30. The "Rump" Court

From 1802–38, Congress forced a specific Justice to return to D.C. each August to resolve outstanding procedural matters—an obscure precedent that underscores Congress's powers over the Court's docket

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning (including holidays), I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it with your networks (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

The Court handed down three additional rulings in argued cases last Thursday:

Glacier Northwest, Inc. v. Teamsters: In what was easily the most broadly significant of Thursday’s three rulings, the Court held that a cement company’s state tort claims against striking workers for intentionally destroying the company’s property as part of a strike were not preempted by federal law, and so could proceed in state court. Justice Barrett wrote on behalf of a five-Justice majority (that included Justices Sotomayor and Kagan); Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch all concurred in the judgment (signaling, in different ways, that they would have gone even further); and Justice Jackson dissented. There’s a lot to say about the remarkably narrow ruling; what’s perhaps most interesting is that Sotomayor and Kagan were willing to sign onto Barrett’s opinion (and Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch were not). Could that be a harbinger of even bigger rulings coming down the pike in which there’s some effort on the part of the Democratic appointees to broker a compromise with some of the conservatives?

Slack Technologies, LLC v. Pirani: For a unanimous Court, Justice Gorsuch held that, under federal securities laws, a stock purchaser must show that his purchase can be traced to a false or misleading registration statement in order to hold the seller liable.

United States ex rel. Schutte v. Supervalu Inc.: For a unanimous Court, Justice Thomas held that a violation of the False Claims Act turns on whether the defendant actually knew that the claim he was submitting to the government was false—and not whether an objective person in the defendant’s position would know that it was false. Thus, a defendant who makes a good-faith mistake can’t be liable for “knowingly” making a “false” claim, but a defendant who acts in subjective bad faith can.

For those keeping score at home, that leaves no more than 27 decisions still to come from this Term’s argued cases, and that number could go down if the Court files a single opinion in either/both of the two remaining pairs of closely related disputes (affirmative action and student loans). We expect the next round of rulings this Thursday at 10 ET (after a regular Order List this morning at 9:30 ET).

The One First Long Read: The Antebellum “August” Term

In my research and writing about the Supreme Court’s “shadow docket,” one of my favorite historical footnotes comes from a brilliant 2006 article published in the Journal of Supreme Court History by Professor Ross Davies. Titled “The Other Supreme Court,” Davies’ essay looks at the strange-but-true existence of what he calls the “rump Court”—the one-Justice mini-term that Congress required the Court to hold every year from 1802 through 1838. As Davies reports, with two exceptions right at the end of that period, most of these sessions were “short and dull.” But they’re also a powerful reminder of just how much power Congress exercised over the Court’s docket in its infancy—going so far as to pick the specific Justice to resolve outstanding procedural issues for the better part of four decades, and empowering that single Justice to act in those matters on behalf of the full Court.

To quickly recap a whole lot of history (Davies’ article provides far more context), the “rump Court” was a technical outgrowth of the pitched battle between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans for control of the judiciary after the Election of 1800. In March 1802, Democratic-Republicans repealed the Judiciary Act of (February) 1801—also known as the “Midnight Judges Act,” in which the lame-duck Federalist Congress had attempted to create a bunch of new federal judgeships (and eliminate a seat on the Supreme Court) as part of their plan to entrench Federalist hegemony in the judiciary once the Federalists were out of power in the elected branches. Repealing the 1801 Act eliminated those new judgeships (a move that the Supreme Court effectively endorsed in Stuart v. Laird), and also restored the Court’s sixth seat (and the practice of circuit-riding, which the Federalist justices loathed).

One month after repealing the 1801 Judiciary Act, Congress enacted the Judiciary Act of 1802—which, most famously, eliminated the Supreme Court’s 1802 annual sitting by changing the beginning of the Court’s regular session from August to February, and doing so in April. The 1802 Act didn’t wholly eliminate the August sitting, however; it merely converted it into a single Justice’s disposition of procedural matters. Here’s the relevant text creating the new mini-session:

That it shall be the duty of the associate justice resident in the fourth circuit formed by this act, to attend at the city of Washington on the first Monday of August next, and on the first Monday of August each and every year thereafter, who shall have power to make all necessary orders touching any suit, action, appeal, writ of error, process, pleadings or proceedings, returned to the said court or depending therein, preparatory to the hearing, trial or decision of such action, suit, appeal, writ-of error, process, pleadings or proceedings: and that all writs and process may be returnable to the said court on the said first Monday in August, in the same manner as to the session of the said court, herein before directed to be holden on the first Monday in February, and may also bear teste on the said first Monday in August, as though a session of the said court was holden on that day, and it shall be the duty of the clerk of the supreme court to attend the said justice on the said first Monday of August, in each and every year, who shall make due entry of all such matters and things as shall or may be ordered as aforesaid by the said justice, and at each and every such August session, all actions, pleas, and other proceedings relative to any cause, civil or criminal, shall be continued over to the ensuing February session.

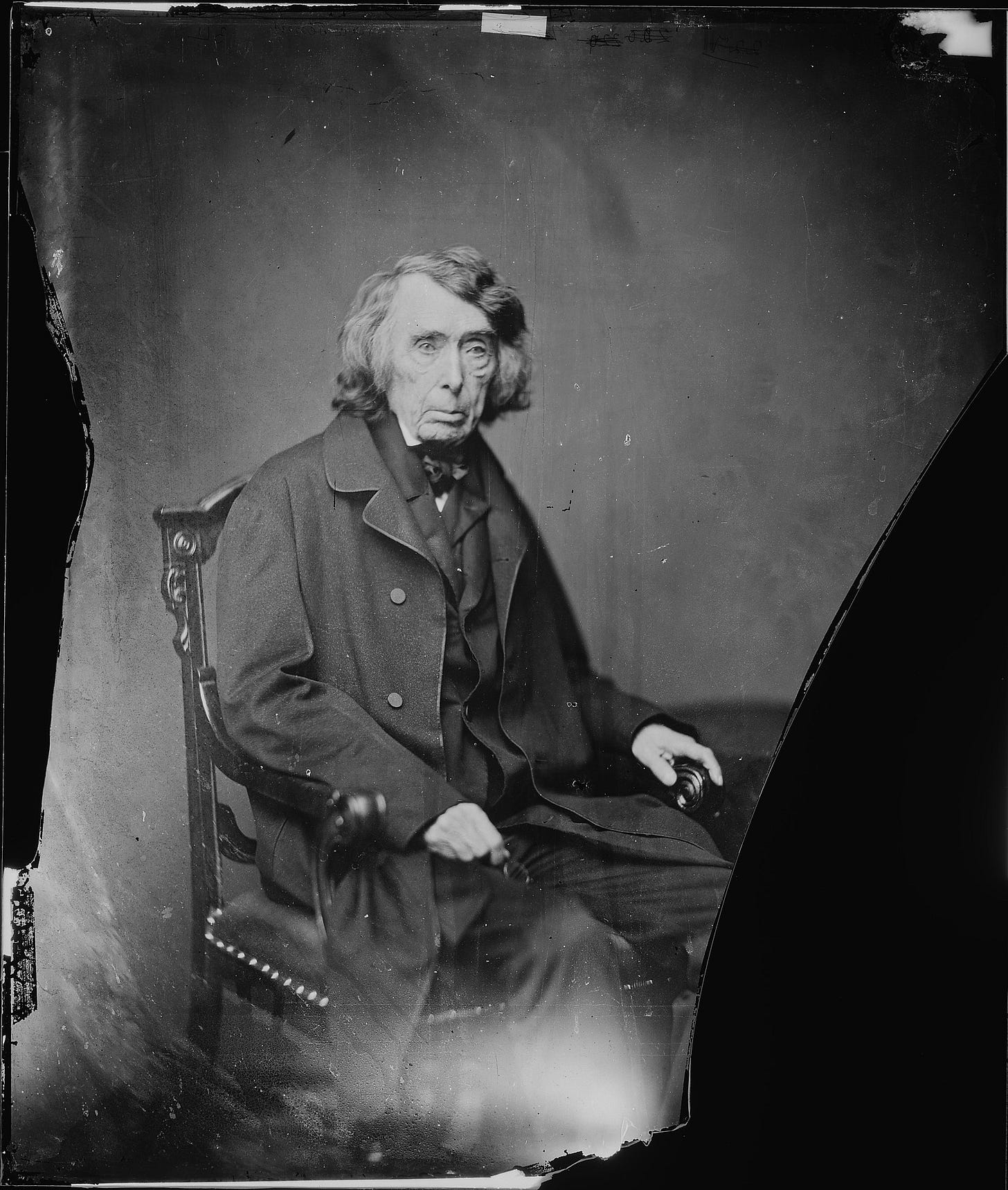

To tie threads together, the “Fourth Circuit formed by this act” comprised Maryland and Delaware, so Congress was deliberately singling out Associate Justice Samuel Chase (soon to be impeached, but not removed), who was the only current Justice to qualify. Indeed, presiding over the “rump Court” would remain the obligation of the Justice resident in the Fourth Circuit through the cessation of the practice in 1838—passing from Chase to Justice Gabriel Duvall in 1811, and from Duvall to Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney in 1836 (Taney, a Marylander, replaced John Marshall, a Virginian; so Philip Barbour, a Virginian, was appointed to fill Duvall’s Maryland seat).

And as Davies documents, it was Taney, in the 1836 and 1838 rump sessions, who provided the clearest evidence that the single-Justice sessions were, in fact, carried out on behalf of the full Court. In August 1836, Taney used the rump session to formally present and confirm his own credentials to ascend the bench (as was the tradition), something he did not do when the full Court met for the first time following his appointment the following January.1

And in August 1838, Taney heard oral argument and delivered an opinion respecting an order to show cause in a case (Ex parte Hennen) that the Court would eventually hear and resolve during its January 1839 Term—a move that, as Davies persuasively argues, made sense only if he viewed himself as acting as part of the full Court rather than as the Circuit Justice for the Fourth Circuit. (Davies’s article also reprints in full Taney’s unreported August 1838 opinion.)

Taney’s move in Hennen helped to draw public attention to the oddity of the Court’s rump August Term—which Congress disposed of in February 1839 with only vague allusions to “efficiency” by way of explanation. But the broader precedent was set: Congress’s control over the Court’s docket included the ability to designate a single Justice (indeed, a specific Justice) to at least resolve procedural and other case-management issues on behalf of the full Court. No one appears to have suggested, at any point along the way, that such a measure was unconstitutional—either in how much power it gave to a single Justice or in how specifically it exercised control over the Court’s workload. It’s a footnote to the broader history of the Federalist/Democratic-Republican battles of the early 1800s, but perhaps, given more recent events, an increasingly relevant one.

SCOTUS Trivia: In-Chambers Arguments

The argument in Hennen appears to be the only oral argument in the 37-year history of the rump Court. But it gives me a chance to flag another subtle (but important) shift in the current Court’s emergency applications practice. It’s likely familiar that such applications are directed to the individual justice with assigned responsibility for the geographic area from which the case arises. But whereas the norm today is for that “Circuit Justice” to refer any remotely divisive application to the full Court for consideration, it was far more common, as late as the 1970s, for Circuit Justices to rule in the first instance even in matters on which the full Court might be divided. This norm turned into a rule over the summer; prior to 1980, the Court formally adjourned when it rose for its summer recess, leaving the Circuit Justice as the arbiter.

To that end, it was also far more common, as late as the 1970s, for justices to hold “in-chambers” oral arguments on emergency applications—and to regularly write (brief) opinions respecting the disposition, whether they granted or denied the application for relief. Some of these arguments were literally “in chambers”; others were simply before a single justice in some other venue. But just as the norm of having circuit justices usually go first died out starting in 1980, so, too, did the practice of in-chambers arguments. According to the Supreme Court Practice treatise, “it appears that no Justice has heard oral argument on an application since 1980.”2 In-chambers opinions have also largely become moribund; the most recent example is more than nine years old.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue, featuring the June installment of “Karen’s Corner,” will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

Congress had changed the beginning of the full Court’s Term from February to January in 1826.

Although Supreme Court Practice doesn’t provide a citation, it appears that Justice Marshall held in-chambers argument on either May 5 or May 6, 1980 on the application for a stay in Blum v. Caldwell, 446 U.S. 1311 (Circuit Justice Marshall 1980). I am unaware of any subsequent in-chambers argument.

Your article reminded me of how Robert Caro outlined the legal strategy employed by Abe Fortas during Lyndon Johnson’s 1948 Senate campaign. As far as the Court’s role came into play, Fortas knew that Texas fell under the Fifth Circuit’s jurisdiction, and that Justice Hugo Black had oversight of its cases. Once the issue of an election, a state affair, and one already certified (a-hem) by the Texas Democratic party (by one vote), came before Justice Black, Mr. Fortas gambled that he would stop the lower district court’s permission to allow, in practical terms, the examination of voting roles in Alice.

If any of these machinations seem to have national parallels some 52 years later, I would not deny that such thoughts have crossed my mind as well.