11. The Leak Investigation and the Separation of Powers

The Supreme Court clearly *could* have done more to get to the bottom of the Dobbs leak. Whether it *should* have raises messier questions about the Court's relationship with the executive branch.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday morning, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court; a longer introduction to the Court’s history, current work, or key players; and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope that you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

On the Docket

What was looking like a quiet week at the Court (including the final three arguments of the January argument session) got noisy in a hurry on Thursday afternoon, when the Court released a report on the status of the investigation into the leak of Justice Alito’s draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. As you’ve no doubt heard by now, the investigation was unable to identify the person or persons responsible for the leak, and the report focuses largely on recapping the investigators’ efforts and making recommendations about increased document control measures that would, presumably, make it harder for a similar leak to recur in the future (never mind that it’s hard to close the barn door without knowing how it was opened).

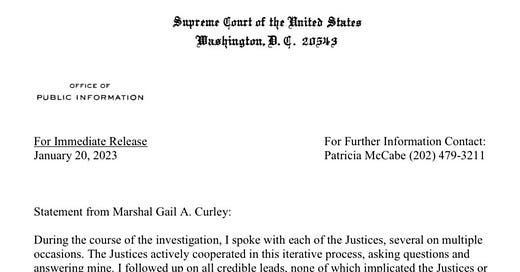

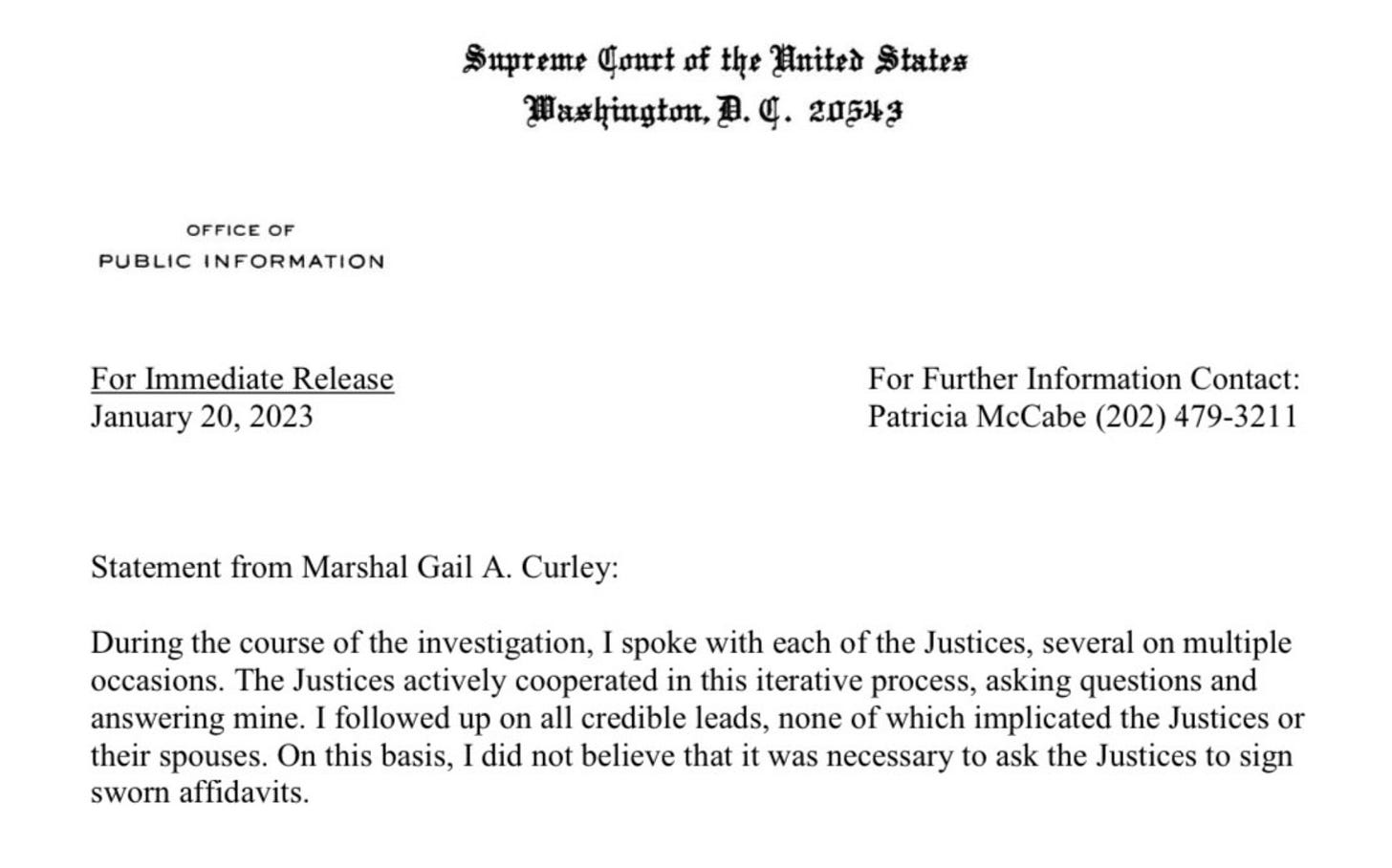

As released on Thursday, the report included no explicit suggestion that the Marshal of the Supreme Court, Gail Curley, had interviewed the Justices themselves or close family members. This omission prompted a firestorm all its own, leading Curley to issue a press release on Friday:

Given that the investigation is the subject of this week’s “Long Read,” I’ll end the recap here. Suffice it to say, the report was quite a big deal—as much for what it says about what the Court didn’t do as for what it says about what it did.

Meanwhile, in addition to a regular Order List from last Friday’s Conference at 9:30 ET this morning, we also expect something we haven’t seen all Term: an opinion of the Court! Returning to its pre-COVID protocol, the Justices will take the bench at 10:00 ET, and will formally hand down one or more opinions of the Court based upon reverse order of seniority of the Justice who wrote the majority opinion (so Justice Jackson would be first if she has one). These announcements will not be live-streamed (sigh), so those not in the courtroom (or the Court’s press room) will be left to refresh the hitherto-empty opinions page.

I’ve noted this before, but today marks exactly 16 weeks since the beginning of the October 2022 Term—or 112 days. The previous record for how deep the Court went into an October Term without an opinion of the Court was 65 days. Perhaps Thursday’s report is one of the reasons why the Justices are so far behind. And although the norm in years past has been for the first opinion (or two) to be in relatively less-important cases, we’ll cover them in next week’s issue one way or the other.

The One First Long Read: Investigating the Court

With apologies to those who came here looking for an in-depth discussion of the Black-Jackson Feud (the topic I had originally planned for this week as promised in last Thursday's bonus content about arguing before the Court by telephone),1 it would’ve been hard to justify not talking about the leak investigation report that the Court handed down Thursday afternoon.

The report is actually three different documents: An unsigned, two-page “Statement of the Court Concerning the Leak Investigation”; a one-page statement from Michael Chertoff (who was brought in to review the Marshal’s investigation); and a 20-page “Marshal’s Report,” by Gail Curley, the Marshal of the Supreme Court, recounting the efforts and results of her investigation into the leak. There is also apparently a confidential annex (“Annex A”) that was not made public, which includes more detailed operational and security recommendations for the Court going forward.

I’m not going to rehash these documents here; plenty of others already have in more detail. And yesterday’s New York Times included a lengthy piece by Jodi Kantor that provides even more detail and depth about how the Court attempted to investigate itself, as well as an excellent summary of the report itself. Instead, I want to ask (and try to answer) two questions: Could the Court have done more? And, if so, should it have?

Could the Court Have Done More?

The first question is the easier one. As lots of folks have already pointed out elsewhere, the Court’s investigation, at least as it has been publicly described, left more than a little to be desired—especially if the goal was an unconstrained, unabashed quest to actually find the leaker. Among other things:

It does not appear that anyone was given a polygraph test.

Although the Court obtained “call and text detail records and billing statements” for personal cell phones from a number of employees, there was apparently no attempt to recover any further data from those devices.

The interviews with the Justices were not under anything approaching the same circumstances as those with the Court’s (other) employees, and the Justices were not required to sign affidavits swearing to any of their statements.

There was apparently no effort to interview anyone outside of the Court, even voluntarily.

There is no suggestion in any of the three documents that other contemporaneous leaks from the Court (of which there were several) were considered in any way, let alone taken as relevant evidence.

And, although the report makes reference to various outside investigations and other personnel, there was quite clearly no effort to take advantage of investigative powers that, for example, the FBI could have wielded—including subpoenas and other coercive requests for information, whether from Court employees or others (the Marshal does not herself possess a subpoena power).

Simply put, if the only (or even primary) goal of the leak investigation was to identify the perpetrator(s) come hell or high water, this was a very strange way for the Court to have structured and pursued the investigation. Of course, that may not have been the only goal of the investigation, but therein lies the rub.

At least some of these constraints were necessarily intrinsic to the institution. The lack of subpoena power aside, there was never going to be a universe in which the Court would be fully able to investigate itself, especially in a context in which at least some suspicion has fallen on the Justices themselves—who are, let’s be clear, at the very top of the institution charged with the investigation. In his brilliant 2013 article in the Harvard Law Review, “The Leaky Leviathan: Why the Government Condemns and Condones Unlawful Disclosures of Information,” my friend and Columbia law professor David Pozen made this same point about leaks within the executive branch: “Forces within government sharply limit any President’s ability to invigorate apprehension efforts or otherwise deviate from the norm of broad-based leakiness. The likelihood of catching culprits is endogenous to the system.”

To be sure, there’s no comparable “norm of broad-based leakiness” in the judiciary. But there are other respects in which there’s a lot about the zeitgeist of the current Court and the hierarchical structure of the organization that parallels Dave’s thesis about the executive branch—and in which the obvious shortcomings of the Court’s investigation parallel the shortcomings of many (if not most) executive branch leak investigations, as well. (Yes, you should go read Dave’s article for more.) Simply put, the Court was going to have a hard enough time investigating itself even if the focus wasn’t on the Justices and their chambers. Insofar as it was, that made a comprehensive internal inquiry all-but impossible.

Should the Court Have Done More?

If we agree that there are obvious (and less-obvious) steps that the Court could have taken to pursue a more comprehensive investigation, the harder question is whether it should have taken those steps. Critically, given the formal and practical intrinsic limits, that would have almost certainly meant surrendering (at least some) control over the investigation to the executive branch, since it would likely have taken subpoenas and other forms of compulsory process that the Marshal lacked the power to issue, and investigators not directly answerable to the Justices, to get closer to the mark here.

The arguments for crossing that line are pretty obvious: The leak was an enormous deal; it damaged the Court in lots of ways both big and small; and, insofar as the leak was politically motivated (whether as an attempt to entrench the overrule-Roe majority into its views or to provoke a backlash that would perhaps shake one of its five votes loose), finding out which side it came from would have monumental significance for current and future debates about the Court as an institution (and, potentially, Court reform). And those are just the low-hanging fruit. What’s more, if one suspects that the leak came from a Justice (as some clearly do), crossing that line might not just seem necessary, but justified.

But I want to suggest, perhaps counterintuitively, that there are some pretty decent arguments for not crossing that line, even if they’re arguments that I’m not sure I, myself, ultimately find persuasive. As I’ve written in prior issues, one of the things that really sets the current Court apart from its predecessors is its self-confidence in its independence (if not insularity). This is a Court that is not in any way beholden to the legislature (the way that the Court, for a long time earlier in American history, was). It’s a Court that is not afraid of standing up to the executive branch (indeed, that may even relish doing so, at least right now). And it is a Court that, for better or worse, has arrogated to itself a remarkable amount of formal and practical decisionmaking authority in ways it’s not likely to (want to) relinquish. It is, in short, a Court that quite happily keeps its own company.

To take the investigation further would almost certainly have required the Justices to throw important features of that dynamic to the wind; to open the Court’s doors to the executive branch, and executive branch investigators, in ways that they’ve never been opened before. Such scrutiny might not only have had awkward and unintended direct consequences (including the potential of subjecting the Justices themselves to scrutiny the likes of which they haven’t faced since their confirmations); it could also have set a precedent for similar interventions in the future—perhaps in circumstances in which the outside assistance was less … welcome (and, from an institutional perspective, far more nefarious). The only modern precedent we have for anything like that was the Justice Department’s investigation of Justice Abe Fortas—an investigation that culminated in his 1969 resignation (we’ll spend some time with the Fortas episode in a future issue).

And even then, crossing that line might all have been for naught here—if, for instance, the “leak” were actually just a result of carelessness (a possibility that the Marshal’s Report quite interestingly does not dismiss); or if, as is true of at least some executive branch leak investigations, the leakers were ahead of the government’s technological ability to find them.

As anyone who has read prior installments of this newsletter will know, I’m a firm believer that the Court has become too insular, and that the political branches have become far too willing to leave the Court to its own devices, rather than engage in the healthy, interbranch dialogue that defined so much of the Court’s first 200 years. That said, my critiques have generally focused on how the Court operates as an institution. Crossing that line solely for the sake of allowing coercive investigative methods into the building isn’t as immediately obvious a sell for me, all the more so since leaking a draft opinion, by itself, is not a violation of any federal criminal statute.

Against that backdrop, it’s not hard to imagine that Chief Justice Roberts shared (and still shares) at least some of that same ambivalence, all the more so given his lack of similar support for more legislative intervention elsewhere. If anything, Roberts might also have believed that, as between catching the leaker and not catching the leaker, the latter might actually be a better result for the Court in the long run—not only because it keeps the executive branch out of the building, but also because of the harm the institution might have suffered if one of the two competing ideological narratives about the leak were in fact confirmed.

Ultimately, I believe that, all things being equal, a more rigorous investigation would have been “better,” regardless of the result it reached. But I don’t think that this view is remotely self-evident, and I can understand why the Chief Justice, among others, might have concluded otherwise.

SCOTUS Trivia: The Marshal of the Supreme Court

The topic of this week’s “Long Read” provides a rare excuse to talk a bit about the “Marshal of the Supreme Court” outside the context of social media conspiracy theories.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 authorized the President to appoint, with the advice and consent of the Senate, U.S. Marshals corresponding to each U.S. district court. And under that statute, the U.S. Marshal for the district in which the Supreme Court sat was also responsible for serving the Court. This created the slightly awkward arrangement in which an official firmly ensconced in the executive branch was directly responsible for all manner of Court business. (The Court had a separate employee who served as “crier,” who was responsible for formally convening and adjourning the Court’s sessions.)

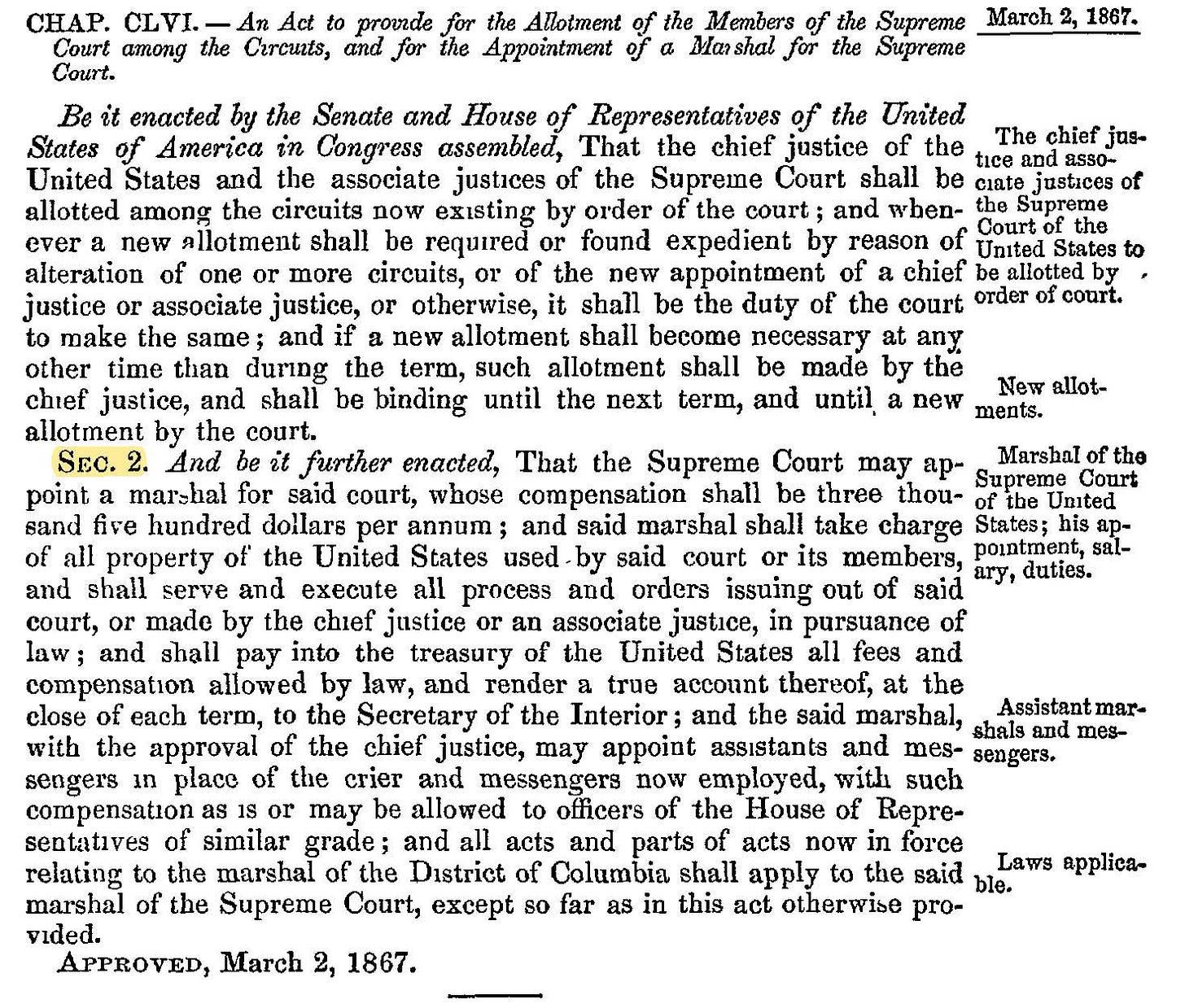

Perhaps with an eye toward the separation-of-powers issues, and perhaps just to take work off of the plate of the (busy) U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia, Congress in 1867 created the standalone position of Marshal of the Supreme Court, to be appointed not by the President, but by “the Supreme Court.”

Richard C. Parsons, an Ohio lawyer who would later serve in the House of Representatives, was appointed as the Court’s first Marshal (succeeded in 1872 by President Lincoln’s former personal secretary, John Nicolay). Gail Curley is the Court’s 11th (and second woman, after Pamela Talkin—who held the position from 2000–2020).

Indeed, since Parsons was appointed in 1867, there have been fewer Marshals (11) than there have been Chief Justices (12).

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue, which will be available only to paid subscribers, will drop Thursday morning at 8 ET.

Happy Monday, everyone! I hope you have a great week.

If you can’t wait for a future issue, you might be able to track down Dennis Hutchinson’s excellent article on the subject in the 1988 volume of the Supreme Court Review. It’s on JSTOR, but, alas, behind a paywall.

I know when this investigation started to spin up, there was some discussion of just how far (de facto as opposed to de jure) the Chief could go (or authorize the marshal to go) without having buy-in from his colleagues, especially when it came to the clerks. Probably hard to tell since the bulk of the report is from the Marshal, but were you able to glean anything regarding to what extent this was “The Chief Justice” versus “The Justices/The Court”? May be some inside baseball peculiar to the institution that’s hard to judge without being on the inside, but it would be interesting to know how much the justices collectively or certain justices in particular were able to steer the course of the investigation by taking steps like putting a foot down and saying “no I’m not ok with the unilateral polygraphing of my clerks.”

Polygraph? Perhaps the Justices and the Marshal are aware that polygraphs catch high-strung, nervous people, not guilty people.