2. Opinions and Orders

This week's issue offers an introduction to the two very different ways in which the Supreme Court resolves disputes, and why our attention tends to focus too much on one at the expense of the other

Welcome to the second installment of “One First,” a weekly newsletter about the Supreme Court. Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to some procedural or substantive feature of the Court’s workload or historical developments; and some Court-related trivia.

In addition to Monday’s free newsletter, each Thursday will feature bonus content for paid subscribers (last week’s was a brief introduction to three of my favorite crazy-but-obscure Supreme Court decisions). I hope you’ll continue to send feedback on what you like (and don’t like) about the newsletter, along with requests for topics to cover in future issues. And if you’re not already a subscriber, or are thinking about upgrading to a paid subscription, there’s no time like the present:

On the Docket

To outward appearances, it was a quiet week at the Court. No oral arguments were held; no opinions in argued cases were handed down (we’re still waiting for the first from the current Term). But appearances can be deceiving.

Saturday morning came the major New York Times story from Jo Becker and Jodi Kantor about behind-the-scenes efforts to influence (and the possible leak of the result and author of) the Court’s 2014 ruling in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., in which a 5-4 majority held that the Affordable Care Act’s mandate requiring insurers to cover contraception was unlawful, because it violated the Religious Freedom Restoration Act as applied to closely held (as opposed to publicly traded) secular corporations with religious objections to contraception. There’s a lot to say about the story (and ethics and recusal issues at the Court). We’ll save those for a future issue…

Inside the Court, although there were no opinions, the Justices handed down 87 orders last week, two of which provoked public dissents from three Justices. The first came on Monday, in Shoop v. Cunningham, in which Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch dissented from the Court’s refusal to take up the State of Ohio’s appeal in a post-conviction dispute in a capital (death penalty) case.

Thomas wrote a lengthy opinion on behalf of the three Justices, criticizing the appeals court (the Cincinnati-based Sixth Circuit) for not giving enough deference to the state court’s refusal to disqualify the jury foreperson in Cunningham’s criminal trial based upon some combination of having received prejudicial outside information during the trial and/or having an undisclosed relationship with the victims’ families. Because the Supreme Court voted to deny certiorari, the lower-court ruling (which ordered an evidentiary hearing into Cunningham’s claims) will stand.

The second ruling to provoke public dissents came on Thursday night, when the Court granted Alabama’s emergency application to vacate a decision by the (Atlanta-based) Eleventh Circuit that had blocked a scheduled execution. As the below screenshot captures, the majority offered no explanation for its decision to clear the way for the execution; and the three Justices who publicly dissented, Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson, offered no explanation for their disagreement. (The execution was later botched, and then postponed.)

In both cases, the decision of the Court came through an unsigned, unexplained order. And that’s the focus of this week’s newsletter: how to decipher the differences between and among the two ways in which the Supreme Court resolves disputes: opinions of the Court versus orders of the Court.

The One First Long Read: Opinions vs. Orders

For many (if not most) of us, the typical Supreme Court decision with which we’re familiar is an “opinion of the Court,” like in Dobbs. But as the above summary of the past week suggests, by volume, at least, the overwhelming majority of the Court’s output comes through orders—which, by tradition, are unsigned and (usually) unexplained, and which come with myriad additional mysteries. This week’s “Long Read” offers a descriptive introduction into the difference between “opinions of the Court” and “orders of the Court”; why the differences between them are often confusing; and why those differences have, in recent years, come to be increasingly important.

Opinions of the Court

There are two different contexts in which the Justices will hand down an “opinion of the Court.” The first is the familiar one: To resolve cases in which the Court granted certiorari (see last week’s introduction) and heard oral argument—cases resolved on the “merits docket.” Most (but not all) opinions of the Court in argued cases are “signed,” meaning that (1) an individual Justice is identified as the author of the majority or plurality opinion; and (2) every Justice’s vote is somehow accounted for. Consider this summary of the voting lineup in the Syllabus to the June 2022 decision in West Virginia v. EPA:

As you can see, we know from this summary not only that Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion, but also where/how every other Justice voted. Sometimes, the counting can be tricky, but there’s never a signed opinion in an argued case in which a Justice’s vote (or their non-participation) isn’t accounted for.

There can be un-signed opinions in argued cases, usually when the Court is acting very quickly, or is dismissing a case without reaching the merits after argument. These are denominated “per curiam” (i.e., for the Court), and that’s where things start getting tricky.

“Per curiam” opinions can come both in argued cases like these and in the other context in which the Court often hands down opinions of the Court—when there’s a majority opinion respecting a decision in a case that has not been argued. The two most common of these are (1) summary decisions at the certiorari stage (when the Court grants a petition and explains why it is reversing or vacating the decision below in the same ruling, usually to correct obvious errors); and (2) majority opinions relating to emergency orders (explaining why the Court is or is not granting an application for some form of emergency relief).

In both cases, the tradition, even when there’s a majority rationale, is that the author not be identified. Relatedly, whenever there is a “per curiam” opinion (in argued or non-argued cases), there is no requirement that every Justice publicly disclose their vote.

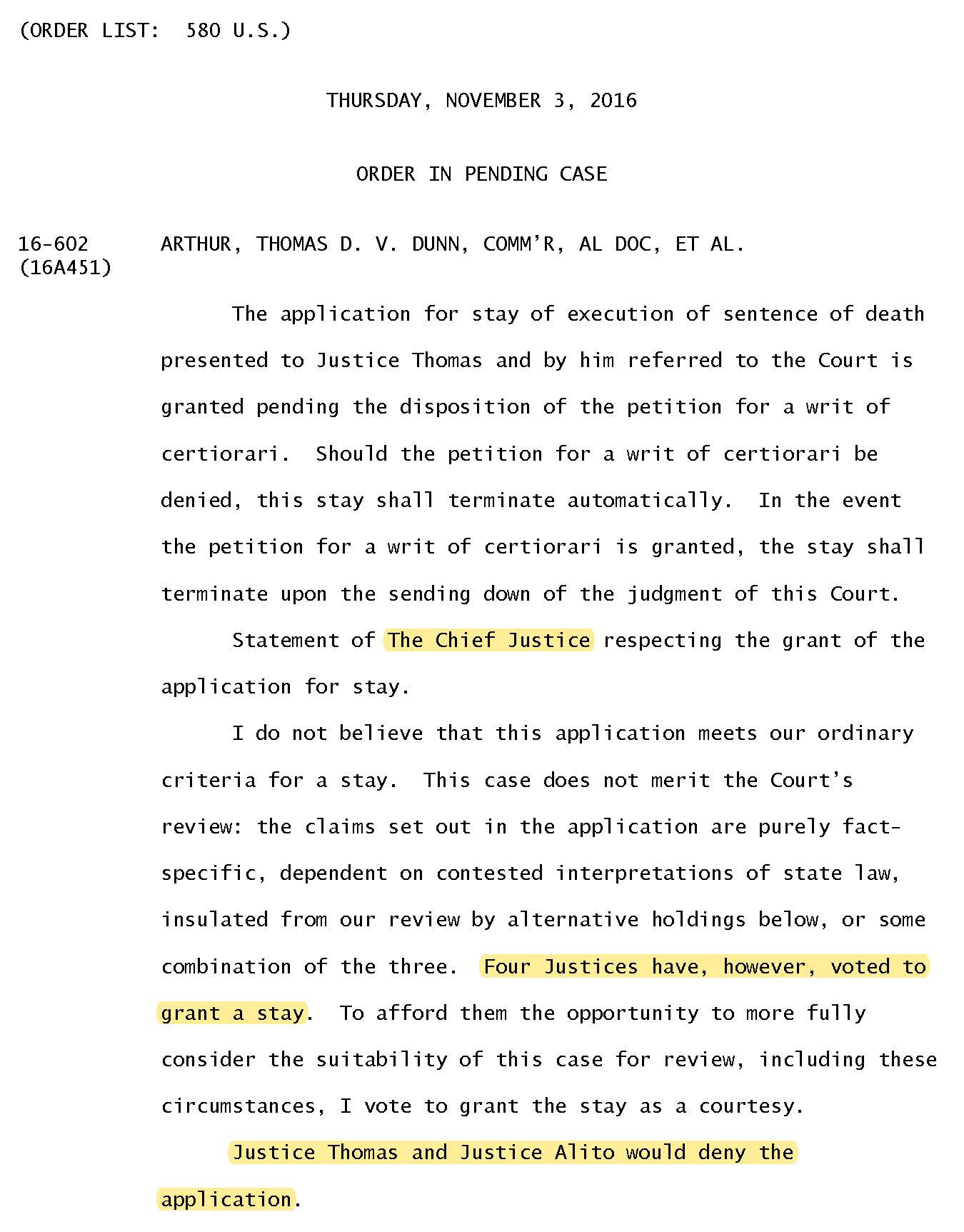

Thus, it is possible to have an “opinion of the Court” where we have no idea either which Justice wrote it or which Justices joined it. Only if a Justice publicly notes their concurrence or dissent can we be sure of how they voted. As a corollary, only if enough Justices note their votes can we be sure of how the full Court voted. At first blush, you might be surprised to learn that we can’t just assume that a Justice is in the majority unless they say otherwise. But we can’t. Here’s one of my favorite examples of a “stealth” dissent—a 2016 order by an eight-Justice Court granting a stay of execution:

In other words, Chief Justice Roberts said he was providing a fifth vote for the stay, from which we can reasonably conclude that the vote was 5-3. But only Justices Thomas and Alito publicly noted their dissent, so one dissenter is missing. (Almost certainly Justice Kennedy.) That stealth dissents can happen in any context other than a signed opinion of the Court complicates our next topic: When the Supreme Court ruling is an “order.”

Orders of the Court

You’ve already seen multiple examples of an “order” of the Court, i.e., any ruling of the Court that comes down without an opinion of the Court. By volume, these are the overwhelming majority of the Court’s dispositions of cases; most are denials of certiorari. But some, as in the above examples, are with respect to applications for emergency relief, when the Court is granting or denying an application to freeze or un-freeze some lower-court ruling or government action (like an execution).

As you’ve seen, the (strong) norms for all SCOTUS orders is that they are unsigned and explained, and that no vote count is revealed. As we’ll see in future issues, these norms can cause (and have caused) significant mischief as the Court in recent years has used orders more often and for broader types of emergency relief. For now, the key is just to understand that the vast majority of what the Supreme Court does is, for better or worse, both substantively and procedurally inscrutable—at least on the surface.

How Opinions vs. Orders Are Handed Down

Finally, and not helping matters, there’s the (not always predictable) way that the Supreme Court releases opinions and orders. Opinions in argued cases are the easiest; they’re handed down like clockwork at 10:00 a.m. on days the Court announces in advance. Although we never know which opinions are coming (until the last day of the Term, when the process of elimination allows us to figure it out), those who have the wherewithal can smash the refresh button on their browsers at the appointed hour when the Court has given word that a particular day is an opinion day.

Likewise, the Court hands down a regular “Order List” at 9:30 a.m. on the first work day after any week in which the Justices have held a “Conference” (we expect such a list later today). The Order List can include lots of different things, including procedural orders in pending cases (like giving parties additional time to argue); grants and denials of certiorari; summary rulings (including opinions of the Court) respecting a grant of certiorari; and, as with the three-Justice dissent in the Cunningham case described above, opinions relating to any of those orders.

But then the fun begins. Beyond regular opinion hand-downs and the regular Order List, there is the umbrella category that the Court calls “Miscellaneous Orders.” These can run the procedural and substantive gamut; they can come down at literally any time of the day (or night; here’s a 5-4 opinion of the Court that was handed down at 2:10 EDT one very late night in July 2020); and they can be (and have been) posted to any one of five different pages on the Supreme Court’s website, depending upon the specific form they take (which you’ll never know in advance).

Consider, for instance, President Trump’s pending application asking the Court to block the House Ways and Means Committee from receiving his taxes. A decision in that case could come at any time, and, depending on what it is, could appear on:

Opinions of the Court: If there’s an (unsigned) majority opinion explaining why the Court has granted or denied Trump’s application, it will appear on this page.

Opinions Relating to Orders: If there is no opinion of the Court, but at least one Justice writes a separate opinion either concurring in or dissenting from the disposition, it will appear on this page.

Orders of the Court: If there is no opinion of the Court and no separate opinion by any Justice, a ruling by the full Court will appear on this page.

In-Chambers Opinions: If Chief Justice Roberts, as Circuit Justice for the D.C. Circuit, resolves the matter on his own as Circuit Justice and writes an opinion, it will appear on this page.

The Case-Specific Docket: If Chief Justice Roberts resolves the matter on his own and denies relief without any explanation, it will appear only on this page.

This may seem like a small point; as soon as the decision comes down, members of the Supreme Court’s press corps will be alerted to it, and they’ll alert us. But the … complexities … of the different ways in which the Court could rule on the same application underscore the broader point: If you really know what you’re doing, you can find the Court’s ruling, but figuring out what (and where) it is often takes more than just a law degree.

Hence, the “Shadow Docket”

All of the above is why, in 2015, University of Chicago law professor Will Baude used the term “shadow docket” to refer to everything the Supreme Court does besides the opinions of the Court in argued cases—everything from unsigned opinions of the Court summarily reversing lower-court rulings to unexplained orders from individual Justices acting on their own. Baude meant the term descriptively, not pejoratively—as a reference to the obscurity of this large (and increasingly significant) percentage of the Court’s workload:

For what it’s worth, I think there is a lot more to critique about how the Court has used the shadow docket in recent years. The purpose of my forthcoming book is to introduce the shadow docket to a popular audience and put it in the context of the Court’s broader history so that readers can decide for themselves if the Court’s recent efforts have been a meaningful departure from prior practice (and, if so, whether they have been a troubling one).

Again, though, the key is that the overwhelming majority of what the Supreme Court actually does comes through unsigned and unexplained orders—and signed opinions in argued cases are actually the exception, and not the rule (there were a total of 58 during the October 2021 Term).

SCOTUS Trivia: The Demise of “Mr. Justice”

That was … a lot. So now for something different.

You’ve probably never heard of the Supreme Court’s November 1980 decision in Dennis v. Sparks. A technical dispute over when private defendants who allegedly conspired with state officials could be sued for violating the federal Constitution, the broader institutional significance of Dennis is that it was the first ruling to reflect an 8-1 decision the Justices had made three days earlier—to stop referring to each other, as they had for decades, as Mr. Justice, “my Brother,” or “the Brethren.”

The common assumption is that the Justices dropped these male-dominant references upon the confirmation of the Court’s first woman Justice, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, in September 1981. But the shift happened a full year earlier, thanks largely to Justice John Paul Stevens.

As the story goes, Stevens had participated in a moot court at the University of Notre Dame in 1979 in which he sat alongside Chief Judge Cornelia Kennedy of the Eastern District of Michigan, leading to more than a little awkwardness when advocates referred to Stevens as “Mr. Justice Stevens” and Kennedy as “Madame Justice Kennedy” (Kennedy asked why any salutation in front of “Justice” was necessary).

Stevens and Justice Potter Stewart soon proposed to their seven colleagues that they drop the male-dominant references to each other in their opinions and arguments, and, on November 14, 1980, the Justices voted 8-1 to do just that. (Justice Harry Blackmun, the lone dissenter, suggested that they wait to be joined by a female colleague, as they would 10 months later.) The decision in Dennis, three days later, was the first to reflect this change.

One male-dominant practice remains: To this day, when introduced at the lectern, advocates refer to the Chief Justice (all 17 of whom have been men) as “Mr. Chief Justice.”

I hope you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content, including monthly AMAs; sneak peeks (including excerpts from my forthcoming book on the shadow docket); and other surprises, please consider becoming one. This week’s bonus issue will have a Thanksgiving theme, in which my grandmother, Judith Vladeck, figures prominently:

Happy Monday, everyone. Have a great week!