17. Arlington, the Lees, and the "Officer Fiction"

A dispute between Robert E. Lee's family and the federal government over a Civil War-era tax has had outsized influence in shaping the modern rules for suing the government

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

The Court handed down a pair of opinions in argued cases on Tuesday. In the “original jurisdiction” case of Delaware v. Pennsylvania, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson (in her first majority opinion since joining the Court) held for a unanimous majority that Delaware could not in fact keep $250 million in unclaimed MoneyGram instruments just because MoneyGram is incorporated in the First State. Instead, the Federal Disposition Act applies, meaning that the abandoned instruments at issue can be claimed by the (different) states in which they were purchased.

And in Bittner v. United States, a 5-4 majority led by Justice Neil Gorsuch narrowed the penalty for failing to properly report foreign bank accounts under the Bank Secrecy Act, holding that the $10,000 penalty is only per report, not per account (so that a report that misstates the balances/existence of 27 different foreign accounts amounts to a single violation of the statute). As often happens in federal criminal cases turning solely on statutory interpretation, the decision produced an odd lineup, with Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Alito, Kavanaugh, and Jackson joining the majority; and Justices Thomas, Sotomayor, and Kagan joining Justice Barrett’s dissent.

The Court also wrapped up oral arguments for its February session, including the much-anticipated (and closely watched) arguments on Tuesday in the student loan cases (the standing issues in which I previewed in last week’s installment of the newsletter). And last Monday’s regular Order List included two grants of certiorari for next Term, the far higher-profile one of which is in the CFPB case (in which the Fifth Circuit effectively held that the way Congress funds the agency violates the Constitution).

Finally, on Thursday, the Court issued a request for additional briefing in Moore v. Harper (the independent state legislature case, which was argued back in the fall), in light of the North Carolina Supreme Court’s intervening decision to rehear its ruling in the case after the composition of that court changed. To make a long story short, the question on which the Court is seeking input is whether the grant of rehearing by the state’s highest court either formally or practically divests the U.S. Supreme Court of the power to resolve the dispute. Put another way, does the intervening state court action give the Justices a way to avoid a potentially major ruling in Moore. Those briefs are due two weeks from today at 2 p.m., although we won’t know what comes of them until the Court rules.

This week ought to be a bit quieter. At least as of now, there’s been no public indication that any opinions in argued cases are expected. And the Justices are not scheduled to hold a Conference this week; the next one isn’t until next Friday, March 17. Instead, all we expect is the Order List out of last Friday’s Conference, due later this morning at 9:30 ET.

The One First Long Read: Sovereign Immunity and the “Officer Fiction”

“Sovereign immunity,” the (contested) idea that the sovereign cannot be sued without its consent,1 is at the core of a dizzying array of doctrines that govern how government actions can (and can't) be challenged in court. Even though the text of the Constitution is silent on the subject, the Supreme Court has recognized since at least 1846 that the federal government is generally immune from civil suits to which it doesn’t consent. (State sovereign immunity is … another matter, which I’ll cover in a future installment—or four.)

Congress has, over time, waived a hefty chunk of the federal government’s sovereign immunity—authorizing suits under the Federal Tort Claims Act for a number of torts by federal officers acting within the scope of their employment; suits for contract and other monetary claims under the Tucker Act; and an array of non-monetary relief under section 702 of the Administrative Procedure Act. But (1) it didn’t have to do any of those things; and (2) there are still cases that those statutes don’t cover, such as damages suits arising out of violations of the Constitution. That’s where the “officer fiction” comes in. And to understand the fiction, we have to understand the canonical case articulating it—the facts of which are, well… read on.

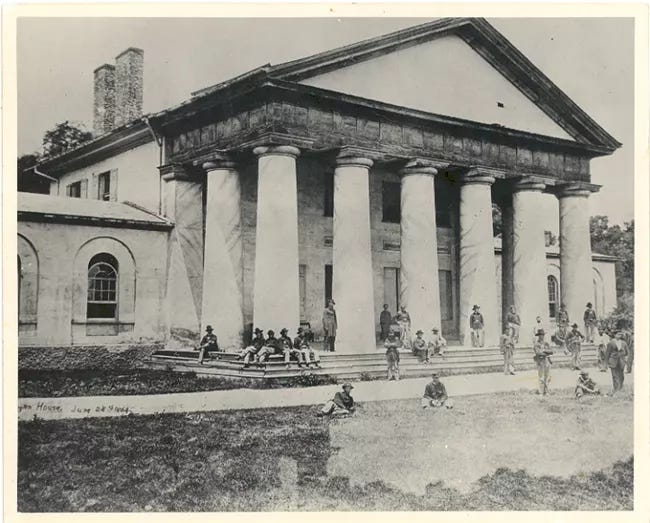

“Arlington” was a massive (1,100-acre) plantation on the west bank of the Potomac River, purchased in 1778 by John Parke Custis—son of Martha Washington and her (late) first husband, Daniel Parke Custis. When John died in 1802, he left the property to his son, George Washington Parke Custis (who John named after his step-father). The junior Custis set out to build a large, Greek Revival-style mansion as a monument and museum to his step-grandfather (and adopted father), George Washington, on land overlooking the new national capital named for him.2

The house was finally finished in 1818, and, when Congress retroceded the Virginia half of the District of Columbia to Virginia in 1846, it, too, became part of Virginia. George Washington Parke Custis died in 1857, at which point the plantation (including its now-sizeable population of enslaved people) passed to his only acknowledged daughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, known by that point as Mary Lee—having married a U.S. Army officer named Robert E. Lee in 1831.3

Although her husband was busy elsewhere, Mary Lee was apparently still living at Arlington as late as early May 1861, when she was urged to pack up her belongings and leave by a cousin who was serving as private secretary to General Winfield Scott, then the commanding general of the Union Army. Sure enough, just hours after Virginia voted to secede from the Union on May 23, Union troops crossed the Potomac and occupied Arlington (the strategic significance of which was plain for all to see). Mary, by that point, had fled to Richmond.

In June 1862, Congress passed a law (known as the “Doolittle Act,” after its sponsor, Wisconsin Senator James Rood Doolittle) that empowered federal agents to assess and collect taxes on confiscated property in “insurrectionary districts.” Although the statute was partly designed to raise revenue for the war, it was aimed just as much to punish Confederate VIPs like the Lees. If the taxes were not paid by the property owner, commissioners were authorized to sell the land.

Under the statute, a tax of $92.07 was assessed against Arlington in 1863. Mary, who was stuck in Richmond because of the fighting and was also in no medical condition to travel, asked her cousin Philip R. Fendall to appear and pay the bill. This was a remarkable concession to federal authority, or, at least, to the prospect that the Lees might one day be subjected to it again. But it was to no avail; when Fendall presented himself before federal commissioners in Alexandria, he was told that they would accept the tax only from Mary herself (even though nothing in the text of the statute clearly required the title holder to appear in person). Declaring the property in default, the tax commissioners put it up for sale. On January 11, 1864, the federal government bought the property—and promptly turned it into a national military cemetery, a purpose it has served ever since.

The Lees would spend 17 years after the war fighting to get Arlington back, including through multiple failed petitions to Congress. And after the “Compromise of 1877” seemed to augur a softening of hostility toward former Confederates, Robert and Mary’s son George Washington Custis Lee (known as Custis) decided to try the courts. Custis filed an “ejectment” action in Virginia state court, seeking to have the court physically remove those he claimed were in unlawful possession of Arlington—including Frederick Kaufman and Richard P. Strong, the civilian and military federal officers overseeing the Arlington property, respectively.

Because the validity of Kaufman’s and Strong’s “possession” of Arlington turned on whether the United States had validly acquired it, the federal government removed the case to federal court—where it urged dismissal on the ground that Custis Lee could not have sued the government directly, so that his suit should be barred by sovereign immunity. The lower courts sided with Lee, teeing up the government’s (and Kaufman’s and Strong’s) appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court also sided with Lee, albeit by a 5-4 vote. Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Miller agreed with the federal government that the Constitution protects the sovereign immunity of the United States, and thus bars suits against it without its consent. Indeed, Miller’s opinion remains today one of the most robust assertions of the federal government’s constitutional sovereign immunity. But that didn’t resolve the matter in dispute in Lee, Miller wrote, because suits against federal officers, even for actions undertaken in their official capacity as federal officers (no one suggested Kaufman and Strong had taken possession of Arlington in their personal capacities), were often another matter, especially where the underlying claim implicated the constitutional rights of the plaintiff (here, the due process and Takings Clause rights of the Lees), and where it could be shown that the officers themselves bore some personal responsibility for the claimed unlawfulness. In other words, Custis’s suit against Kaufman and Strong did not implicate the federal government’s sovereign immunity because of both the nature of the relief he sought (ejectment) and the legal violation he sought to remedy (a constitutional violation).

Justice Gray (joined by Chief Justice Waite and Justices Bradley and Woods) dissented, suggesting that the distinction on which the majority relied was one without a difference:

The sovereign is not liable to be sued in any judicial tribunal without its consent. The sovereign cannot hold property except by agents. To maintain an action for the recovery of possession of property held by the sovereign through its agents, not claiming any title or right in themselves, but only as the representatives of the sovereign and in its behalf, is to maintain an action to recover possession of the property against the sovereign; and to invade such possession of the agents, by execution or other judicial process, is to invade the possession of the sovereign, and to disregard the fundamental maxim that the sovereign cannot be sued.

Subsequent cases, though, have crystallized that very distinction (even as they have somewhat narrowed the scope of the fiction). Under what’s now loosely known as the “Larson-Malone” doctrine (after the Supreme Court’s decisions in Larson and Malone), as Professor Greg Sisk has explained in his helpful “Primer on the Doctrine of Federal Sovereign Immunity,”

a suit may be maintained directly against a governmental officer under two circumstances. First, if the officer allegedly acted outside of the authority conferred on his or her office by Congress, that is, beyond delegated statutory authority, then his or her conduct will be treated as individual in nature and will be neither attributed to the sovereign nor barred by sovereign immunity. Second, if the officer acted within the conferred statutory limits of the office, but his or her conduct allegedly offended a provision of the Constitution, then sovereign immunity will be lifted.

In other words, an officer can be sued without implicating sovereign immunity so long as they were acting ultra vires—either by exceeding the authority delegated to them by law, or by acting in violation of the Constitution. In those circumstances, they are liable in their “personal” capacity, even though the acts giving rise to the suit were undertaken in their capacity as a government officer.

To be sure, Lee wasn’t the first case to suggest a distinction between suing the federal government itself and suing its officers as a means of challenging the government’s conduct. But it was the first to fully grapple with the relationship between sovereign immunity and officer suits, and, thus, to first lean into the “officer fiction.” Lots of Federal Courts doctrines would follow, including the rise of official immunities (including qualified immunity) as defenses in cases in which officers were sued for damages and could not claim sovereign immunity. Suffice it to say, there’s lots more to say about the contours of those doctrines. For now, though, the key point is that all of these contemporary doctrines governing how suits challenging official action are brought in the federal courts have at their origins a remarkably pointed dispute that has a very personal story of Civil War-era enmity as its backdrop.

It’s certainly awkward, and not just for pedagogical purposes, to have so much significant doctrine (and so much of the flow of contemporary litigation challenging unlawful government action) flow from such a factually unique case—and from a broader legal principle that is routinely described as a “fiction.” But maybe it takes a fiction to beat a fiction. Or, as the authors of Hart and Wechsler’s The Federal Courts and the Federal System put it in their classically (maddeningly?) rhetorical style:

Is it a fiction that such suits against officers are not against the state even when they implicate important government interests? Or is the fiction that there ever existed a broad doctrine of sovereign immunity that, outside of a few specific areas, barred relief at the behest of individuals complaining of government illegality?

As for Arlington, it turned out that Custis Lee didn’t really want it back. Rather than force the federal government to disinter nearly 20,000 graves, abandon the fort that had been erected on the grounds, and otherwise clear the property, Custis sold the property “back” to the United States for $150,000. Congress quickly appropriated the funds, and Arlington was formally deeded over to the federal government on March 31, 1883.

This is where the history gets too strange for fiction: The federal officer who accepted the title was President Arthur’s Secretary of War, who in 1883 just happened to be Robert Todd Lincoln. Lincoln was not just President Lincoln's oldest son; he had been an eyewitness to Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox (and would be the last surviving eyewitness upon his 1926 death).

SCOTUS Trivia: Dates of Pre-1883 Supreme Court Decisions

As I hope to explain in detail in a future edition, for most of the Supreme Court’s first century, its decisions were not officially published, but were instead compiled by private reporters who sold the volumes for profit. (This is why Supreme Court citation forms through Volume 90 include a parenthetical for the name of the reporter, such as “5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803),” indicating that it was the first volume of William Cranch’s reports, and the fifth of the Supreme Court’s reports overall.)

Relatedly, it was only with Volume 108 of the (by-then official) U.S. Reports, in 1883, that the date of the decision was always included in the official reporter. What that means is that reference to the “official” reporter, or even to the version of the decision in commercial databases such as Lexis or Westlaw, would often note only the Term in which the case was decided—not the actual date of decision. Thus, cases would often be misdated in citations by as much as a year.

My favorite example of this is Mississippi v. Johnson, an effort by Mississippi to attack military reconstruction by suing the President directly in the Supreme Court. The statute Mississippi was challenging was enacted in March 1867 (and the decision rejecting Mississippi’s challenge was handed down on April 15, 1867). But the printed version of the opinion in Volume 71 of the U.S. Reports (Volume 4 of John William Wallace’s reports), or even the online version in Lexis or Westlaw, might lead you to conclude that the decision was handed down in “December 1866.” Such time-travel would be really impressive, even for the Supreme Court.

Fortunately, the Supreme Court itself has closed the historical gap. Thanks to a remarkable feat of research by Anne Ashmore from the Supreme Court Library, the Court has publicly posted a 168-page list of the dates of argument and decision for every published ruling from the Court’s inception through the end of Volume 107, i.e., May 7, 1883. That includes the decision in Lee, handed down on December 4, 1882—and published in Volume 106.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

Sovereign immunity was justified under pre-revolutionary English practice on the rather persuasive ground that the King ought not be liable before his own courts. But given that one of the Constitution’s central departures from that practice was the creation of a judiciary that was independent of the executive, it’s not exactly self-evident that sovereign immunity ought to survive the translation.

Custis had help: At least 57 enslaved people came with him to Arlington in 1802, and countless more were brought to the plantation over the years.

It appears clear that George Washington Parke Custis had at least one unacknowledged child, Maria Syphax, whose mother was one of the enslaved people at Arlington.

Prof. Vladek--Thanks for another illuminating analysis of a complex legal issue and history. I have one question. Following your link in Footnote 3 to https://www.nps.gov/arho/learn/historyculture/whose-land-claims-at-arlington-estate.htm, I found this quote:

"By 1669, colonizer John Alexander acquired 6,000 acres and willed it to the next generation. By 1778, John Parke Custis purchased 1,100 of these acres from Gerrard Alexander."

Either 1,100 or 11,000 acres is a serious farm, but I think that the latter-- ~17 sq. miles --would take far more than "at least 57 slaves".

Nicely written, Professor. Thank you. Particularly liked the tie-in to Robert Todd Lincoln at the end. A couple of refinements: John Parke Custis (known to his illustrious stepfather as "Jacky"), the sole surviving child of Daniel Parke Custis and Martha Dandridge Custis (later our first First Lady) was apparently not the sharpest knife in the drawer, at least not when it came to real estate deals. He had inherited a bundle from his natural father and used a good bit of that wealth to acquire Abingdon (now the site of Reagan National Airport - if you look hard, you'll find a historical marker in the parking garage), on an installment payment basis that was absurdly favorable to the seller. Jacky struggled the rest of his short life to make the payments. His stepfather (and Father of our Country) couldn't believe the lad's lack of business acumen. At the time he acquired Abingdon, Jacky also acquired the 1,100 acre adjoining parcel that became Arlington. Jacky died of disease in 1781 while serving on General Washington's staff. He died intestate leaving his affiars in a mess that wasn't straightened out until after his widow's (Eleanor) death in 1811, 30 years down the road (Eleanor deserves special mention for having gifted the world with 23 children, 7 with Jacky and 16 with her next husband).

George Washington Parke Custis (hereinafter "GWP"), General Robert E. Lee's eventual father-in-law, was less than a year old when his feckless father died. He was raised by George and Martha at Mount Vernon. He came into possession of Arlington on reaching the age of 21 in 1802, but this was more than 20 years after his father's death. Upon GWP's death in 1857, the property passed to GWP's eldest grandson, George Washington Custis Lee (who, like his better known father, also became a Confederate general officer), subject to a life estate in Mrs. Robert E. Lee. For all the association with Robert E. Lee, General Lee never had a direct ownership interest in the property. He did, however, serve as Executor of GWP's estate and directly managed it for the benefit of his wife and oldest son from the late 1850s up to the commencement of the Civil War.