maps were unlawful).

To make a long story short(er), Thursday’s ruling in the Alabama redistricting case reinforces the exact problem with the Court’s aggressive interventions in emergency applications in recent years: It undermines any argument that those interventions are just previews of the merits (clearly, they aren’t in at least many of these cases); it underscores how those interventions have allowed the justices to change what’s true on the ground without changing the underlying legal principles; all in a context that produced a direct (and ultimately unlawful) electoral advantage for Republicans at the expense of Democrats, up to and including control of the House of Representatives in the current Congress; and with no explanation from a majority of the Court for why this behavior is procedurally, substantively, or institutionally appropriate.

Other than that, though…

SCOTUS Trivia: Loving’s Anniversary

Today is the 56th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling in Loving v. Virginia, in which the Court struck down Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage, holding that it violated both the equal protection and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue, which will go behind the scenes on how at least some of the press corps covers the Court’s decision days, will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

Excellent opinion on the Alabama redistricting case. Tying emergency relief decisions to the political ramifications of same is an important point.